West Hartford Science Walking Tour: Elizabeth Park/Morley School District

Roger Sperry once lived at 39 Robin Road.

Roger Sperry with Nobel Prize

Roger Wolcott Sperry was born August 20, 1913 to Francis Bushnell and Florence Kraemer Sperry. His father died when he was 11 and he moved with his mother and brother to the Elmwood section of West Hartford. His mother became the assistant to the principal at Hall High School which Dr. Sperry would attend. In his autobiography he notes that he collected and raised large American moths in grade school, that he ran a trap line and collected live wild pets during junior high school years and that he was a three-letter man in varsity athletics in high school and college (baseball, basketball, and track).

He attended Oberlin College on a 4 year Amos C. Miller Scholarship originally intending to go into coaching. He received an AB in English in 1935. But he had become interested in Psychology, however, after a course in Introduction to Psychology with Professor Raymond Stetson, and so he stayed on 2 years at Oberlin to earn an MA in Psychology, under Professor Stetson and then an additional third at Oberlin to prepare for a switch to Zoology for Ph.D. work under Professor Paul A. Weiss at the University of Chicago. After receiving the Ph.D. at Chicago in 1941, he did a year of postdoctoral research as a National Research Council Fellow at Harvard University under Professor Karl S. Lashley.

He was a Biology research fellow at Harvard University, at Yerkes Laboratories of Primate Biology (1942-46); Assistant professor, Department of Anatomy, University of Chicago (1946-52); Associate professor of psychology, University of Chicago (1952-53); Section Chief, Neurological Diseases and Blindness, National Institutes of Health (1952-53); Hixon professor of psychobiology, California Institute of Technology (1954-1994). He received numerous awards besides the Nobel, including being Elected American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1963), the Distinguished Scientific Contribution Award, American Psychological Association (1971); Honorary Doctor of Science degree, Cambridge University (1972); Ralph Gerard Award of the Society of Neurosciences (1979); and the American Academy of Achievement Golden Plate Award (1980)

He married Norma Gay Deupree, December 28, 1949. They had one son, Glenn Michael (Tad), born October 13, 1953 and one daughter, Janeth Hope, born August 18, 1963. He notes in his autobiography that through middle life he continued evening and weekend diversionary activities including sculpture, ceramics, figure drawing, sports, American folk dance, boating, fishing, snorkeling, water colors, and collecting unusual fossils – among which he had a contender for the world’s 3rd largest ammonite.

He described his work as occurring in four “turnarounds” which were: 1. Nerve regeneration & chemo-affinity studies; 2. Studies involving equi-potentiality; 3. Split-brain studies; and 4. Consciousness and values.

Sperry studied optic nerve regeneration and developed the chemoaffinity hypothesis. The chemoaffinity hypothesis stated that axons, the long fiber-like part of neurons, connect to their target cells through special chemical markers. That challenged the previously accepted resonance principle of neuronal connection.

In 1981 he won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for his discoveries concerning the functional specialization of the cerebral hemispheres.” He is the only person with a degree in Psychology to have won this prize

In a series of important studies he was able to demonstrate the differences in the functioning between the left and right hemispheres of the brain. Using people who had had the corpus callosum (the fiber tract that connects the two hemispheres) severed to help treat seizure disorder, he would present information to either the right or the left visual field. He demonstrated, among other things, that for most right-handed people the majority of language functions are mediated by the left hemisphere of the brain. When information was presented to the right visual field (left brain), the person could name the object, however when presented to the left visual field (right brain) they could not. Fascinatingly, however, despite saying they saw nothing, they could draw the object with their left hand.

Summing up his split-brain studies he wrote: “When the brain is whole, the unified consciousness of the left and right hemispheres adds up to more than the individual properties of the separate hemispheres.”

In the final phase, he wrote about human values. In his paper “Science and the Problem of Values” he states “the trends toward disaster in today’s world stem mainly from the fact that while man has been acquiring new, almost godlike, powers of control over nature , he has continued to wield these same powers with a relatively shortsighted, most ungodlike set of values.” These writings led to the development of the Declaration of Human Responsibilities by a group of distinguished scientists from around the world. The document is being considered by the United Nations as the step following the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Human Rights.

He died in 1994 of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig’s disease). You can see a short documentary on Sperry here

and a discussion of his split-brain work by his student Michael Gazzaniga here with some original footage.

