We will begin in the parking lot of the Institute of Living just to your right as you enter from Retreat Avenue.

Founded in 1822, Institute of Living (IOL), The Retreat, was one of the first mental health centers in the United States, and the first hospital of any kind in Connecticut. The Institute of Living was founded on the premise of “Moral Treatment.” This approach was based on ideas of humane care and the realization that mental disorders were illnesses. The approach moved away from the use of restraints and moved toward a therapeutic approach. The original grounds included a swimming pool, golf course, and fleet of cars that people could take out for drives in the country. However, they did use the practice of electro-convulsive therapy (ECT) in ways that today would be considered controversial or inhumane.

You can read the account of Dr. Marsha Linehan and her treatment at the IOL in the 1960’s here in a New York Times article. The IOL still uses ECT but there have been many technological advances and it can be the only effective treatment in some cases of severe depression.

You can read the account of Dr. Marsha Linehan and her treatment at the IOL in the 1960’s here in a New York Times article. The IOL still uses ECT but there have been many technological advances and it can be the only effective treatment in some cases of severe depression.

The first Director was Eli Todd. HIs sister Eunice committed suicide after many years of depression and many attempts at treatment. This led him to the belief that depression was a disease that should be treated medically. He remained the director until 1833. You can learn more about him here.

The first Director was Eli Todd. HIs sister Eunice committed suicide after many years of depression and many attempts at treatment. This led him to the belief that depression was a disease that should be treated medically. He remained the director until 1833. You can learn more about him here.

In 1994 the Institute of Living and Hartford HealthCare merged, which allowed the IOL to accept individuals with public health care coverage. Today they are particularly known for their treatment of anxiety disorders, obsessive-convulsive disorder, and hoarding; Eli’s Retreat which still serves as a short-term group home; the schizophrenia rehabilitation program; the Grace Webb school; and for the research facility, the Olin Neuropsychiatric Research Center. Dr. David Tolin from the Anxiety Disorders Research Center appeared on the television programs The OCD Project, and Hoarders. The Professionals Program is designed for people with substance abuse or other issues who are working full-time and at one time had a specialization in treatment of clergy. This lead to a controversy when the Catholic Church claimed that they returned some priests with pedophilia to their parishes based on recommendations from staff at the IOL. The IOL countered that they were misled and that information was withheld from them. There is an article on this controversy here.

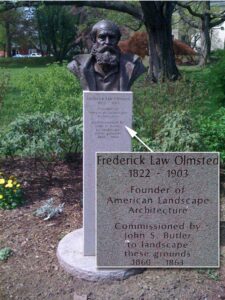

Take note of the remarkable trees and Frederick Law Olmstead and Jacob Weidenmann landscape architecture that was re-designed in the 1860s. Olmstead specifically designed the grounds to be restful and beneficial to mental health. You can learn more about Olmstead and the original design of the IOL here. Numerous signs on the grounds of the Institute represent rare species, many dating back to the 1860s and likely planted by Olmstead. You can take a tour of notable trees using this guide. In particular note the Champion Trees: the Sweet Gum (5), Gingko (7), Burr Oak (11), Pecan (19), and Japanese Zelkova (20).

Take note of the remarkable trees and Frederick Law Olmstead and Jacob Weidenmann landscape architecture that was re-designed in the 1860s. Olmstead specifically designed the grounds to be restful and beneficial to mental health. You can learn more about Olmstead and the original design of the IOL here. Numerous signs on the grounds of the Institute represent rare species, many dating back to the 1860s and likely planted by Olmstead. You can take a tour of notable trees using this guide. In particular note the Champion Trees: the Sweet Gum (5), Gingko (7), Burr Oak (11), Pecan (19), and Japanese Zelkova (20).

Photo taken from https://instituteofliving.org/about-us/frederick-law-olmsted

As we walk from the parking lot to the Burlingame Building we will see a bust of Olmstead. We will also see the Kentucky CoffeeTree (1), European Cutleaf Beech (2), and Yellow Bird Cucumber Magnolia (3).

We will now walk to the Burlingame Building (number 3 on this map). You can learn more about the Burlingame Building and the history of psychosurgeries at the IOL here.

Surgeries were performed on the sixth floor, postop was on the fifth floor, and they provided vocational and recreational rehabilitation, including home economics, accounting, and commercial art on the fourth floor. There was room for 37 guests, as they were called, who had been operated on. A Hartford Courant article from 1949 notes that the program stressed the individual vocational and hobby interests of each person.

