Required Community Service in US High Schools

In the United States civic engagement has been a crucial component of society, whether it is through political activism or lending a helping hand to our fellow neighbors. In recent years, youth participation in volunteerism has fluctuated, resulting in a growing number of high schools requiring them to complete a certain number of hours of service in order to graduate. This increase is most notably seen in the late 80s and early 90s when “…[v]olunteer rates among youth ages 16-19 soared from 13.4 to 24.5 percent between 1989-2007”(Clemmitt, 79). There has been a range of reactions regarding the movement of mandatory participation in community service, from lawsuits to enthusiasm, which beckons the question, how has this requirement changed since the 90s and how has it affected their long-term outcomes as citizens? Since the 90s there has been an even greater push for service as a result of federal incentives, thus engaging more students into the community, creating civic minded individuals (which can be dependent on the structure of the mandatory program).

When researching high school graduation requirements of community service, there are several terms that ought to be clarified, as they may be confusing. Civic engagement is an overarching term and is defined as enhancing civic society through the combined use of “knowledge, skills, values and motivation” to achieve social change (NYTimes). This occurs through several means including: volunteerism, community service, and service-learning. Volunteerism is the genuine devotion of time to a cause without receiving compensation, whereas community service is similar on some level, but differs in the sense that some “volunteers” participate because they are required to through an institution, like a school. Service-Learning as defined by the former US Commissioner of Education, Harold Howe II is, “… an educational activity, program, or curriculum that seeks to promote student learning through experiences associated with volunteerism or community service…Service learning emerges from helping others and reflecting how you and they benefited from doing so” (Howe II, iv) These terms are often used interchangeably when discussing youth involvement in their communities. For the purposes of this research, the use of the terms service-learning and community service will be used interchangeably in a general sense of their definitions. The focus of this research will be required community service in US high schools since the 90s.

When engaging in the discourse of service-learning a key figure is philosopher John Dewey. Although he did not directly coin service-learning, he suggested that a significant instrument to education reform is experiencing the benefits of hands-on education that would contribute to social development (Conrad and Heiden, 1991). His words would bear more significance years later when the percentage of youth participation in volunteerism drops to 13.5 in 1989 (Clemmitt, 79). This drastically low percent heightened the urgency for youth civic engagement to increase. Thus individual schools began incorporating service-learning as a part of school curricula. The need for youth to be more civically engaged was acknowledged and solidified in 1990 when the federal government began promoting community service for all in the country while providing incentives for schools.

In the early 90s there were two significant pieces of federal legislature. The first was in 1990 when President Bush signed the National and Community Service Act which addressed the multiple facets of community service (Clemmitt, 79). This act provided $64 million in grants for community service programs like Serve America (now named Learn and Serve America) which works directly with students from the primary level through the tertiary level (ofm.wa.gov). The second piece was the National and Community Trust act of 1993 signed by President Clinton (Wutzdorff and Giles, 108). The law established the Corporation for National Service which promotes service through different organizations like Learn and Serve America (Wutzdorff and Giles, 108). These two efforts kick-started a movement toward greater youth participation in civic life. They allowed schools to pursue steps to receive federal funds for service-learning curricula. Recently, in 2009 President Obama has also encouraged volunteerism through federal legislature. In April of 2009 the Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act was passed, granting even more opportunities for service, considering the $1.49 billion budget (nationalservice.gov). These efforts further legitimized school-based volunteerism which has been steadily increasing.

Although these federal movements are impressive, it does not directly define its significance. What does youth disengagement mean? It is dangerous for youth to go through many years of schooling and not be able to realize the grander scheme of things. Life is more than grade in a class and certainly more than a test score; if students are not interested in anything outside of the realm of academics, we have will have potentially lost citizens that could contribute greatly to society. Sometimes students may not be connected to education whatsoever and may turn to other non-productive routes to fill up time. In order to avoid both of these scenarios, and any other of the like, providing a safe and engaging outlet like community service would not only benefit the youth, but the larger society as well. Some schools have decided to approach this issue of disengagement in a number of ways, which are not always welcomed.

The combination of the need for youth to be civically engaged as well as the opportunities provided by the federal government motivated high schools to incorporate community service/service-learning as a part of the curriculum, sometimes as a high school requirement. As of August 2011, only the state of Maryland and the District of Colombia has adopted community service as a graduation requirement. While this is relatively low, high school districts across 35 states incorporate some level of service learning(whether required community service or granting credit toward graduation) which fares pretty high compared to districts in seven states in 2001 (Education Commission of the States; servicelearning.org). As a result of an increasing number of schools that have a community service/service-learning component, in the years 2008-2010 33.7 percent of civic engagement in the US was school-based. Although many may see the social gains society and participants receive by being mandated to volunteer, there has been opposition to the high school graduation requirement.

Over the years, there has been an adverse reaction toward the graduation requirement of volunteering in the students’ communities. One such case is that of Steirer v. Bethlehem Area School District in 1993.

“The Third U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected the argument that a district’s 60- hour service requirement amounted to “involuntary servitude” banned under the 1 3th Amendment outlawing slavery. The amendment bans “forced labor through physical coercion,” not service that is “primarily designed for the students’ own benefit and education” by teaching them about the value of community work”(Clemmitt, 84).

