“We know we are very fortunate. We all understood that these students are going to grow up here, stay here and be a permanent part of this community. Their success is key to our community’s success.”[i]

In October of 2010, I had the opportunity to intern at a local Hartford Public School. I was very eager to work with a recent Teach for America graduate at the time, and felt that I could bring a new perspective to his 6th grade classroom; as a product of the Hartford Public School system, I felt that I could truly relate to his students and serve as a valuable asset to the classroom. During my first few weeks at there, I found myself in a very difficult position: although I wanted to spend my time helping the students in the classroom with science projects and other assignments, I found myself being used mostly as a translator between the teacher and four [transfer] students who were in his homeroom. These students had recently moved to Hartford from Puerto Rico and were immediately enrolled into a Hartford school by their mother, who did not want to see them fall behind in their academics.

The Vice Principal of this school at the time explained that the school no longer had an official ELL program (English Language Learners) but rather, the children spent their fourth period in a class for students with developmental and behavioral problems. In this class, typically taught by a member of the school support staff, students received specialized attention with their classwork. Many times the class was taught by a bilingual staff-person; however, this was not always the case. I realized immediately that this arrangement was problematic – the children did not have behavioral nor developmental problems, they simply did not understand a word of English. Due to the experiences that these children and countless others face and the changing nature of ELL/Bilingual Education programs in Hartford Public Schools, both before and after the complaint with USDOE OCR was filed, we can see that Hartford has experienced a shift from a Spanish-language minority group to multiple language minority groups. Furthermore, albeit the Hartford Public Schools signed a resolution which provided a legal remedy to the immediate problems experienced by ELL [Bilingual] Students, the changes promised in the resolution have not yet been implemented in the district. Thus, the dual language concept to be implemented in HPS would not address ELL concerns for non-Spanish (and non-English) speaking minority groups.

Literature Review

Original Complaint: In April of 2007, the Center for Children’s Advocacy in Hartford filed a complaint with the United States Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights [USDOE OCR] claiming that “the city schools failed to adequately teach English language learners…”[ii] Reflecting on the experience of the Rivera children, it is clear to see that they were at an unfair disadvantage at their school. The district failed to meet the needs of every student, especially those who needed them most. Under Federal law, districts are required to provide sufficient support to students with limited mastery of the English language. In Hartford, the demographics of the schools are representative of the vast diversity of the City’s population. This led me to formulate this question: Why did Hartford ELL advocates pursue district compliance with federal law and does this fit with current broader Hartford Public School language policies?

The original complaint filed with USDOE OCR, was filed on behalf of Liberian, Somali-Bantu, and Spanish-speaking families with [what is referred to in the document as] Limited English-proficiency (LEP). The primary argument made by the Center for Children’s Advocacy in the complaint was that the “Hartford Public School district has not developed or implemented an adequate system for communicating with non-English speaking parents who are also non-Spanish-speaking.”[iii] As a result, the Center for Children’s Advocacy cited the Hartford Public School district as being in direct violation of “Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act which promises and the Equal Educational Opportunities Act of 1974 (EEOA).”[iv]

The Center for Children’s Advocacy cited that the district did not offer a sufficient bilingual education program for students with limited English proficiency. The Center reached out to numerous parents and community organizations including the Hartford Refugee Resettlement Group to make their case. This network of service providers would ultimately serve as a voice for Somali-Bantu youth and those students like them. The Center used valuable information given to them by the Resettlement group to show that many Somali-Bantu youth who had been given refugee status had limited-to-no previous formal education in their home countries. This would create important implications for the Hartford Public School District who would need to employ new strategies to reach these students.

The Center for Children’s Advocacy also found that the District had failed to provide parents with sufficient means of communication and that all communication from the schools were in English, which the Somali-Bantu families did not understand. In an October 2012 article featured in Education Week, titled, Schools Falter at Keeping ELL Families in the Loop, Lesli Maxwell outlines important information that all ELL districts should know about. In an interview with Peggy Nicholson, a representative with the Advocates for Children’s Services (an ally of the Southern Poverty Law Center), Ms. Nicholson explains that, “For these parents, it was an issue of not being able to be meaningful participants in decisions about their child’s education…”[v] The complaint filed in 2007 brought to light the changing composition of minority groups in Hartford. The shift went from a predominantly Spanish-speaking minority to a more diverse group, including for the first time ever, students such as Somali-Bantu youth and Liberian youth. The fact that these new families, including refugee families, were arriving in Hartford created a need to focus on the educational attainment of all students in enrolled in the Hartford Public School district.