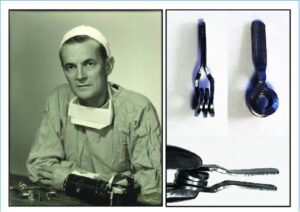

William Beecher Scoville established the Department of Neurosurgery here in 1939. William Beecher Scoville was a descendent of Harriet Beecher Stowe. He was born in Philadelphia in 1905 to Samuel and Katherine Gallaudet (Trumbull) Scoville. His mother was a descendant of Thomas Gallaudet. He attended Loomis School, received his undergraduate degree at Yale University and his medical degree at the University of Pennsylvania. He established the first neurosurgery department at Hartford Hospital in 1939. His first wife was Emily Learned Scoville and they had three children that they raised at 334 North Steele Road in West Hartford, Barrett, Alison, and Peter. In 1941 he developed the first neurosurgery residency program in Connecticut. His students referred to him as “Wild Bill.” ‘Bill drove fast, lived hard and operated where angels feared to tread,” said Dr. David Crombie, former chief of surgery at Hartford Hospital who met Scoville in the early 1960s as an intern at the hospital and became friends with his son. Scoville’s wife had schizophrenia and this may have played a role in his desire to find surgical options for treating mental illnesses. In the book written by his grandson, Luke Dittrick, Dittrick speculates that Dr. Scoville may have actually performed surgery on his wife, Emily Learned Scoville. In addition to the surgery on Mr. Molaison, Dr. Scoville is known for a coiled aneurysm clip that he invented. His second marriage was to Helene Deniau Scoville, with whom he had two children Sophie and William. Dr. Scoville’s brother was Rev. Gordon Scoville, the founding pastor of Westminster Presbyterian Church in West Hartford. Dr. Scoville had a life-long interest in cars and was known for driving his red Jaguar or motorcycle on Steele Road and tinkering with cars in his spare time. He was an early proponent for motorcycle helmets but never wore one himself. Scoville was killed in 1984, at the age of 78, when he backed up his car on the highway to get to an exit he had missed.

William Beecher Scoville established the Department of Neurosurgery here in 1939. William Beecher Scoville was a descendent of Harriet Beecher Stowe. He was born in Philadelphia in 1905 to Samuel and Katherine Gallaudet (Trumbull) Scoville. His mother was a descendant of Thomas Gallaudet. He attended Loomis School, received his undergraduate degree at Yale University and his medical degree at the University of Pennsylvania. He established the first neurosurgery department at Hartford Hospital in 1939. His first wife was Emily Learned Scoville and they had three children that they raised at 334 North Steele Road in West Hartford, Barrett, Alison, and Peter. In 1941 he developed the first neurosurgery residency program in Connecticut. His students referred to him as “Wild Bill.” ‘Bill drove fast, lived hard and operated where angels feared to tread,” said Dr. David Crombie, former chief of surgery at Hartford Hospital who met Scoville in the early 1960s as an intern at the hospital and became friends with his son. Scoville’s wife had schizophrenia and this may have played a role in his desire to find surgical options for treating mental illnesses. In the book written by his grandson, Luke Dittrick, Dittrick speculates that Dr. Scoville may have actually performed surgery on his wife, Emily Learned Scoville. In addition to the surgery on Mr. Molaison, Dr. Scoville is known for a coiled aneurysm clip that he invented. His second marriage was to Helene Deniau Scoville, with whom he had two children Sophie and William. Dr. Scoville’s brother was Rev. Gordon Scoville, the founding pastor of Westminster Presbyterian Church in West Hartford. Dr. Scoville had a life-long interest in cars and was known for driving his red Jaguar or motorcycle on Steele Road and tinkering with cars in his spare time. He was an early proponent for motorcycle helmets but never wore one himself. Scoville was killed in 1984, at the age of 78, when he backed up his car on the highway to get to an exit he had missed.

Now let’s turn to the surgery performed at Hartford Hospital on Henry Molaison by William Scoville on August 24, 1953.

