[Posted by Margaret Pallis for AMST 851: The World of Rare Books (Instructor: Richard Ring)]

The item in the Watkinson that caught my attention was a primer from circa 1880. The text, Little Birdie’s Picture Primer, was published by George Routledge and Sons. The book appealed to me because I’ve been interested in literature written for children for quite a while now. The book also relates, tangentially, to my thesis (which I am in the process of writing) on children’s fiction of this era. In my thesis, I am examining the didacticism inherent in literature written for children and, more specifically, how some particular texts written in the mid-19th to mid-20th century can impact children’s lives. It is possible to suggest that a text like Little Birdie’s Picture Primer was designed specifically to mold children in very specific ways. Consequently, when I was looking through the extensive collection that the Watkinson contains, I became interested in the primers. I wanted to see if these books, which are highly didactic in nature, as they were used to teach children to read and write also had a more social or political stance as well.

The item in the Watkinson that caught my attention was a primer from circa 1880. The text, Little Birdie’s Picture Primer, was published by George Routledge and Sons. The book appealed to me because I’ve been interested in literature written for children for quite a while now. The book also relates, tangentially, to my thesis (which I am in the process of writing) on children’s fiction of this era. In my thesis, I am examining the didacticism inherent in literature written for children and, more specifically, how some particular texts written in the mid-19th to mid-20th century can impact children’s lives. It is possible to suggest that a text like Little Birdie’s Picture Primer was designed specifically to mold children in very specific ways. Consequently, when I was looking through the extensive collection that the Watkinson contains, I became interested in the primers. I wanted to see if these books, which are highly didactic in nature, as they were used to teach children to read and write also had a more social or political stance as well.

Before I discuss the particular primer that I selected for this discussion, a bit of history about primers seems appropriate. Primers were intended as instructional texts for children, principally in terms of religious or spiritual development. Primer was the original name for a prayer-book, and these were “simple books for teaching children their letters, prayers, and later, other simple subjects” (“Primers”). Primers have a long history, and early versions were found in the middle ages. When doing a bit of research on primers, I was reminded of the fact that in Chaucer’s “The Prioress’s Tale” there is a reference to a child who “sat in the scole at his prymer” (“Primers”). While this was an interesting tidbit, the information was also useful in reminding me that the primer was a significant text for children. By the end of the 18th century, primers moved from being religious texts for children and moved to more secular learning tools (“Primers”). The primer I selected from the Watkinson is of the latter type as it is not about religious instruction.

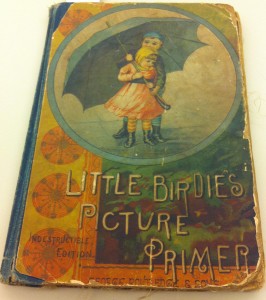

Upon first examining the book from the Watkinson collection, I amazed by the appearance of the book. For a children’s book that was published in the 1880’s, it appears to be in good condition, though it certainly shows evidence of being used in the past and likely by children. This primer is apparently an 1800 version of the cloth or plastic or hard cardboard books we now produce for young children as the publisher claims, on the cover, that this particular book is the “indestructible edition.” The book itself appears to be made of a hard cardboard, and the spine is cloth-covered. The pages of the book are made of linen, and it appears to have been well-read as there is light staining along the outer edges of all of the pages, indicating use. The front cover is brightly colored, with an illustration of a young boy and girl under an umbrella. The title of the book is in an engaging font (one that would appeal to children) which is staggered a bit across the front. The back cover is a repeating picture of frolicking children. There is a good deal of wear on the corners of the book, front and back. The last page of the book shows a good deal of wear and, like the first page, is affixed to the inside cover.

Upon first examining the book from the Watkinson collection, I amazed by the appearance of the book. For a children’s book that was published in the 1880’s, it appears to be in good condition, though it certainly shows evidence of being used in the past and likely by children. This primer is apparently an 1800 version of the cloth or plastic or hard cardboard books we now produce for young children as the publisher claims, on the cover, that this particular book is the “indestructible edition.” The book itself appears to be made of a hard cardboard, and the spine is cloth-covered. The pages of the book are made of linen, and it appears to have been well-read as there is light staining along the outer edges of all of the pages, indicating use. The front cover is brightly colored, with an illustration of a young boy and girl under an umbrella. The title of the book is in an engaging font (one that would appeal to children) which is staggered a bit across the front. The back cover is a repeating picture of frolicking children. There is a good deal of wear on the corners of the book, front and back. The last page of the book shows a good deal of wear and, like the first page, is affixed to the inside cover.

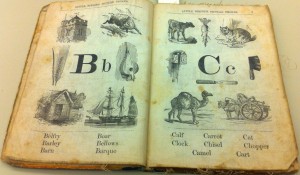

The text itself boasts that it includes over 200 illustrations. The book is clearly intended to teach the alphabet (both the Roman letters and script) and the numbers one through twelve. As the text introduces each letter, there are a series of pictures of items or animals that begin with that letter. For each letter, there are six or seven words with corresponding pictures. Where I became particularly interested was with the inclusion of some words that seemed strongly based in political or social hierarchy. For example, this book teaches children about words like “earl,” “gun,” “globe,” “herald,” “king,” and “queen.” These words clearly denote a particular mindset. While king and queen are probably still in children’s books, the inclusion of a word like “earl” suggests that the word selection was intentionally designed to support the political system of the time.

The political system (along with the lesson that this text is attempting to inculcate) becomes even more apparent in the section of the text that uses the words in sentences. It becomes clear that the goal of this book is not just to teach the letters and words, but also to help children to understand what is appropriate in society and who has authority. The following sentences, form “G” to “L” indicate the nature of the text: “G was a gypsy who lives in a tent,” “I was an idler and wasted his time,” “J was a justice who punished all crime,” “K was a knight fully armed cap-a-pie,” and “L was a lawyer and fond of his fee.” What becomes apparent, from these selections and further perusal of the book, is that the children are given a sense of words that begin with those letters (further cementing the lesson of the earlier part of the text), but there is also more direct instruction for the children about appropriate and inappropriate behaviors (i.e,. the idler and gypsy are clearly not favored by society). The illustration of the gypsy shows a woman with a small baby strapped to her back, standing in front of a dilapidated tent. But the book also casts dispersion on the lawyer, who seems only interested in money, unlike the justice that is referred to earlier.

The numbers, in contrast to the letters, do not appear to present the same sort of lesson. Instead, the numbers simply reference elements one might find in the natural world, such as “One Hare,” “Five Fowls,” and “Ten Sheep.” The book also contains a seek and find picture, in which the child is supposed to find a horse, boy, girl, and tree. However, the images are quite easy to find, likely because this book was intended for a young child (a pre-reader).

I found this text particularly interesting to examine, as I felt like I was taking a step back into history and was able to get a sense of the kinds of instructional materials available for young children. Certainly, the text gave me a sense of what adults found was important for children to know. I also think the publisher might be right; this apparently was an “indestructible edition.” As a book for children, it appears to have withstood a good deal of use.