The Center found that “by failing to establish an effective system for communicating with the Somali-Bantu students and their parents, the District was in violation of Title VI which reads:

No state shall deny equal educational opportunity to an individual on account of his or her race, color, sex or national origin, by… (f) the failure by an educational agency to take appropriate action to overcome the language barriers that impede equal participation by its students in instructional programs.

By this point, you may start to ask yourself: How do the teachers who are dealing with these students feel? According to a study released by Education Week, titled Teaching ELL Students, in 2006-07, the State of Connecticut certified a total of 836 teachers in Title III language instruction programs. Researchers found that the average number of ELL students per certified Title III teacher in Connecticut was 34. Interestingly, Connecticut was one of the many states that DID NOT require all prospective teachers to demonstrate competence in ELL instruction – the states that did require this for prospective teachers included Arizona, Florida, New York.

In Hartford, not only did teachers lack the materials and training to teach many ELL students, but some teachers went as far as to say: “The school system is not set up for this…teachers need more support.” This highlights a key problem about the ELL program in Hartford – if students don’t understand teachers, and teachers don’t understand the student population they are servicing, how can any learning or imparting of learning truly occur? Ultimately, the problem that ELL students in Hartford are experiencing is a multi-faceted dilemma that in order for the District to fully address, these Administrators must look deeper to see the many layers of the problem to fully address the concerns of ELL advocates.

Resolution to Complaint: On February 13, 2013, Dr. Christina Kishimoto, Superintendent of the Hartford Public School District filed a resolution agreement to OCR Complaint No. 01-07-1149 filed by the Center for Children’s Advocacy. In said resolution, the District outlined the steps that were to be employed to create an adequate program of learning and progress monitoring for ELL students. In the agreement, the District agreed to ensure approximately 45-60 minutes of daily bilingual support for ELL students.[vi] The District also promised to bring in more ESL teachers[vii] and bilingual school staff that could help the Hartford schools to reach its goal of providing ELL students with a meaningful education experience.

One of the major problems that I identified in the resolution agreement was listed under §4 of said agreement, titled “STAFFING”.

The Hartford Board of Education states that:

The District will use its best efforts to ensure that each school has enough qualified ESL – and bilingual-certified staff to provide the services described above. The District recognizes that “best efforts” includes promptly and actively recruiting qualified ESL – and bilingual certified staff when there are vacancies as well as assigning ESL – and bilingual-certified general education staff to provide ESL and bilingual services.

The problem lies in the wording of the claim: “when there are vacancies” – implies something very interesting that takes place in Hartford schools. When the district piloted its ESL programs, they searched for highly motivated, certified, well-educated individuals to fill positions as bilingual literacy coaches, mentors and teachers; when the ESL/Bilingual program was discontinued in Hartford, many of these educators trained for special populations stood on-board in their schools and transitioned into roles as literacy coaches, special education coaches and math coaches, according to one Hartford Public School district official who noted, “These instructors are too valuable a resource in our schools, so we had to find ways to keep them around.” Many of these teachers were on track to become tenured (if they were not already), had obtained advanced degrees and were members of teachers unions, for example. Given the fact that these individuals were in such high demand previously, it made sense to keep them around as they contributed greatly to the overall school and the community at large. Thus, although the resolution provided teachers with more professional development to help them to help the ELL students in their classrooms, they will never replace the teachers and coaches with advanced degrees in bilingual education who have a deeper understanding of the dual-language model and its implications.