Mr. Henry Molaison (known to the world as HM) was experiencing severe epileptic seizures. Mr. Molaison had his first appointment with Dr. Scoville around 1943. He was admitted several times to Hartford Hospital for pneumoencephalograms that were normal and EEG studies that only showed scattered activity not a single focus. Dr. Scoville suggested surgery. Dr. Scoville had performed similar surgeries for people with psychiatric disorders but not for people with seizure disorder, and the results of his surgeries were mixed. They were mostly performed on women who were confined to state hospitals in Connecticut and diagnosed with schizophrenia, although a few also had epilepsy. Unexpectedly, the surgery designed to treat the psychosis seemed to make the epilepsy better.

Mr. Henry Molaison (known to the world as HM) was experiencing severe epileptic seizures. Mr. Molaison had his first appointment with Dr. Scoville around 1943. He was admitted several times to Hartford Hospital for pneumoencephalograms that were normal and EEG studies that only showed scattered activity not a single focus. Dr. Scoville suggested surgery. Dr. Scoville had performed similar surgeries for people with psychiatric disorders but not for people with seizure disorder, and the results of his surgeries were mixed. They were mostly performed on women who were confined to state hospitals in Connecticut and diagnosed with schizophrenia, although a few also had epilepsy. Unexpectedly, the surgery designed to treat the psychosis seemed to make the epilepsy better.

In 1886 the first surgery was done to treat seizures by Victor Horsley in London. The area of the brain that was causing the seizure was removed. A part of the brain would be stimulated electrically to determine where the seizure was coming from and then that focus would be removed. This work was greatly improved by the cortical localization studies of Harvey Cushing at Johns Hopkins in 1908. In 1928 Wilder Penfield at the Montreal Neurological Institute developed the temporal lobectomy to remove a part of the right or left temporal lobe to control seizures. Penfield concluded from his research on brain mapping that temporal lobe seizures originated in the amygdala and hippocampus.

At age 27 Mr. Molaison agreed to have surgery done in the hopes of having some relief from the seizures. Before the surgery he was given a series of psychological and cognitive tests by clinical psychologist Dr. Liselotte Fischer at Hartford Hospital. Unfortunately he experienced several absence seizures during the testing so it is unclear how accurate the testing was. Although he was given many EEGs, a specific focus for his seizures was not able to be identified. This led Scoville to decide to do a more radical surgery then had been done previously. In Mr. Molaison’s chart Dr. Scoville admitted him for “new operation of bilateral resection of medial surface of temporal lobe, including uncus, amygdala, and hippocampal gyrus following recent temporal lobe operations done for psychomotor epilepsy” which he described as a “frankly experimental operation” (Scoville & Milner, 1957).

Then Dr. Scoville used a technique called resection that involved drilling a hole in the skull and then guiding an instrument into the brain and applying a fine suction to extract small pieces of brain at a time. Scoville drilled two holes in Henry’s skull, each an inch-and-a-half in diameter and five inches apart and he used these holes as the entranceway to Henry’s brain. He operated first on one side, and then the other. He inserted a brain spatula, or a retractor, to lift up the frontal lobe on the side where he was operating. And when he did that, he could then see into the tip of the temporal lobe. Scoville extracted the uncus, the front half of the hippocampus, some of the entorhinal cortex, the perirhinal cortex, and most of the parahippocampal cortex, and most of the amygdala on both sides of the brain. At the time these regions were known collectively as Papez circuit and believed to be involved in emotion.

Following the operation, Henry’s seizures were greatly reduced. However, he now experienced a severe anterograde amnesia. Dr. Scoville noted the operation “resulted in no marked physiologic or behavioural changes, with the one exception of a very grave, recent memory loss, so severe as to prevent the patient from remembering the locations of the rooms in which he lives, the names of his close associates, or even the way to toilet or urinal” (Scoville, 1954). According to Dr. Suzanne Corkin who worked with him: If you talked to him in the afternoon and said, “Have you had lunch?,” he would say, “I don’t know” or “I guess so,” but he would not remember what he had had. And if you asked, “What was your last meal?,” he wouldn’t know what it was.

Here is a transcript of a recorded conversation with Dr. Corkin:

“What do you do during a typical day?”

“See, that’s tough–what I don’t….I don’t remember things.”

“Do you know what you did yesterday?”

“No, I don’t.”

“How about this morning?”

“I don’t even remember that.”

“Could you tell me what you had for lunch today?”

“I don’t know, tell you the truth. I’m not—”

“What do you think you’ll do tomorrow?”

