Introduction

Magnet schools in Connecticut are part of a movement to allow parents and students to choose their school. The school choice system is an alternative to the traditional neighborhood public school system, which divides students into schools based on their neighborhood of residence and has often led to racial and socioeconomic segregation of public schools. “Choice” alternatives in the Hartford, CT area include district-wide open choice programs, interdistrict city-suburban transfer, charter schools, and interdistrict magnet schools. This essay will focus on racial diversity in interdistrict magnets, which have appealing alternatives themes and are open to all Connecticut children, regardless of their residence.

In Connecticut, the choice movement exploded after the landmark Sheff v. O’Neill ruling in 1996, in which the State Supreme Court ruled that the racial and socioeconomic segregation of Hartford’s school children violated the Connecticut Constitution. Though the goal of the Sheff movement is to integrate schools to have diverse student populations, the Hartford area magnet schools have remarkably different levels of minority populations. I am focusing on magnet schools in this essay because these schools are designed to have a specific racial balance in order to achieve the goal of desegregating Connecticut’s public schools, yet demographics play out differently depending on the school, and some schools are struggling to maintain their required desegregation standards. Interdistrict magnet schools are designed to attract students from all around the area and from all walks of life, but there are many factors that could affect which students end up applying to and attending the school, including both the school’s marketing strategies as well as qualities of the school. I hypothesize that two qualities that could have a major effect on student demographics are school location and school theme. In my analysis, I find that school theme has a bigger effect on demographics, with more minority students enrolling in schools focusing on college or career preparation while more white students enroll in niche-themed schools, with focuses such as STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) or the arts.

Desegregating Hartford’s schools: The controversy and the lack of transparency

Why does integration matter? In Connecticut today, there are 40,000 children attending chronically failing schools where most students are far below grade level. At these schools, nearly 90% of students are African American/black or Hispanic/Latino and come from low-income households, on average. Students of color bear the burden of Connecticut’s failing schools, in spite of the American ideal in which all children should have equal opportunity to learn and grow together.

However, in education reform, integration is a debated concept. According to the Sheff Movement, attending racially, economically, and culturally diverse schools leads to a “range of short and long term benefits for all racial groups. This includes gains in math, science, reading, and critical thinking skills and improvements in graduation rates. Research also demonstrates that diverse schools are better equipped than high-poverty schools to counteract the negative effects of poverty.” Moreover, in their book, Kahlenberg and Potter emphasize the importance of maintaining a focus on integration in education form; they quote Albert Shanker, founder of the charter school movement, saying, “children from socioeconomically deprived families do better academically when they are integrated with children of higher socioeconomic status and better-educated families,” and “when children converse, they learn from each other. Placing a child with a large vocabulary next to one with a smaller vocabulary can provide a gain to one without a loss to the other.” They critique the recently popular charter school movement for moving away from this vision. Magnet schools, on the other hand, have maintained the goal of racial integration, so it is important to better understand why certain schools are more successful at this than others.

On the other hand, frustrated parents argue that the focus on integration forces schools to put their resources into attracting students from whiter, wealthier towns. In order to uphold a “racially balanced” school, magnet school lotteries must give preference to applications from towns with greater white populations rather than to the areas heavily populated by minority students who have a far greater need for good schools. Darien Franco, 2011 graduate of Capital Preparatory Magnet School told me, “I think that the desegregation goal is a bit superficial because what I assume is the whole point is part of an effort to make sure everyone’s getting a similar, quality education. I think whoever wants/needs a spot the most should get it. Of course Hartford schools are going to have a high percentage of black/Latino kids, because that’s who lives in Hartford. I don’t see exactly how sending in non-black/Latino children to a school alleviates any particular issue, other than they’ll be more used to seeing them in everyday life.” Proponents of the charter school movement agree; charter schools tend to be very segregated with almost entirely minority students in order to serve the most at-risk students.

As a result of Sheff v. O’Neill, in the past ten years, the state has spent $1.4 billion to renovate and build new magnet schools, which are designed as reduced isolation schools that draw students from the city and suburbs. Magnet schools in the Hartford area have special themes designed to draw in students from both the city and suburbs, and they are required to have a student body that is 25%-75% racial minority students (newly defined as African American or Hispanic/Latino) in order to be funded by the state. They are also designed to have a 50-50 balance of Hartford and suburban students. While magnet schools are public schools open to all residents of Connecticut and appear to select students randomly based on a lottery, in truth, there are many subtle factors determining which students end up at different schools. Magnet schools have incentives to be academically successful and are required to maintain a racial balance, so they are never truly random in their selection of students.