Furthermore, the District promised to take on a more hands-on approach in identifying “new arrivals” (students who’d been in the U.S. for less than three years), long-term ELL Students (students who have undertaken an intensive ELL program and have not yet mastered proficiency in the English language even after the duration of their time in the program) and students with limited-to-no previous education in their home countries, such as the Somali-Bantu refugee children. The resolution also promised to provide more resources, such as translators for parents who would like to communicate with their child’s schools. This provided a remedy to using students as translators, which was seen as highly inappropriate and un-professional among those parents who needed a way to effectively communicate their thoughts and feelings to school officials. This challenged the notion of a neglectful school and district that did not previously care to communicate properly with these parents. It seemed that Hartford Public Schools wanted to use this document to thoroughly outline what it was going to take for the District to be in compliance with the regulation implementing Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, at 34 C.F.R. Section 100.3, which was the main violation cited in the OCR complaint.

Two-Way Feasibility Study: To have my readers fully understand the scope of what we are talking about in this paper, I would like to point out a few key terms. In a recent study which gauged the feasibility of implementation of a two-way language program in the 2014-2015 school year, (conducted by Achieve Hartford in partnership with the Hartford Board of Education), the term “English Language Learner” refers to any student who is “an active learner of the English language whose dominant language is other than English and whose proficiency in English is not sufficient to assure equal educational opportunity in the general education program…”[viii] The study details the steps that need to be made in order to fully implement Two-Way Language programs in Hartford Public Schools and implies that the road to a dual language program is long and toilsome, but not without its due rewards.

What was most striking in this study was that the list of ‘pros’ matched in length the list of ‘cons’ in the first few pages of the document. The lists were used to highlight what has and has not worked in the past in various Hartford Public Schools; in other words, the task of implementing a Two Way Language program has nearly as many benefits as it has limitations. On the “positives” list, the number one benefit listed was “Cognitive benefits to children: research has indicated children who grow up bilingual, bi-literate and multi-culturally competent surpass their non-bilingual peers in academic competencies and language skills.” [1] On the “challenges” list, the number one detriment listed was: “Requires more concentrated district support and resources.”[2]

The two-way feasibility study conducted for Hartford Schools also highlights the work that the Hartford Public School District is doing to create a multi-cultural consciousness among the many students they service. Many of these efforts include teaching students about different cultures through music, art and literature, such as Day of the Dead or Kwanzaa or learning about Japanese Internment Camps through Haiku written by Japanese-Americans – key concepts in cultural enrichment taught in schools, and taught in English. This is not conducive to a meaningful educational experience, particularly among students such as Somali-Bantu refugees, Liberian children or children of Dominican descent, for example, who may not have any formal educational experience prior to arriving in the United States.

Findings

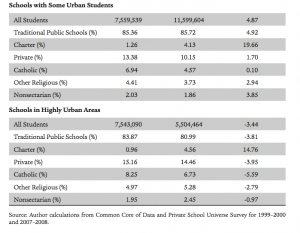

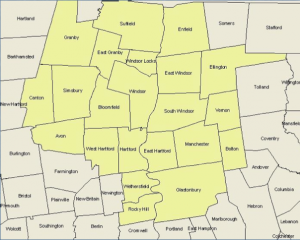

In the struggle to implement sufficient ELL programming in any schools, the multi-dimensioned effort needs to include everyone in the District who can help to provide a “meaningful experience” for these students, children who need them most. The effect can be felt from the top-down: the central office must find money to fund these specialized classes and specially trained teachers. In the schools, and specifically, in the classroom, teachers must find ways to not only help ELL students master both a new language, AND what is being taught the course. Also, important to note is that Spanish is spoken by the vast majority of English Language Learners, nationally. This is evident in the Hartford School District, where extensive programming for Spanish-speaking students had been (and in many respects continues to be) the main focus of the ESL programs in place in local schools.[ix]

In a recent article published in Education Week by Mary Ann Zehr, titled English-learners pose policy puzzle[x]. I was very interested to find the following statistical data, which placed this English-Language-Learning paradox in the vanguard of my mind for many weeks:

Only 23.6% of students who start the ninth grade in New York City as English-Language Learners graduate four years later, although, some continue their schooling and receive diplomas after that. The four year dropout rate for ELLs is 41.8%…The families of school-aged ELLs are consistently more socio-economically disadvantaged than those of their peers. ELL youths are half as likely to have a parent with a two or four year college degree and much more likely to live in a low-income household. While 2/3rds of ELL youths have a parent who holds a steady job, their parents typically earn much less than those of non-English-Language Learners.

