[Posted by Dr. Scott Gwara, professor of English at the University of South Carolina]

Datable to about 1470, manuscript 7 in the Watkinson Library is a “Book of Hours,” a prayer-book widely used by the laity in Europe from about 1300 to 1550. These manuscripts were often illustrated with lavish paintings called “miniatures” or “illuminations.” Nearly all Books of Hours include an “Office of the Dead,” which is recited for deceased loved ones. Because the Office of the Dead has readings from the Book of Job, it also served as a personal reflection on mortality. A miniature in MS 7 reveals this emphasis in the extravagant depiction of a lady speared by Death in the presence of her knight [fig. 1]. Featured in some of the manuscript’s other miniatures, the lady doubtless depicts the book’s original owner. A zombie-like Death aims his dart at her abdomen. Will her demise result from appendicitis? Food poisoning? Or, since she walks in a private garden with her lover, perhaps childbirth?

Datable to about 1470, manuscript 7 in the Watkinson Library is a “Book of Hours,” a prayer-book widely used by the laity in Europe from about 1300 to 1550. These manuscripts were often illustrated with lavish paintings called “miniatures” or “illuminations.” Nearly all Books of Hours include an “Office of the Dead,” which is recited for deceased loved ones. Because the Office of the Dead has readings from the Book of Job, it also served as a personal reflection on mortality. A miniature in MS 7 reveals this emphasis in the extravagant depiction of a lady speared by Death in the presence of her knight [fig. 1]. Featured in some of the manuscript’s other miniatures, the lady doubtless depicts the book’s original owner. A zombie-like Death aims his dart at her abdomen. Will her demise result from appendicitis? Food poisoning? Or, since she walks in a private garden with her lover, perhaps childbirth?

While popular in the Renaissance, scenes of “Death and the Maiden” are exceptionally rare in Books of Hours. This distinctiveness enabled me to identify the manuscript as one of very few medieval books in antebellum America.

The Watkinson manuscript came from the collection of Joseph J. Cooke, a mercantile and real estate tycoon. When Cooke died in 1883, he left $5,000 to each of ten libraries in New England to buy his books at auction. Trinity College bought six manuscripts, including this lovely Book of Hours [Other Cooke manuscripts can be found at Yale, Brown, and the Providence Athenaeum].

The Watkinson manuscript came from the collection of Joseph J. Cooke, a mercantile and real estate tycoon. When Cooke died in 1883, he left $5,000 to each of ten libraries in New England to buy his books at auction. Trinity College bought six manuscripts, including this lovely Book of Hours [Other Cooke manuscripts can be found at Yale, Brown, and the Providence Athenaeum].

Cooke’s manuscript came from the collection of William Menzies, whose library was auctioned in in New York in 1876. A copy of the auction catalogue at Harvard records Cooke’s name as the buyer and the price he paid: $80. The catalogue quotes a certain “Rev. W. Bacon Stevens”: “it contains thirteen miniatures of grouped figures, one of which represents a lady, with a gaily attired knight, while Death in the form of a skeleton steals up from behind, and transfixes her with his dart.” This statement yields a clue to an even earlier owner.

Originally from Maine, William Bacon Stevens practiced medicine in Savannah from about 1838. There he met Alexander Augustus Smets (1769-1862), one of the wealthiest men in Georgia … and a voracious bibliophile. [Alexander Augustus Smets, from an engraving published in De Bow’s Review (1852): “[His library] has a reputation wide as the country, and scarcely a scholar or distinguished personage visits Savannah without seeking it out and feasting upon its contents.”]  Smets’ library of 5,000 books included twelve “ancient manuscripts,” one of them “Death and the Maiden.” In 1841 Stevens contributed an essay called, “The Library of Alexander A. Smets, Esq., Savannah” to the Magnolia, a Savannah monthly. He praised Smets’ library as “rich in ancient manuscripts,” writing the text cited above in the Menzies catalogue (“it contains thirteen miniatures of grouped figures,” etc.).

Smets’ library of 5,000 books included twelve “ancient manuscripts,” one of them “Death and the Maiden.” In 1841 Stevens contributed an essay called, “The Library of Alexander A. Smets, Esq., Savannah” to the Magnolia, a Savannah monthly. He praised Smets’ library as “rich in ancient manuscripts,” writing the text cited above in the Menzies catalogue (“it contains thirteen miniatures of grouped figures,” etc.).

As far as I can determine, Smets was only the third person in America to collect medieval and Renaissance manuscripts. Some of his medieval books survive at the New York Public Library, Indiana University, and Yale. One belongs to the Earl of Crawford in Scotland. Even more significantly, as Stevens’ article got re-published in newspapers, journals, and magazines, Smets’ manuscripts became the best known antebellum collection in North America, praised in Leipzig, Boston, New York, New Orleans, and London. Some of these reports express surprise that European patrimony had fallen into the hands of an American.

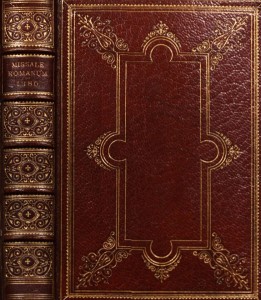

Smets’ manuscripts were auctioned in New York in 1868. Menzies probably bought “Death and the Maiden” at the sale. At that time the manuscript would have had Smets’ teensy autograph, “A. A. Smets Savannah” plus a date of acquisition. But the manuscript was re-bound, and the new binding explains why this Book of Hours has never before been associated with Smets. At the time, it was common even for the original bindings of medieval manuscripts to be replaced. Luckily, this manuscript did not have an original binding, and the new one by William Matthews is a bona fide treasure. Matthews was the leading binder in New York, and the first American genius of “bibliopegy”—the art of bookbinding.

Smets’ manuscripts were auctioned in New York in 1868. Menzies probably bought “Death and the Maiden” at the sale. At that time the manuscript would have had Smets’ teensy autograph, “A. A. Smets Savannah” plus a date of acquisition. But the manuscript was re-bound, and the new binding explains why this Book of Hours has never before been associated with Smets. At the time, it was common even for the original bindings of medieval manuscripts to be replaced. Luckily, this manuscript did not have an original binding, and the new one by William Matthews is a bona fide treasure. Matthews was the leading binder in New York, and the first American genius of “bibliopegy”—the art of bookbinding.

It’s always satisfying to uncover the provenance of medieval manuscripts, and it doesn’t get any better than this. Watkinson MS 7 not only represents the best of antebellum collecting in America but also conveys the afterlife of medieval books in second-, third-, and fourth-generation ownership.