The Fairy Family

[Post be Georgia Summers, ’15, for Jonathan Elukin’s History of the Book Course]

The Fairy Family: a series of ballads and metrical tales illustrating the fairy mythology of Europe was written by Archibald Maclaren and published by Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts in 1857. It is a collection of poetry based on the fairy folk, some of which are familiar and some of which are entirely new. It was illustrated by Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, who was known for being part of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. This was his first commission received and later on, he would deny any involvement, due to the amateur nature he perceived within his drawings. The illustrations for the book were recently displayed in the Pierpoint Morgan Library as the earliest examples of Burn-Jones’ work.

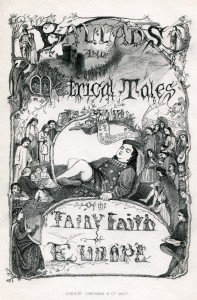

The binding itself is green, with gold colored decorations, most of which are nature-themed. On the spine, there is a picture of a fairy, as well as various creatures, including a snail and bird. On the inside, the title page is a wonderfully complex illustration, with fairies representing the letters. Unusually for a book of its time, the introduction retains the usage of the “long s” which looks like an unfinished ‘f’ instead of an ‘s’ at times.

Some of the creatures mentioned inside are common characters in children’s stories. The brownie, for example, is described as a “houfehold Spirit of the Scottifh low-lands and Borders.” Indeed, most of the creatures described here are specific to certain regions of the country. There are also plenty of others that are less commonly known, such as the Rafalki, or river nymph. Attempting to find out more proved difficult; the name does not turn up on any search engine, suggesting that this is a creature either entirely forgotten, or perhaps even made up by one of the poets in the collection.

This book is particularly unusual when placed in context with other books that Maclaren wrote throughout his lifetime. Maclaren is best know as the founder of the Oxford Gymnasium and his emphasis on exercise routines in the mid-19th Century. While the Oxford Gymnasium was originally used by the British Army for their training exercises, Maclaren spread his knowledge of the benefits of physical education, going so far as to write Military System of Gymnastic Exercises (1862) and Physical Education (1895), among other similar works.

So how is it that a medical man fixated on physical education came to write a book about fairies? There is little known about him that isn’t attached to his work on physical education. He was a scholarly character, not an artist. Perhaps, as his earliest work, it could be an attempt at a different career, or maybe a frivolous activity that occupied otherwise free time.

Maybe we’ll never know. We can only speculate.