Anne Bradstreet

[Posted by Sara Mowery for AMST 838: America Collects Itself, from Colony to Empire]

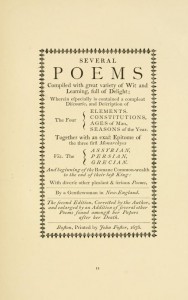

Anne Bradstreet’s collected poems, edited by John Harvard Ellis, was published in 1867 by A. E. Cutter in Charlestown, and bears the mark “No. 157 of 250 copies printed.” Ellis’s Preface provided me with reassurance that this edition would indeed hold true, if not exact, to the first edition of Bradstreet’s works which was published during her lifetime in London in 1650. Specifically, Ellis explains that at the time of his edition there had been three published editions of Bradstreet’s collected works. The first (1650), a second published in Boston in 1678 six years after Bradstreet’s death, and a third published from the second edition in 1758, also in Boston. Ellis notes that the third edition contains “numerous omissions of words, changes in spelling, and other alternations of little importance.” In his edition, Ellis paid careful attention to maintaining the integrity of the second edition of Bradstreet’s collection thereby, it would appear, dismissing any value in the third edition. The second edition, Ellis notes, “contained the additions and corrects of the author, and several poems found amongst her papers after her death.” In other words, the second edition is a more exhaustive collection of Bradstreet’s work. It also provides “extensive” corrections to both spelling and grammar.

Anne Bradstreet’s collected poems, edited by John Harvard Ellis, was published in 1867 by A. E. Cutter in Charlestown, and bears the mark “No. 157 of 250 copies printed.” Ellis’s Preface provided me with reassurance that this edition would indeed hold true, if not exact, to the first edition of Bradstreet’s works which was published during her lifetime in London in 1650. Specifically, Ellis explains that at the time of his edition there had been three published editions of Bradstreet’s collected works. The first (1650), a second published in Boston in 1678 six years after Bradstreet’s death, and a third published from the second edition in 1758, also in Boston. Ellis notes that the third edition contains “numerous omissions of words, changes in spelling, and other alternations of little importance.” In his edition, Ellis paid careful attention to maintaining the integrity of the second edition of Bradstreet’s collection thereby, it would appear, dismissing any value in the third edition. The second edition, Ellis notes, “contained the additions and corrects of the author, and several poems found amongst her papers after her death.” In other words, the second edition is a more exhaustive collection of Bradstreet’s work. It also provides “extensive” corrections to both spelling and grammar.

“I changed my condition and was married, and came into this country, where I found a new world and new manners, at which my heart rose. But after I was convinced it was the way of God, I submitted to it and joined the church at Boston.” [i] This recollection, shared by Anne Bradstreet with her children once many years settled, speaks volumes to a woman’s position and identity in Puritan colonial society. Specifically, a woman’s duty was to submit, be it to God or to husband, and most preferably to both. Yet Anne Bradstreet would do something remarkable for her times. She would become the first published female poet in colonial America. A female voice, un-muted. Bradstreet first came to my attention in a survey undergrad American Literature course. We read a handful of her poems and spent all of five minutes discussing her work and life in class. Remarkable, in my opinion, given Bradstreet’s significant accomplishment. And so I chose for this post to delve deeper into why Bradstreet’s voice carried while so many female voices were muted in colonial America.

I have briefly encountered another colonial America Anne during my studies – Anne Hutchinson. While this post is not about Hutchinson, and I will not devote any great length to a discussion on Hutchinson, it is important to make note of Hutchinson because her banishment from society stands in stark contrast from the acceptance that Anne Bradstreet received. Bradstreet’s female voice won over her contemporaries, rather than inciting their wrath as Hutchinson’s had. Hutchinson and Bradstreet were contemporaries, somewhat. Anne Hutchinson settled in America from 1634 to 1643 and Anne Bradstreet from 1630 to 1672. They lived among the same Puritan settlers under similar male confines. So why did Hutchinson’s voice get her banished while Bradstreet’s voice was rewarded with the ultimate prize for a writer; being published? For an answer I look to how the two women chose to express themselves. Anne Hutchinson’s voice was fervent and oppositional; she directly challenged the ministry. Anne Bradstreet on the other hand sneaked in through the back door; her writings left much room for interpretation. Her voice was equally challenging; not in its demanding strength but in its crafty manipulation.

By way of example, I look to To my Dear and Loving Husband.

If ever two were one, then surely we.