“Whatever’s beneficial” he said in his friendly, direct way.

“Good answer.” I said. “Have we ever met before, you and I?”

“Yes, I think we have.”

“Where?”

“Well, in high school”

“In high school?”

“Yes.”

“What high school?”

“In East Hartford.”

“Have we ever met any place besides high school?”

Henry paused. “To tell you the truth, I can’t–no. I don’t think so.”

“At the time of our interview, I had been working with Henry for 30 years. I first met him in 1962, when I was a graduate student. We had not met in high school as Henry firmly believed.”

We will listen to this conversation with Mr. Molaison and Dr. Corkin here. on an episode of Fresh Air.

Audio Player

You can hear more of Mr. Molaison from this episode of Weekend Edition.

Audio Player

He lost some of his memories from before the surgery, called retrograde amnesia, but it was surprising that he retained most of them. He knew his parents, facts about the world, how to talk, read, and write. Dr. Corkin notes “He could tell us about – you know, he knew where he was born, his father’s family came from Thibodaux, Louisiana, his mother’s came from Ireland. He talked about the towns in Hartford where he lived, and about his specific neighbors. He knew the schools he attended, some of his classmates’ names and, you know, the kinds of things he did for fun. So he had quite a lot of memories, but none of them were unique episodes.”

His IQ actually improved (perhaps because he no longer had seizures). Because of HM, researchers realized that there were multiple memory systems and that memories for personal events (episodic memory) involved different brain regions and cognitive processes than memories for facts and general knowledge (semantic memory).

He could also hold information in his short-term or working memory. So if given a list of numbers to recall he could repeat them back accurately. For example, if you gave him a phone number he would remember it for as long as it was in his short-term memory, but as soon as he was distracted with something else, he would forget it. It was because of him and this finding that support was gained for the understanding that we have two different memory processes: short-term and long-term.

Henry was also able to do kinds of memory we refer to as implicit or procedural. He was able to learn to do motor tasks like a mirror-drawing task, despite not remembering doing it before. This task involves looking in a mirror and trying to trace a figure while seeing your hand in the mirror. He improved on this task with practice. Because he could do these things he taught us that they do not rely on the hippocampus.

His memory was initially assessed by Brenda Milner in 1955, but then Suzanne Corkin began to work with him for her dissertation.

. Suzanne Corkin (née Hammond) was born at Hartford Hospital and was an only child. Dr. Corkin grew up in West Hartford, directly across the street from William Scoville, at 333 North Steele Rd, and was best friends with his daughter, Alison Scoville Dittrich. The two went to school together from third grade until college and stayed very close after that. Dr. Corkin went to the Oxford School in West Hartford. She went to college at Smith College and then received her PhD from McGill University. While there, she read an article about Henry Molaison and his memory deficits after psychosurgery and was intrigued. Shortly thereafter, her dissertation advisor, Brenda Milner, asked if she would like to work with him. Her dissertation was entitled “Somesthetic function after focal cerebral damage” which examined Mr. Molaison’s sense of touch. In 1964 she began working at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the lab of Hans-Lukas Teuber. When he died, she became the director of the lab. She devoted her career to working with Mr. Molaison and to studying how human memory works and the brain substrates of memory in a variety of populations. She was an early user of functional imaging like MRI and fMRI to help understand how memory works. She published over 150 research articles and was author or co-author of 10 books. She received a MERIT award from the National Institutes of Health and the Baltes Distinguished Research Achievement Award from the American Psychological Association, Division on Aging. She also became a committed advocate for increasing women in science, giving talks on the topic, and received the Brain and Cognitive Sciences Undergraduate Advising Award at MIT. After her death, a group of former students published this tribute to her.