One important factor in attracting a certain student body is the way schools communicate with parents and prospective students. In a seminar at Wesleyan University called “Choice: A Case Study in Education and Entrepreneurship,” students visited various “choice” school fairs and open houses. Our class observed many schools present themselves to parents and children in order to better understand how they choose to communicate. However, from the field notes collected at the school fairs and open houses we visited, racial and socioeconomic integration were rarely mentioned. School representatives rarely brought up integration or provided information on their school’s demographic statistics or goals, and parents did not usually ask about it either. This is not because race and socioeconomic status don’t matter anymore; on the contrary, there is still a great deal of variation in racial balance even in Connecticut choice schools. It seems ironic that racial balance is rarely discussed at magnet school fairs and open houses, when it is the fundamental purpose of magnet schools and is required for the schools to be funded. Schools and parents are not actively discussing diversity and racial balance in schools, but there are clearly unspoken factors influencing the wide discrepancies in the percentage of minority students we observe among Hartford-area magnet schools.

Unwrapping Hartford magnet school demographics

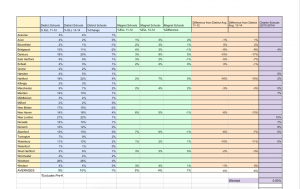

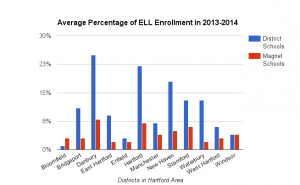

The fact that there is little transparency or emphasis on racial balance in schools does not mean demographic factors are unrelated to parents’ choice of schools for their children. In their field notes from the Regional School Choice Office (RSCO) fair on February 7, 2015, Alix Liss and Sara Guernsey observe that “despite the fair being particularly minority heavy in attendance, the individuals looking at the specialized schools, whether performing arts or science based, were predominantly white.” Does this hold true for actually enrollment in magnet schools? In order to find out, I assigned a theme to each Hartford-area magnet school and analyzed the demographics of each category. In order to create my categories, I drew on a list compiled by Mira Debs and Jack Dougherty, and looked at the website and mission statement of each school. Though some schools have more than one theme, for the sake of this analysis, I chose the theme I thought was most prominent. I have divided the schools into the following categories: STEM, college prep, career prep, alternative pedagogy, arts, global/international studies, liberal arts, character education, and early childhood only. Using data from the 2014-2015 CSDE Sheff Compliance report from October 1, 2014, I calculated the weighted average percent of black/Latino students in each category. I found that large differences in demographics do exist among these schools. The following table shows all of the Hartford-area magnet schools, categories, and demographic data, including average percent of black/Latino students and average percent of students from Hartford, weighted based on the size of each school.

Table 1: Hartford-Area Magnet Schools, themes, and 2014-2015 demographic data. Demographic data compiled from CSDE Sheff Compliance Report.

The categories with the highest percentage of minority students were character education* (78.9%), college prep (74.4%), and career prep (71.1%), while the categories with the lowest percentage of minority students were early childhood* (54.3%), STEM (57.4%), arts (61.0%), and liberal arts* (62.3%) (I have marked categories with only one or two schools with an asterisk here and later in this essay; all other categories have at least four schools). The following graph shows these percentages.

Figure 1: Average percent black/Latino students in Hartford-area magnets schools by theme

The observation at the RSCO fair that white families migrated toward the more niche-themed schools makes sense considering the actual enrollment in these schools (although, it is interesting to observe that they cited those families as “predominantly white” even though the schools with the highest percentage of non-minority students are still all over 50% black and Latino). Of course, this data cannot explain whether the reason for these demographic differences is that certain types of schools appeal to certain demographics or that these schools are actively marketing to different demographics due to their philosophies or institutional goals.