This put the ELL paradox shows us that families who are not proficient in English will struggle more significantly than families who have English fluency. Families who have a proficiency in English are able to effectively communicate with their schools, albeit ELL families, in many cases, cannot. According to Federal Law, “school districts are required to provide adequate support to students with limited English proficiency so that they can meaningfully access a school’s curriculum.”[xi] When Somali-Bantu Refugees fled Somalia, not only were these “New Arrivals” experiencing a myriad of problems as newcomers to the United States, the schools were not helping ease their burden.

For this reason, the data leads me to believe that due to the experiences that these Somali-Bantu, Liberian and Spanish-speaking children and countless others face and the changing nature of ELL/Bilingual Education programs in Hartford Public Schools, both before and after the complaint with USDOE OCR was filed, a shift has occurred in Hartford. The City has experienced a shift from a Spanish-language minority group to multiple language minority groups. Furthermore, albeit the Hartford Public Schools signed a resolution which provided a legal remedy to the immediate problems experienced by ELL [Bilingual] Students, the changes promised in the resolution have not yet been implemented in the district. Thus, I believe that the dual language concept to be implemented in Hartford would not address ELL concerns for non-Spanish (and non-English) speaking minority groups.. It seems that although the Somali-Bantu refugee families, Liberian families and other ELL families are slowly integrating into the City of Hartford, the vast majority of families in the ELL program are still Spanish-speaking. The District would need to further identify and monitor the progress of “New Arrivals” to see which strategies and best practices work for these families. Naturally, these families would have to ask questions and reach out to find resources such as the Hartford Refugee Resettlement Group which would in turn help get these families adjust to the United States. They would also need to take full advantage of the translator sources which are outlined in the resolution agreement, to truly be involved in ensuring that their child gets a fair education. Hartford Public Schools has a very good outline of how the resolution to the ELL paradox should look, but the fact of the matter is that until these reforms are implemented, the Hartford School District is STILL in violation of Civil Rights law. The only way these reforms could ever be effective is if they are implemented immediately and in the time frame that was promised in the resolution agreement.

***

Bibliography:

Center for Children’s Advocacy. “Complaint to the US Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, Concerning Limited-English Proficient Learners in the Hartford Public Schools,” April 11, 2007.

DeLaTorre, Vanessa. “Hartford Courant: After Federal Probe, Hartford Schools Agree To Improve Services For ‘English Language Learners,” March 22, 2013.

Hartford Public Schools. Two-Way Language Program Feasibility Study, January 3, 2013.

Lesli Maxwell, “Schools Falter at Keeping ELL Families in the Loop,” Education Week, October 2, 2012.

US Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights. “Hartford Board of Education (District) OCR Complaint No. 01-07-1149 Resolution Agreement,” February 13, 2013.

Mary Ann Zehr, “English-Learners pose policy puzzle,” Education Week, December 31, 2008.

[1] Hartford Public Schools, Two-Way Language, 2013.

[2] Hartford Public Schools, Two-Way Language, 2013.

[i] Maxwell, 2013

[ii] De La Torre, After Federal Probe, Hartford Schools Agree To Improve Services For ‘English Language Learners

[iii] CCA Complaint, USDOE OCR, 2013

[iv] CCA Complaint, USDOE OCR, 2013

[v] Maxwell, 2012

[vi] Hartford Public Schools, Resolution Agreement, 2013

[vii] English Language Learners (ELLs) in Hartford are placed in an English-as-a-Second Language (ESL) program.

[viii] Hartford Public Schools, Two-Way Language

[ix] These schools such as Moylan, McDonough and Parkville School are all in neighborhoods with a very high Black and Latino population. (HPS State of the Schools Address, 2013)

[x] Zehr, English-Learners pose policy puzzle.

[xi] De La Torre, Federal Probe, 2013