. Suzanne Corkin (née Hammond) was born at Hartford Hospital and was an only child. Dr. Corkin grew up in West Hartford, directly across the street from William Scoville, at 333 North Steele Rd, and was best friends with his daughter, Alison Scoville Dittrich. The two went to school together from third grade until college and stayed very close after that. Dr. Corkin went to the Oxford School in West Hartford. She went to college at Smith College and then received her PhD from McGill University. While there, she read an article about Henry Molaison and his memory deficits after psychosurgery and was intrigued. Shortly thereafter, her dissertation advisor, Brenda Milner, asked if she would like to work with him. Her dissertation was entitled “Somesthetic function after focal cerebral damage” which examined Mr. Molaison’s sense of touch. In 1964 she began working at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the lab of Hans-Lukas Teuber. When he died, she became the director of the lab. She devoted her career to working with Mr. Molaison and to studying how human memory works and the brain substrates of memory in a variety of populations. She was an early user of functional imaging like MRI and fMRI to help understand how memory works. She published over 150 research articles and was author or co-author of 10 books. She received a MERIT award from the National Institutes of Health and the Baltes Distinguished Research Achievement Award from the American Psychological Association, Division on Aging. She also became a committed advocate for increasing women in science, giving talks on the topic, and received the Brain and Cognitive Sciences Undergraduate Advising Award at MIT. After her death, a group of former students published this tribute to her.

We were fortunate to have Dr. Corkin speak at Trinity College. You can watch the full talk here “The Amnesic Patient HM: A Half Century of Learning About Memory.” Here is a clip where she talks about whether Mr. Molaison has a sense of self.

Short Corkin Clip

After her death, Dr. Scoville’s grandson, Luke Dittrich wrote a book Patient H.M.: A Story of Memory, Madness, and Family Secrets. In it he claimed that Dr. Corkin tried to hide the existence of a lesion in the orbitofrontal lobe and that she shredded data to cover errors. This was refuted in a letter to the New York Times signed by over 200 scientists, and in the published In Defense of Suzanne Corkin. In fact, she had published data that she claimed suggested an orbitofrontal lesion in 1983 (Eichenbaum et al., 1983).

We will now head back to Retreat Avenue. In 2016 The Ayers Neuroscience Institute was formed with neurosurgery at 100 Retreat Ave. This is where awake craniotomies are currently performed. Current treatments for epilepsy include medications, diet, behavioral health care, as well as surgical procedures like laser ablation, surgical resection, neurostimulation, vagus nerve stimulation, and deep brain stimulation.

Continue down Retreat Ave until it ends at Maple Ave. Turn left on Maple Ave, bearing right on Wyllys. Take an immediate right on Congress Street.

2 Congress Street was a home of Mr. Molaison when he was a teen. His family likely was renting a few rooms in the house.

2 Congress Street was a home of Mr. Molaison when he was a teen. His family likely was renting a few rooms in the house.

Above is his draft registration card showing his address at 2 Congress Street in Hartford.

Mr. Molaison was born on February 26, 1926 in Manchester, CT. As a child he began to have absence seizures. His mother attributed the onset of seizures to a bicycle accident he had when he was ten, but there was also a family history of epilepsy on his father’s side. On his fifteenth birthday he experienced his first tonic-clonic grand mal seizure. After that his seizures made it difficult for him to participate in social activities, to drive, or to finish school. He started at Willimantic High School but dropped out. He then enrolled at East Hartford High but did not partake in any extracurricular activities besides Science Club.

Mr. Molaison was born on February 26, 1926 in Manchester, CT. As a child he began to have absence seizures. His mother attributed the onset of seizures to a bicycle accident he had when he was ten, but there was also a family history of epilepsy on his father’s side. On his fifteenth birthday he experienced his first tonic-clonic grand mal seizure. After that his seizures made it difficult for him to participate in social activities, to drive, or to finish school. He started at Willimantic High School but dropped out. He then enrolled at East Hartford High but did not partake in any extracurricular activities besides Science Club.

Attitudes about epilepsy were mostly negative at that time and he was often singled out by teachers and administrators because of his disability. In 1947, at 21, he graduated from East Hartford High but the superintendent would not allow him to participate in the ceremony because of concerns that he would have a seizure.

After graduation he had various jobs, including at the Underwood Typewriter Company on Arbor Street in Hartford (where Real Art Ways currently is). He took large doses of anti-seizure medications.

After graduation he had various jobs, including at the Underwood Typewriter Company on Arbor Street in Hartford (where Real Art Ways currently is). He took large doses of anti-seizure medications.

After the surgery he lived at 63 Crescent Drive in East Hartford and he could accurately draw the floor plan of that house. He had been very close to his parents and was upset each time he was reminded they had died, but then they would soon slowly come back to life in his mind. For a while, Henry made a habit of carrying around a little scrap of paper reminding him that his father was dead.

