[Posted by Julia Falkowski (’13), for Jonathan Elukin’s History of the Book course]

While exploring the Watkinson for a book to examine for the course, a small, elaborately decorated leather spine caught my eye. The pattern on the spine consisted of alternating suns and moons, giving the book a gypsy-like feel. In size, the book was 5”x2 ¾”or about the size of a deck of cards. Something about the romantic decorations combined with the petit size gave the book an air of mystery and magic.

While exploring the Watkinson for a book to examine for the course, a small, elaborately decorated leather spine caught my eye. The pattern on the spine consisted of alternating suns and moons, giving the book a gypsy-like feel. In size, the book was 5”x2 ¾”or about the size of a deck of cards. Something about the romantic decorations combined with the petit size gave the book an air of mystery and magic.

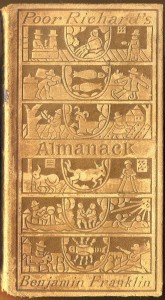

I picked it up not knowing what to expect. Examining the cover, I was somewhat shocked to learn that this mystical looking book was actually an 1898 edition of Benjamin Franklin’s Poor Richard’s Almanack. The leather cover was decorated with a mix of horoscope signs and pastoral American scenes. Upon inspecting the inside, I found that it was a sort of “Best of” Poor Richard’s, with selections from editions of the Almanack ranging in year from 1733 to 1758. In the back was a facsimile re-print of Franklin’s very first 1733 Almanack.

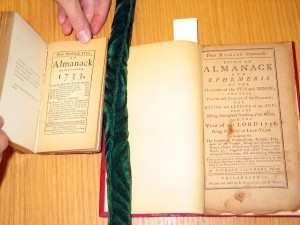

I discussed my find with Watkinson curator Rick Ring. He mentioned that the Watkinson possesses an original copy of Franklin’s 1756 almanac, and suggested I take a look at that as well. Rick brought the original almanac out and I realized that, despite the fine quality of the 1898 edition, the 1756 edition was the more exciting find. The 1756 edition has an actual connection to a living Franklin. One can imagine the industrious Franklin working diligently at his press into the late hours of the night to produce the pages I held in my hand. Of course, this fantasy neglects the likelihood that Franklin had hired drones to do the bulk of the printing work by that time of his life. Regardless, the fact remains that Franklin lived at the time this almanac was produced, and was intimately involved in overseeing its production.

Comparing the two almanacs proved an interesting exercise. The original looked older (of course) but it also looked much more used. The 1898 version, though over a hundred years old, looked almost as if it came straight from the bookstore. The more recent version also appears nicer; the pages are gilded and cut exactly to be exactly the same size, the paper is thick and sturdy. Comparatively, the pages in the original are thin and not all cut to the same size. No effort to achieve luxury seems to have been made with the original edition; it is quite utilitarian. Interestingly enough, though the original seems more suited to everyday use, it is substantially larger than the reprint, with dimensions of 7”x4”. The reprint seems more pocket-sized, and therefore, more convenient for everyday use. But then again, the work that has to go into making something small often indicates luxury. Take for example the ever-smaller cell phones and ipods of today.

One question that came to mind about the re-print was a simple: Why? What about the culture of 1898 America created a market for this product? Unlike many modern reprints of books, there is no long-winded introduction explaining the cultural situation that accommodates publishing. One hint at why the almanac was put out can be found in the publisher. This re-printed almanac was produced by the Century Company, a New York publishing enterprise that began in 1881 and was particularly successful around the turn of the century. In 1930, the company was absorbed by another, and disappeared for a while. The company was revived in 2007 as a branch of Grand National Media. All the information I learned about the Century Company, I found on the modern Century Company’s website.

In its heyday, Century Publishing was famous for its periodical, The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine. The company showed a particular interest in producing historical works. Their most successful endeavor was an 1880s series of articles on the history of the Civil War. In 1898, the company was at the pinnacle of its success. They had the resources to put out luxury facsimiles of any books they wanted to. And what better for a company concerned with the preservation of American history than a re-print of one of the most famous publications by one of the most prominent men of early America?

In its heyday, Century Publishing was famous for its periodical, The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine. The company showed a particular interest in producing historical works. Their most successful endeavor was an 1880s series of articles on the history of the Civil War. In 1898, the company was at the pinnacle of its success. They had the resources to put out luxury facsimiles of any books they wanted to. And what better for a company concerned with the preservation of American history than a re-print of one of the most famous publications by one of the most prominent men of early America?

As I looked at the two almanacs side-by-side, I was reminded of Franklin’s efforts to create a cohesive American nation. I felt like the success of his endeavour could be seen in the two books in front of me. The luxury Century edition, printed over one hundred years after Franklin’s death in 1790 combined my reverential interest in both of the almanacs seemed a testament to the continued existence of the patriotism that Franklin worked to foster.