Surprises Between Pages

[Posted by Erika Jenns, Indiana University ’13]

A book’s history is comprised of more than an author’s thoughts put down on a page; it extends to and is largely dependent on the reader. The importance of the reader’s experience with the book lies in the finer details: the coffee stains, the hand-written notes, and the tiny remnants of life left between pages. A reader desires a relationship with the text, and as in any other relationship, he or she will inevitably leave pieces of himself or herself behind.

After brief encounters with 71 of Lydia Sigourney’s published works, it pains me to come across a book that appears never to have indulged in such a wonderful affair. Was there no reader to connect with the text? Did it sit idle on a bookstore shelf waiting to be purchased? How can it be that this text does not bear a single mark of understanding, confusion, enlightenment, or love? Luckily, I have stumbled across scribbled notes and children’s drawings more often than not, or at least often enough to feed my desire for proof of personal relationships with Sigourney’s texts.

Evidence of one such relationship can be seen in a copy of Zinzendorff, and Other Poems. A needlework cross, backed in satin ribbon is inserted between the pages of a poem titled “The Dead Horseman.” The initials “IHS” grace the top of the piece and represent the Christogram, an abbreviation for Jesus Christ. It is likely that it was used as a bookmark and was created by the young woman whose name can be found in an inscription on the first title page, “Miss Catherine Bueno [?] from H. P. J.”

Evidence of one such relationship can be seen in a copy of Zinzendorff, and Other Poems. A needlework cross, backed in satin ribbon is inserted between the pages of a poem titled “The Dead Horseman.” The initials “IHS” grace the top of the piece and represent the Christogram, an abbreviation for Jesus Christ. It is likely that it was used as a bookmark and was created by the young woman whose name can be found in an inscription on the first title page, “Miss Catherine Bueno [?] from H. P. J.”

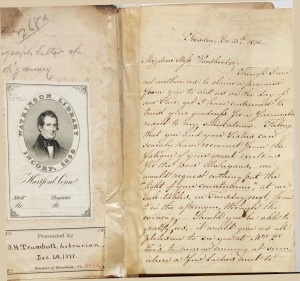

Several of Sigourney’s books have similarly personal pieces nestled between their pages. One example is a copy of Sketch of Connecticut, Forty Years Since. A letter has been taped into the gutter of the front endpapers, and despite its crumbling appearance, it illustrates the personal relationship that Sigourney had with the text and the woman to whom she addressed the letter.

My Dear Miss Woodbridge,

Though I am not authorized to claim a promise from you to aid us on the day of our Fair, yet I have continued to trust your goodness for a favorable result to my solicitations. Feeling that you and your Sisters can scarcely have recovered from the fatigue of your great exertions for the poor Mohegans [?], we would request nothing but the “light of your countenance,” at our sale-tables, on Tuesday next, from 2 in the afternoon, through the evening. Should you be able to gratify us, it would give us all pleasure to see you at Mrs. Dr. Lee’s tomorrow evening at seven, where a few ladies meet to consult about arrangements for the Fair, particularly respecting the decoration of the Hall where it will be held, with greens, in honour of the approaching Christmas.

with love to your sisters, -yours affectionately, L. H. Sigourney”

A copy of Sigourney’s Sketches, also contains some pasted in notes. Within the essay “The Family Portraits,” in the gutter of pages 128 and 129, there is a pasted in note. It elaborates on the relationships between the people described in the essay including, her husband, Charles Sigourney. Charles was involved in the founding of Trinity College. He was the first secretary of the Trinity Trustees.

A copy of Sigourney’s Sketches, also contains some pasted in notes. Within the essay “The Family Portraits,” in the gutter of pages 128 and 129, there is a pasted in note. It elaborates on the relationships between the people described in the essay including, her husband, Charles Sigourney. Charles was involved in the founding of Trinity College. He was the first secretary of the Trinity Trustees.

“Mary Ronchon, granddaughter of John Beauchamp, (pronounced in the French, not the English manner,) was the grandmother of Charles Sigourney, one of the original Trustees of the College and Mrs. Sigourney’s husband. John Beauchamp removed with his family from Boston to Hartford, where he died Nov. 14, 1740, in his 88th year. One of his daughters was mother of John Laurence, Treasurer of Connecticut 1769-1789, who was greatgrand-father of William Roderick Laurence, of 1856, who gave to the college the portrait of Bp. Berkley copied by him from the picture in Yale College, and also gave a collection of coins and one of autographs. Another daughter of John Beauchamp was wife of John Michael Chenevard, and ancestors of John Chenevard Comstock of the class of 1838. Charles S. Hoadly.”

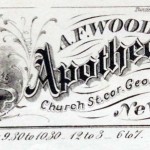

Relationships with Sigourney’s texts were not reserved for adults; in an 1844 copy of Sigourney’s Select Poems, a child’s drawing has been left behind. It resides within the pages of her poem “The Volunteer” and depicts a cracked tombstone. The inscription on the tombstone reads, “Elizabeth ghter [sic] of Joshua & Sar7 [sic] Chandie died March 11th 1758 in her 3rd year.” The drawing has been made on the verso of a small slip of paper that came from the A. F. Wood Apothecary in New Haven, Connecticut.

Relationships with Sigourney’s texts were not reserved for adults; in an 1844 copy of Sigourney’s Select Poems, a child’s drawing has been left behind. It resides within the pages of her poem “The Volunteer” and depicts a cracked tombstone. The inscription on the tombstone reads, “Elizabeth ghter [sic] of Joshua & Sar7 [sic] Chandie died March 11th 1758 in her 3rd year.” The drawing has been made on the verso of a small slip of paper that came from the A. F. Wood Apothecary in New Haven, Connecticut.

Evidence of a more sentimental bond can be found in a copy of Sigourney’s Evening Readings in History. This copy is dedicated to her son Andrew. The inscription reads, “Little Andrew from his Mama.” Andrew was Sigourney’s only son, and one of only two children that survived from infancy.

While there are many more books in the Watkinson’s collection of Sigourney’s works with inscriptions, annotations, and various tidbits of reader’s lives, the five instances described above provide a glance into the secret lives hidden behind gold stamped covers and between roughly cut pages. These descriptions are proof that there is more to a text than what the author puts on paper and sends to print; a reader’s relationship with a text is just as influential in the journey it takes.