After the surgery he lived at 63 Crescent Drive in East Hartford and he could accurately draw the floor plan of that house. He had been very close to his parents and was upset each time he was reminded they had died, but then they would soon slowly come back to life in his mind. For a while, Henry made a habit of carrying around a little scrap of paper reminding him that his father was dead.

He died December 2, 2008. He is buried in Hillside Cemetery at 162 East Roberts Street in East Hartford. As you enter the cemetery stay to the right and his gravestone will be on your left in Section A.

“Right now, I am wondering if I have done or said anything amiss,” Henry once told a researcher. “You see, at this moment everything looks clear to me, but what happened just before, that’s what worries me. It’s like waking from a dream I just don’t remember.”

On December 4, 2008 the New York Times ran this obituary of HM.

After he died his brain was sliced via livestream and logged 400,000 viewers. Jacobo Annese et al. published high resolution photos and a 3-D reconstruction in Nature in 2014. The slices have been digitized and can be viewed on this website patienthm.org. During the silent feed, Annese placed little Post-it notes on the slicer, giving viewers a feeling of what it was like to be in the lab, such as “Playing the White Album now.”

From Annese et al. (2014): The fixed specimen was photographed after removal of the leptomeninges. Evidence of the surgical lesions in the temporal lobes is highlighted by white geometric contours (a, b). A mark produced by the oxidation of one of the surgical clips inserted by Scoville is visible on the parahippocampal gyrus of the right hemisphere (black arrow). (c) encloses a lesion in the orbitofrontal gyrus that affects the cortex and WM. Marked cerebellar atrophy is consistent with H.M.’s long-term treatment with phenytoin.

From Annese et al. (2014): The fixed specimen was photographed after removal of the leptomeninges. Evidence of the surgical lesions in the temporal lobes is highlighted by white geometric contours (a, b). A mark produced by the oxidation of one of the surgical clips inserted by Scoville is visible on the parahippocampal gyrus of the right hemisphere (black arrow). (c) encloses a lesion in the orbitofrontal gyrus that affects the cortex and WM. Marked cerebellar atrophy is consistent with H.M.’s long-term treatment with phenytoin.

Of note: White matter lesions, frontal lobe lesion, cerebellar atrophy that all could contribute to observed symptoms

A final quote from Dr. Suzanne Corkin:

“Henry Molaison was much more than a collection of test scores and brain images. He was a pleasant, engaging, docile man with a keen sense of humor, who knew that he had a poor memory and accepted his fate. There was a man behind the initials, and a life behind the data. Henry often told me that he hoped that research into his condition would help others live better lives. He would have been proud to know how much his tragedy has benefited science and medicine.”

We invite anyone from the community to add to this tour, or to add their own pin to our History Pin collection here.

To share this page, you can use this QR code:

For future tours:

Myths, Minds, Medicine: Two Centuries of Mental Health Care exhibit (not currently open). This exhibit located on the second floor of the Commons Building reviews the past 200 years of treatment for people with mental illness. The exhibit also looks at current treatments including a look at research on brain chemistry and a human brain on display.

Article from the Hartford Courant:

References:

Annese, J., Schenker-Ahmed, N., Bartsch, H. et al. Postmortem examination of patient H.M.’s brain based on histological sectioning and digital 3D reconstruction. Nat Commun 5, 3122 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4122

Corkin S. (2002). What’s new with the amnesic patient H.M.?. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 3(2), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn726

Corkin, S. (2013). Permanent Present Tense: The Unforgettable Life of the Amnesic Patient, H.M. New York: Basic Books.

Dittrich, L. (2016). Patient H.M: A story of memory, madness and family secrets. New York: Random House.

Eichenbaum, H., Morton, T., Potter, H., & Corkin, S. (1983). Selective olfactory deficits in case H. M. Brain, 106, 459–472.

Hilts, P. J. (1996). Memory’s Ghost: The Nature Of Memory And The Strange Tale Of Mr. M. United Kingdom: Simon & Schuster.