However, one way schools might alter their applicant pool is through the location of their school. Because transportation is an issue for many parents and busing for interdistrict schools can be quite complicated and time-consuming, a school far outside the city in the suburbs may be less accessible to many families. In fact, using data on the number of Hartford resident students in each magnet school from the 2014-2015 CSDE Sheff Compliance Report, I calculated that magnet schools located in the city of Hartford have an average of 43.7% Hartford resident students enrolled, while only 34.1% of students are Hartford residents in schools located outside of Hartford (in towns such as East Hartford, Bloomfield, Avon, Enfield, Glastonbury, New Britain, Manchester, Rocky Hill, South Windsor, and West Hartford).

Creating a 50-50 balance of Hartford and suburban students is a main goal of magnet schools because Hartford is the second poorest city in the country, and the vast majority of Hartford is black or Latino, with only 15.8% of the city’s population whites of non-Latino background in the 2010 census. This caused the extreme segregation of Hartford public schools that fueled the Sheff movement. For race, though, the difference between magnet schools in Hartford and the suburbs is much less: schools in Hartford are on average 65.8% black/Latino, while schools located outside of the city are 62.7% black/Latino. Though a difference still exists, the fact that the numbers are pretty close probably indicates that schools located in the suburbs likely enroll more suburban black/Latino students than schools in Hartford. The following interactive map shows the location of Hartford-area magnet schools and their percentage of minority students:

Direct link to the map above

Another possible explanation is that many of Hartford’s suburbs also have a high percentage of racial minorities. However, when comparing demographics of magnet schools to the demographics of the suburbs in which they are located, there doesn’t appear to be much of a difference. I looked at the demographics of the three suburbs that have more than one magnet school: Avon, East Hartford, and Bloomfield. Though these three suburbs have highly different demographics (Avon is .98% black and 1.57% Latino, East Hartford is 18.83% black and 15.23% Latino, and Bloomfield is 66.06% black and 3.67% Latino), their magnet schools’ average minority populations are 64.6%, 60.2%, and 62.7% respectively, which does not reflect the differences in the towns’ populations.

Based on my analysis, I can conclude that theme of the school is more important than school location in determining the racial demographics of schools. However, when looking at the percentage of Hartford students in each school, location is much more important. Theme may be important too; looking at the table above, we can see that the themes with the highest percentage of minority students, character education*, college prep, and career prep, enroll 48.5%, 43.5%, and 43.1% Hartford students, respectively, while the themes with the lowest percentage of minority students, early childhood*, STEM, and arts, enroll 24.8%, 35.7%, and 39.4% Hartford students respectively (weighted averages based on total school enrollment). But the themes do not follow the exact same order in terms of their Hartford student population as they do minority student population.

Since location does seem to affect demographics at least to some degree, do schools with themes that enroll fewer minority students and fewer Hartford students tend to locate themselves further outside the city? In order to answer this question, I compiled the addresses of each magnet schools and used Google Maps to calculate their distance from Hartford (I used the location point that Google Maps automatically associates with “Hartford, CT,” which is in the center of the city, so even schools located in Hartford have a “distance from Hartford” that is based on this common centerpoint).

Table 2: Hartford-Area Magnet Schools, locations, and 2014-2015 demographic data. Demographic data compiled from CSDE Sheff Compliance Report.

Based on this analysis, there is not an obvious correlation between school location, theme, and demographics. For example, STEM schools, which on average enroll only 55.8% minority and 34.6% Hartford resident students, are only 4.3 miles from Hartford center, on average. On the other hand, career prep schools, which on average enroll 77.0% minority and 51.2% Hartford resident students, are 6.7 miles from Hartford center, on average. Therefore, there is no clear indication that different themed schools are choosing their location based on the type of students they attract or wish to attract. Of course, this analysis is limited in that it is based on a small number of schools and does not take into account the demographics of different suburbs. Moreover, because many magnet schools were founded relatively recently, many schools have changed location in the past few years or are currently in temporary locations while permanent sites are built.

In conclusion, though school representatives and parents rarely talk about demographics, there are clearly many factors that affect racial composition of schools. In this analysis, I found that theme is a key indicator, while location also has a smaller influence. Further analysis would be necessary to understand why theme affects the racial balance of schools. Clearly, though, as schools develop their themes in order to attract students from Hartford and its suburbs, it is important to keep in mind how different themes relate to school demographics.