If ever man were lov’d by wife, then thee;

If ever wife was happy in a man,

Compare with me ye women if you can.

At first reading, this is a love poem written by a devoted wife. She expresses not only her love but also urges others to look to this couple as an example of married bliss. However, Bradstreet’s words quickly force us to question if there is perhaps more she is trying to tell us when she continues:

I prize thy love more than whole Mines of gold,

Or all the riches that the East doth hold.

My love is such that Rivers cannot quench,

Nor ought but love from thee, give recompence.

These lines speak of such trivial matters of earthly possessions and payment. She attempts to place a size and value on love. In this, Bradstreet has strayed from the ethereal to the earthly; and in doing so, she diminishes the value of love. If her love can be compared to such an earthly thing as a mineral, if a value can be placed upon it, if it can be measured, surely its magnificence is overrated.

Thy love is such I can no way repay,

The heavens reward thee manifold I pray.

Then while we live, in love lets so persever,

That when we live no more, we may live ever.

Anne Hutchinson’s story reveals a rift in Puritan society between those who preached the covenant of grace and those who preached the covenant of works. In the above lines I hear Bradstreet’s musings on this debate. She speaks of salvation; “heavens reward,” and tells her husband that “while [they] live, in love let’s so persever.” Her practical approach is to deal with the here and now, loving her husband while they live, so that they may enjoy eternity together. It is in these final lines of the poem that I believe Bradstreet’s female voice speaks out against the contentious debate that plagued Puritan society. Softly and cleverly hidden in endearing terms of affection towards her husband, Anne Bradstreet gives her own interpretation of salvation and how one can attain it.

Another example of Bradstreet’s ability to express herself in an unforgiving puritan society is in The Prologue. Here, Bradstreet’s use of epic genre invokes classical style:

To sing of Wars, of Captains, and of Kings,

Of Cities founded, Common-wealths begun,

For my mean pen are too superior things:

Or how they all, or each their dates have run,

Let Poets and Historians set these forth,

My obscure Lines shall not so dim their worth.

In using this genre and style, Bradstreet mimics the writing style of the Great Men; a style well accepted throughout history. In doing so, Bradstreet sneaks onto the scene. Yes she is a woman. But her style is familiar, and therefore, she is allowed to continue. She cleverly carries this deceit forward in the next stanza where she hides within her theme, simply mimicking her muse, Bartas:

A Bartas can, do what a Bartas will

But simple I according to my skill.

Bradstreet has set the scene for us. We are safe to read on, un-threatened by the humble female voice. Yet in the blink of an eye she springs on us, as if glaring at the reader, knitting needles angrily click-clacking, body tense:

I am obnoxious to each carping tongue

Who fays my hand a needle better fits,

A Poets pen all scorn I should thus wrong,

For such despite they cast on Female wits:

If what I do prove well, it won’t advance,

They’l say it’s stoln, or else it was by chance.

The once self-diminishing and humble Puritan wife is now the combative and angry Poet. She angrily calls out society and its “carping tongue” that insist a woman’s voice is better silenced; a woman’s place is in the home. She is no feeble-minded female. Her “Poets pen” is guided not by accident or chance but rather by an intelligent “female wit.” The next stanza shows us just how clever Bradstreet’s Poetic pen could be:

Let Greeks be Greeks, and women what they are

Men have precedency and still excel,

It is but vain unjustly to wage warre;

Men can do best, and women know it well

Preheminence in all and each is yours;

Yet grant some small acknowledgement of ours.

With this stanza Bradstreet speaks in more conciliatory tones, gradually calming the reader down. In a single breath she acknowledges a man’s “precedency” and “preheminence” while also asking that her female voice be judged not by its femininity but by the intelligence that guides it. The entire poem is a whirlwind of emotion and manipulation.

From the role of diminutive sex to angry feminist to well-reasoned litigator, The Prologue and To My Dear and Loving Husband are prime examples of Anne Bradstreet’s clever use of manipulative language and style that would save her from a fate similar to Anne Hutchinson. Anne Bradstreet’s works survive today, neatly bound and displayed in library stacks worldwide. Ironically, Cotton Mather, the grandson of John Cotton and turncoat of Anne Hutchinson, would sing Anne Bradstreet’s praise, writing that her poems “have afforded a grateful entertainment unto the ingenious, and a monument for her memory beyond the stateliest marbles.” [ii] Thankfully, time alters perspective; the female voice of each Anne has survived history in spite of those who believed such a voice should not.