Scoville, W. B. (1954). The Limbic Lobe in Man, Journal of Neurosurgery, 11(1), 64-66. https://doi.org/10.3171/jns.1954.11.1.0064

Scoville, W. B., & Milner, B. (1957). Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry, 20(1), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.20.1.11

The first Director was

The first Director was  Take note of the remarkable trees and

Take note of the remarkable trees and

William Beecher Scoville

William Beecher Scoville Mr. Henry Molaison (known to the world as HM) was experiencing severe epileptic seizures. Mr. Molaison had his first appointment with Dr. Scoville around 1943. He was admitted several times to Hartford Hospital for pneumoencephalograms that were normal and EEG studies that only showed scattered activity not a single focus. Dr. Scoville suggested surgery. Dr. Scoville had performed similar surgeries for people with psychiatric disorders but not for people with seizure disorder, and the results of his surgeries were mixed. They were mostly performed on women who were confined to state hospitals in Connecticut and diagnosed with schizophrenia, although a few also had epilepsy. Unexpectedly, the surgery designed to treat the psychosis seemed to make the epilepsy better.

Mr. Henry Molaison (known to the world as HM) was experiencing severe epileptic seizures. Mr. Molaison had his first appointment with Dr. Scoville around 1943. He was admitted several times to Hartford Hospital for pneumoencephalograms that were normal and EEG studies that only showed scattered activity not a single focus. Dr. Scoville suggested surgery. Dr. Scoville had performed similar surgeries for people with psychiatric disorders but not for people with seizure disorder, and the results of his surgeries were mixed. They were mostly performed on women who were confined to state hospitals in Connecticut and diagnosed with schizophrenia, although a few also had epilepsy. Unexpectedly, the surgery designed to treat the psychosis seemed to make the epilepsy better.

.

.  2 Congress Street

2 Congress Street

Mr. Molaison was born on February 26, 1926 in Manchester, CT. As a child he began to have absence seizures. His mother attributed the onset of seizures to a bicycle accident he had when he was ten, but there was also a family history of epilepsy on his father’s side. On his fifteenth birthday he experienced his first tonic-clonic grand mal seizure. After that his seizures made it difficult for him to participate in social activities, to drive, or to finish school. He started at Willimantic High School but dropped out. He then enrolled at East Hartford High but did not partake in any extracurricular activities besides Science Club.

Mr. Molaison was born on February 26, 1926 in Manchester, CT. As a child he began to have absence seizures. His mother attributed the onset of seizures to a bicycle accident he had when he was ten, but there was also a family history of epilepsy on his father’s side. On his fifteenth birthday he experienced his first tonic-clonic grand mal seizure. After that his seizures made it difficult for him to participate in social activities, to drive, or to finish school. He started at Willimantic High School but dropped out. He then enrolled at East Hartford High but did not partake in any extracurricular activities besides Science Club.  After graduation he had various jobs, including at the Underwood Typewriter Company on Arbor Street in Hartford (where Real Art Ways currently is). He took large doses of anti-seizure medications.

After graduation he had various jobs, including at the Underwood Typewriter Company on Arbor Street in Hartford (where Real Art Ways currently is). He took large doses of anti-seizure medications. After the surgery he lived at 63 Crescent Drive in East Hartford and he could accurately draw the floor plan of that house. He had been very close to his parents and was upset each time he was reminded they had died, but then they would soon slowly come back to life in his mind. For a while, Henry made a habit of carrying around a little scrap of paper reminding him that his father was dead.

After the surgery he lived at 63 Crescent Drive in East Hartford and he could accurately draw the floor plan of that house. He had been very close to his parents and was upset each time he was reminded they had died, but then they would soon slowly come back to life in his mind. For a while, Henry made a habit of carrying around a little scrap of paper reminding him that his father was dead.

From Annese et al. (2014): The fixed specimen was photographed after removal of the leptomeninges. Evidence of the surgical lesions in the temporal lobes is highlighted by white geometric contours (a, b). A mark produced by the oxidation of one of the surgical clips inserted by Scoville is visible on the parahippocampal gyrus of the right hemisphere (black arrow). (c) encloses a lesion in the orbitofrontal gyrus that affects the cortex and WM. Marked cerebellar atrophy is consistent with H.M.’s long-term treatment with phenytoin.

From Annese et al. (2014): The fixed specimen was photographed after removal of the leptomeninges. Evidence of the surgical lesions in the temporal lobes is highlighted by white geometric contours (a, b). A mark produced by the oxidation of one of the surgical clips inserted by Scoville is visible on the parahippocampal gyrus of the right hemisphere (black arrow). (c) encloses a lesion in the orbitofrontal gyrus that affects the cortex and WM. Marked cerebellar atrophy is consistent with H.M.’s long-term treatment with phenytoin.