This example, is obviously one of the most extreme reactions, but on some level understandable that one should pursue community service if they please. The Bethlehem case only further exemplifies the challenges schools face when trying to teach their students the value of community investment. One can assume what their immediate perspectives were upon fulfilling their requirement, which is a reflection of many youth: resentment and disdain. Researchers have attributed these attitudes to several factors like disorganization of service projects and imposing on the busy lives of the students. While mandating community service has been challenging in some respects, researchers have shown that it also inspires many students to do so as well.

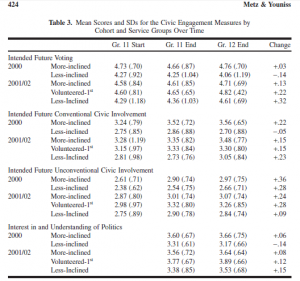

In a 2005 study researchers studied graduating high school seniors as the required service policy shifted. One group of students were in the graduating cohort that did not require community service (’00) while the 2 following cohorts (’01, ’02) were required to participate in community service. They looked even further into these groups and tracking the change in attitude toward civic engagement from those who were more or less inclined to volunteer. Prior to thecommencement of the study, the researchers Metz and Yuniss surveyed the students about their civic views and activity to establish a baseline. Over the years, they recorded the change in student answers to track any growth. The following table is an example of their findings.

Overall, the less- inclined group of students who were required to participate in community service demonstrated significant growth in their civic engagement. When asked about their likeliness of future voting, the less-inclined group which were required to volunteer showed a .32 standard deviation increase, unlike the less-inclined cohort that were not required. As you can see, they decreased .14 standard deviations. A clearer demonstration of this data is displayed in the graph below:

-

- Graphical display of decision to vote based on the groups of less and more inclined students who were and were not required to volunteer–Metz and Youniss

According to this research project, less-inclined students who are mandated to participate in community service, are generally benefited by furthering their desires to be civically engaged. Interestingly enough, one of the researchers Youniss participated in another relevant research project related to youth participation in community service and its effects in civic engagement. He and the small team of researchers discovered in 2007 that youth are more likely to vote (and participate in civic life through other manners) as a result to their exposure to community service in high school (Hart, Donnelly, Youniss, Atkins, 2007).

Although this research demonstrated some gains between these set of students there are other variables that need to be examined when determining why community service affects civic engagement. One must consider the factors that lead to successful implementation of community service requirements in high school. Jeffery Bennett of the University of Arizona conducted a study on urban high schools that had the graduation requirement suggested that the strength in the program determines whether or not it effectively promotes civic engagement. In his research he discovers that student opinion on community service and civic engagement was based upon the structure of the program. Mentors, better community relationships and a variety of service opportunities would have greatly influenced the views of the students. What is interesting is that Bennett explains that although that additional support would have been helpful, it would have also been limiting. For this study community service and service-learning are not interchangeable. I declare this because Bennett decides upon completing his research that requiring community service is limiting in the sense that it does not allow time for the students to process, to reflect upon their experiences. This only leaves them with an impression to volunteer some more versus looking at the larger picture and taking social action.

In sum, it is crucial to have youth participate in service learning/community service (mandatory or voluntary)/volunteerism that would expose them to becoming civically engaged. When youth are not involved, whether socially or politically, it puts our society at risk. We need a holistic view of education and citizenship in order to continue functioning as a society. It is therefor vital that we encourage our youth to become involved through federal incentives or even at the idea of personal growth. There is much to be learned outside of the classroom and much to gain as seen in the case studies outlined. There will be a continuous debate on whether or not community service should be required, but I think that we have to find ways to engage students to think beyond the walls of the classroom. Perhaps it will be through class trips, service-learning based curricula, or statewide required participation, whatever the means, we need to continue the efforts in order to maintain (as much as we can) a functioning society.

Bibliography:

Clemmitt, Marcia “Youth Volunteerism.” CQ Researcher by CQ Press, n.d.http://library.cqpress.com/cqresearcher/cqresrre2012012700.

Dávila, Alberto, and Marie T. Mora. “Civic Engagement and High School Academic Progress: An Analysis Using NELS Data, [Part I of An Assessment of Civic Engagement and Academic Progress.” InUniversity of Maryland, 2007.

“ECS Education Policy Issue Site: Service-Learning.” Education Commission of the States–Helping State Leaders Shape Education Policy. Web. <http://www.ecs.org/html/IssueSection.asp?issueid=109>.

Hart, Daniel, Thomas M Donnelly, James Youniss, and Robert Atkins. “High School Community Service as a Predictor of Adult Voting and Volunteering.” American Educational Research Journal 44, no. 1 (March 1, 2007): 197–219.

“Impacts and Outcomes of Service-Learning in K-12 Settings: Selected Resources.” National Service-Learning Clearinghouse. <http://www.servicelearning.org/impacts-and-outcomes-service-learning-k-12-settings-selected-resources>

Metz, Edward C., and James Youniss. “Longitudinal Gains in Civic Development Through School-Based Required Service.” Political Psychology 26, no. 3 (June 1, 2005): 413–437.

“NationalService.gov Our History and Legislation.” Corporation for National and Community Service. Web. <http://www.nationalservice.gov/about/role_impact/history.asp>.

Stanton, Timothy, Dwight Giles, and Nadinne I. Cruz.Service-learning: A Movement’s Pioneers Reflect on Its Origins, Practice, and Future. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1999. Print.

Schine, Joan G. Service Learning. Chicago: NSSE, 1997. Print.