Some Chinese Ghosts

[Posted by Mariah West for AMST 838: America Collects Itself, from Colony to Empire]

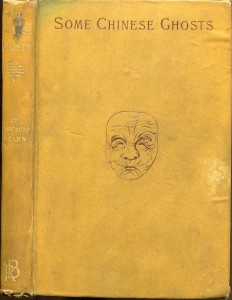

Originally, in delving into the depths of the Watkinson search engine, I found this book purely through my own personal whimsy. I was searching through the subject of mythology and this unassuming book appeared—but what a title! When I held this well-loved and well-worn book in my hands, I was charmed by its stained and dulled cover and its inscription from the original owner—Daisy Foster. Nothing about this book was personalized beyond that—no annotations, no folded pages. Nothing but an index card, apparently from a book dealer from whom it was purchased guaranteeing a good price based on recent auctions. For approximately $35 this book was purchased by Dr. Jerome P. Webster, who donated his collection of Far Eastern and Maritime books to the Watkinson in 1910. Why this was such a good deal became apparent when searching for the origins of this edition—in some sort of disorganized confusion, the publishers believed that Lafcadio Hearn disliked the mustard yellow cover and wanted it reprinted. They chose to burn the majority of this printing, but several copies escaped, including this copy filed away in the belly of the Watkinson!

Originally, in delving into the depths of the Watkinson search engine, I found this book purely through my own personal whimsy. I was searching through the subject of mythology and this unassuming book appeared—but what a title! When I held this well-loved and well-worn book in my hands, I was charmed by its stained and dulled cover and its inscription from the original owner—Daisy Foster. Nothing about this book was personalized beyond that—no annotations, no folded pages. Nothing but an index card, apparently from a book dealer from whom it was purchased guaranteeing a good price based on recent auctions. For approximately $35 this book was purchased by Dr. Jerome P. Webster, who donated his collection of Far Eastern and Maritime books to the Watkinson in 1910. Why this was such a good deal became apparent when searching for the origins of this edition—in some sort of disorganized confusion, the publishers believed that Lafcadio Hearn disliked the mustard yellow cover and wanted it reprinted. They chose to burn the majority of this printing, but several copies escaped, including this copy filed away in the belly of the Watkinson!

At first I was hesitant in reading this book. I thought that I would be disappointed in the treatment of the legends and the myths of China—especially ones that were translated at the height of exoticism and anti-Chinese sentiments in the United States. I was pleasantly surprised to find the contents to be lovingly and respectfully presented with great care to maintain their origins. I suspect that a great deal of this care comes from Lafcadio Hearn’s own background of isolation, abandonment, and disrespect as well as his great enjoyment of the different and unknown.

At first I was hesitant in reading this book. I thought that I would be disappointed in the treatment of the legends and the myths of China—especially ones that were translated at the height of exoticism and anti-Chinese sentiments in the United States. I was pleasantly surprised to find the contents to be lovingly and respectfully presented with great care to maintain their origins. I suspect that a great deal of this care comes from Lafcadio Hearn’s own background of isolation, abandonment, and disrespect as well as his great enjoyment of the different and unknown.

This book contains six legends formatted into a short story. There is “The Soul of the Great Bell,” “The Story of Ming-Y,” “The Legend of Tchi-Niu,” “The Return of Yen-Tchin-King,” “The Tradition of the Tea-Plant,” and “The Tale of the Porcelain-God.” Each story features important explanations of traditional Chinese morality and duties portrayed with florid and picturesque language. While the majority of the stories do have a horrific and violent end, much like the tradition of the Grimm Brother’s European fairy tales, the reader cannot help but become swept up in the fantastical descriptions that Hearn paints for her. Each story conveys the importance and the interest in material goods that was a part of dynastic China—nothing is regarded higher than artistry and the self-sacrifice that is pursued within these stories.

With “The Soul of the Great Bell,” we follow the journey of an artist and his daughter who have been ordered by the Emperor, a demi-god, to make the grandest bell in the history of China. The artist will always fail at his goal, the daughter soon learns, until his bell is forged with the sacrificial blood of a virgin. Upon the threat of her father’s death, the daughter throws herself into his forge and becomes immortalized through the bell due to her filial piety.

In “The Story of Ming-Y,” we follow the trials and tribulations of the young and brilliant Ming-Y as he finds a job as a tutor with a wealthy family and meets a beautiful woman. Ming-Y and the woman, Sië, fall madly in love and pursue a secret affair. Shortly Ming-Y is discovered through his exhaustion that he has been spending nights away from where he is supposed to be. Both his father and his employer are incredibly concerned and confront him, and force Ming-Y to introduce them to Sië. When Ming-Y attempts to bring them to her home where they had been meeting, they find nothing but a tomb.

“The Legend of Tchi-Niu” follows a poor but pious man named Tong-yong who was orphaned at an early age. In order to have his father buried properly he sold himself into slavery. While his life as a slave was miserable, Tong-yong maintained his ancestors’ graves as was required and spent much time practicing his family worship. Eventually, Tong-yong met an incredible woman who promised to provide. As time went on, she was able to buy Tong-yong’s freedom and secure a house and land for him to farm through her amazing skills with silk weaving. Once his freedom was secured, they had a child who was the most gifted and brilliant child ever seen. One night, his wife came to Tong-yong and told him she must leave them. She was a goddess sent by the Master of Heaven to reward him for his dedication to filial piety.

“The Return of Yen-Tchin-King” follows the illustrious heroics of the Supreme Judge from one of the Six August Tribunals who was commanded by the Emperor, the Son of Heaven, to control a revolt. Yen-Tchin-King was so loyal to the Emperor and the Master of Heaven that he could not be swayed into betraying his master’s even at the threat of his own life. When the rebels executed him, he passed on to serve the Master of Heaven who rewarded his greatness, wisdom, and virtue with a corpse that would never corrupt of decay and would become an emblem of justice for the future generations.

“The Tradition of the Tea-Plant” follows the painful but moral story of the origin of the tea plant—something obviously important to the social and traditional customs of China. A young ascetic monk finds distraction and temptation within a beautiful young woman. Beauty this corporal world is so fleeting and illusionistic that is should not draw the monk away from his spiritual journey. But alas—he cannot return to his meditation. In a final attempt to seek enlightenment while ignoring his desires he slices off his eyelids and throws them to the ground. From his sacrifice grows the sacred tea-leaf, forever mimicking their original form.

Finally, “The Tale of the Porcelain-God,” which is by far my most favored of these legends. While very similar to “The Soul of the Great Bell,” this story follows the grand tradition of porcelain and vase-making within the dynastic periods of China’s history. Once a great potter was so revered and respected for his talent that the Emperor of China called upon him to produce a vase that resembled human flesh. Try as he could, the potter created the most beautiful vases, but not one could compare to human flesh. In his despair over the Emperor’s disappointment and threatening advances against the artist’s life, he contacted and begged the Porcelain-God who resided within his kiln. A deal was made to produce a vase that resembled human flesh, something that could only be achieved when the vase itself contained the spirit of a human. In his final attempt, the potter made the most wondrous vase, painted it with care, and threw himself into the fire with his last piece. When the fires died down and the vase was removed from the kiln, it was like no other—appearing to breath and with the sumptuous undertones of flowing blood. The artist would live forever contained within his most prized work.

This book also contains a glossary of Chinese words which have not been translated into English for the fear of mistranslation and the desire to maintain authenticity within the stories. This glossary is, at least to me, a very impressive inclusion to a book from the 1880s, although it probably had much to do with the popular exoticism and orientalism of aesthetic practices during the 18th and 19th centuries.