The neuroscience building at Oberlin is named after him.

“Before brains there was no color or sound in the universe, nor was there any flavor or aroma and probably little sense and no feeling or emotion.”—Roger Sperry

Continue up Robin Road and turn right on Fern St. In two blocks you will see the elementary school named for Edward Morley on your right.

Continue on Fern St. to Prospect Avenue.

On the NW corner (what is now 777 Prospect) is where Yung Wing’s house once stood. You can learn more about him by using the Cedar Hill Cemetery information-dial (860) 760-9979 and press #21, or by watching this video from the West Hartford Historical Society.

On the NW corner (what is now 777 Prospect) is where Yung Wing’s house once stood. You can learn more about him by using the Cedar Hill Cemetery information-dial (860) 760-9979 and press #21, or by watching this video from the West Hartford Historical Society.

Yung Wing was born in 1828 in China and died in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1912. As a child in China his father sent him to a missionary school. At this school he met a minister from Connecticut, S.R. Brown, who brought Yung Wing back with him in 1847. He attended the Monson Academy in Massachusetts and, in 1854, graduated from Yale University, becoming the first Chinese student to graduate from a university in the United States. He obtained U.S. citizenship at this time. Yung Wing wanted to improve engineering and infrastructure in China. With the help of funding from the Chinese government and the establishment of the 1868 Burlingame Treaty, which allowed Chinese residents to have rights in the United States, he founded The Chinese Education Mission.

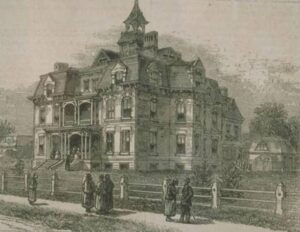

The Mission on Collins Street in Hartford

In 1872, 30 students arrived in Hartford, Connecticut, where they stayed with host families, were immersed in American culture, and attended local public schools, including Hartford Public High School. These students then went on to attend many prestigious U.S. universities. The plan was for them to return to China after their education and 15 years in the country. The educational Mission’s main office was on Collins Street in Hartford.

Home of Yung Wing and Mary Kellogg on the corner of Fern and Prospect

Yung Wing met Mary Kellogg from Avon who had become involved in helping to educate some of the students. They married on February 24, 1875 and they had two children. They lived for a time in a mansion on the corner of Fern Street and Prospect Avenue. Mary Kellogg became Yung Wing’s assistant and was involved in the running of the Mission. Sadly, she died in 1996 of what was then called Bright’s disease but is now known as acute glomerular nephritis. She was 35 years old and their sons were 10 and 7 at the time of her death.

The Mission ended when when the first prospective group of students to Annapolis and West Point were refused entrance. This represented a breech on the part of the United States of the Bulingame Treaty. As a result, the Chinese government withdrew support for the Mission and ordered the students and Yung to return to China. The students returned home in 1881, and Yung Wing returned to China. Despite the closing of the school, students who returned to China became educators, engineers, and physicians. However, as discrimination and bigotry grew in the United States, The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, one of the first laws restricting immigration into the United States, was passed. The United States revoked Yung Wing’s citizenship, and all remaining students were forced to return to China.

In the summer of 1898, a coup by the Empress Dowager Cixi reacted to modernization reforms, and the leaders of the reforms were arrested and executed. Yung Wing fled to British Hong Kong from Shanghai.

Yung returned to America in 1902 to see his younger son graduate from Yale and remained in the country with no legal status, living with his sons and dying at his home in Hartford in 1912. He is buried at Cedar Hill Cemetery in Section 10, Lot 6.

“The race prejudice against the Chinese was so rampant and rank that not only my application for the students to gain entrance to Annapolis and West Point was treated with cold indifference and scornful hauteur, but the Burlingame Treaty of 1868 was, without the least provocation, and contrary to all diplomatic precedents and common decency, trampled underfoot unceremoniously and wantonly, and set aside as though no such treaty had ever existed, in order to make way for those acts of congressional discrimination against Chinese immigration which were pressed for immediate enactment.”–Yung Wing

Hartford Courant, January 30, 1906, Page 1 details some of the discrimination he encountered

You can learn more here:

Yung Wing’s Dream: The Chinese Educational Mission, 1872-1881

and here: