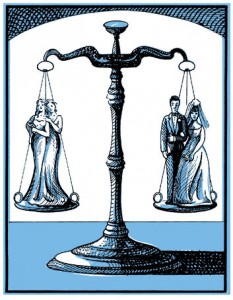

Marriage Equality and Religious Liberty

On June 26, after months of robust public debate, two full days of oral argument, and blanket media coverage, the Supreme Court issued opinions in two same-sex marriage cases, Hollingsworth v. Perry and U.S. v. Windsor. The cases generated a record 156 amicus curiae (friend of the court) briefs, of which more than 30 were filed by a broad array of religious and faith-based organizations.

On June 26, after months of robust public debate, two full days of oral argument, and blanket media coverage, the Supreme Court issued opinions in two same-sex marriage cases, Hollingsworth v. Perry and U.S. v. Windsor. The cases generated a record 156 amicus curiae (friend of the court) briefs, of which more than 30 were filed by a broad array of religious and faith-based organizations.

The religious briefs included as signatories, among others: the Becket Foundation for Religious Liberty, Catholics for the Common Good, the National Association of Evangelicals, the Southern Baptist Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of America, the Thomas More Law Center, the Family Research Council, the United States Council of Catholic Bishops, the American Humanist Association, the American Jewish Committee, the Bishops of the Episcopal Church (11 states), the Anti-Defamation League, and the California Council of Churches. Not to mention the Westboro Baptist Church.

In other words, it’s fair to say that most of the organized American religious world expressed its opinion on same-sex marriage to the court. But was the court listening?

There is little evidence to suggest that this avalanche of amicus submissions affected the justices in either case. A review of the citations to legal briefs in the court’s opinions reveals that no references were made to any of the legal briefs filed by religious organizations.

The lack of impact can be explained in part by the fact that Hollingsworth v. Perry, which mounted a direct constitutional challenge to California’s ban on same-sex marriage, was not decided on the merits. Instead, the Court determined that Dennis Hollingsworth, the Republican state senator who represented supporters of the ban, did not have standing to bring the case before the Court. As a result, the Court gave no indication of how it might have incorporated the legal arguments about the constitutional status of bans on same-sex marriage presented in the 96 amicus briefs filed in the case, including those of the religious organizations.

The Court did, however, address the merits in U.S. v. Windsor, which involved the claim of 84-year-old Edith Windsor that Section 3 of the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) denied her the right to be exempt from paying income taxes on the inheritance left to her by her same-sex spouse of 40 years. Windsor’s contention was that by preventing legally married same-sex couples from receiving federal benefits, DOMA was discriminatory and should be found unconstitutional.

Although the Windsor case did not require the Court to reach a conclusion about the constitutional status of same-sex marriage per se, in a close 5-4 decision authored by Justice Anthony Kennedy, DOMA was found to be unconstitutional because it violates the equal protection and due process rights guaranteed to all by the Constitution. According to Justice Kennedy, “DOMA’s avowed purpose and practical effect are to impose a disadvantage, a separate status, and so a stigma upon all who enter into same-sex marriages made lawful by the unquestioned the authority of the states, and the principal effect is to identify and make unequal a subset of state-sanctioned marriages.”

Kennedy went on to say, “What has been explained to this point should more than suffice to establish that the principal purpose and the necessary effect of this law are to demean those persons who are in a lawful same-sex marriage.” He concluded that the court was therefore required “to hold, as it now does, that Section 3 of DOMA is unconstitutional as a deprivation of the liberty of the person protected by the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution.”

In a dramatic victory for Edith Windsor and the opponents of DOMA, the court’s majority thus established that same-sex couples are entitled to all federal benefits that previously had been withheld from them. But it is important to emphasize that the court did not engage the arguments made by religious organizations and faith groups in their amicus briefs concerning the question of whether same-sex marriage is a fundamental constitutional right. In Windsor as in Perry, neither the majority nor the dissenters referenced those briefs even though Justice Scalia’s opinion in the Windsor case certainly coincides with views expressed by many of religious groups who argued that DOMA should be sustained.

Tempting as it may be to dismiss the amicus briefs filed by faith groups and their affiliates in these cases as little more than public relations exercises, in fact they establish the battle lines in a war over constitutional rights that will be fought over a series of upcoming cases, including the contentious contraception mandate of the Affordable Care Act.

Those on the conservative side—including the Becket Foundation, the National Association of Evangelicals, the Southern Baptist Convention, and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—contend in the Perry case that California’s Proposition 8 referendum banning same-sex marriage was properly enacted by a democratic majority; that the state of California has a legitimate interest in reserving marriage to heterosexuals; that the charge that Proposition 8 supporters are animated by bigotry or hate is false; that heterosexual marriage as the foundation of society; and that the state has the power to base laws on religious and moral teaching.

But the crux of their argument lies elsewhere—with religious liberty. It is most clearly laid out in the double-barreled Becket brief, which covers both cases in 188 pages.

The same-sex marriage debate, the brief begins, is “best resolved not by judicial decree, but by the legislative process, which is more adept at balancing societal interests, including religious liberty.” What follows is an elaborate exploration of the ways in which religious liberty will be imperiled if the court finds California’s ban on same-sex marriage to be unconstitutional.

Religious institutions and individuals that object “will face an increased risk of lawsuits under federal, state, and local anti-discrimination laws, subjecting religious organizations to substantial civil liability if they chose to practice their religious beliefs.” Moreover, “religious institutions and individuals will face a range of penalties from federal state and local government, such as denial of access to public facilities, loss of accreditation and licensing, and the targeted withdrawal of government contract and benefits.”

The bottom line: “These foreseeable conflicts implicate the fundamental First Amendment rights of religious institutions, including the rights of freedom of religion and freedom of association.” Those individuals and institutions that have “conscientious objections” to same-sex marriage thus face threats to their religious liberty from public accommodation laws, public housing laws, and employment discrimination laws.

The anti-discrimination laws discrimination will, Becket asserts, open up new avenues of civil liability because a court decision cannot carve out the kinds of exemptions than only a legislature acting on these matters can properly address. For that reason, the courts should not decide the issue.

With respect to the penalties that state and local governments might apply to religious dissenters, Becket anticipates exclusion from government facilities and forums, loss of licenses or accreditation, disqualification from government grants and contracts, loss of state and local tax exemptions, and loss of educational and employment opportunities. To support this argument, the brief includes a 101-page index with supporting evidence for each category and applicable state laws.

But what about Employment Division v. Smith, the 1990 decision that declared that “neutral and generally applicable laws” could not be challenged as violations of the First Amendment’s protection of religious liberty? Wouldn’t that render same-sex marriage proof against religious liberty claims?

To the contrary, Becket argues, Smith “specifically invited states to consider protections for religious activity that go beyond what the Free Exercise Clause protects.” It was therefore rational for California voters to enact Proposition 8 as a means of doing so.

Becket closes by urging the court not to strike down Proposition 8 and DOMA but instead leave same-sex marriage to legislatures—the only institutions fully capable of “arriving at workable compromises regarding religious liberty.” Only then will the justices avoid generating another irreconcilable conflict as they did by “freezing the debate” over abortion in 1973 with Roe v. Wade, which has generated litigation ever since.

Common claims are also made on the liberal side, in the briefs of such organizations as the Anti-Defamation League, the American Jewish Committee, and the American Humanist Association. These sketch a history of society’s changing views of same-sex marriage, insist on a fully secular reading of the Constitution, and use the 14th Amendment’s guarantees of equal protection and due process to argue for a right to same-sex marriage.

Most importantly, several of the briefs directly address the religious liberty arguments made by Becket.

Stating that it is “principally devoted to the serious issues of religious liberty that arise in the wake of same-sex marriages,” the American Jewish Committee (AJC) brief by Marc Stern, Douglas Laycock, and Thomas Berg rejects the idea of prohibiting same-sex marriage in order to protect religious liberty because in their view “[n]o one can have a right to deprive others of their important liberty as a prophylactic means of protecting his own.”

“The proper response to the mostly avoidable conflict between gay rights and religious liberty is to protect the liberty of both sides,” the AJC argues, going on to remind the court of the “doctrinal tools available to protect religious liberty with respect to marriage,” including the “ministerial exception established” last year in Hosanna-Tabor v. EEOC that prevents the government from “’interfer[ing] with an internal church decision that affects the faith and mission of the church itself.’”

Recognizing that conflicts with anti-discrimination laws can arise when religious organizations offer services to the general public and engage in “external” aspects of their mission, the AJC then explores the meaning of the “neutral and generally applicable” rule created in Employment Division v. Smith. If, for example, an anti-discrimination law provides for secular exceptions, similar exceptions must be made for religious conscience claims of individuals or organizations.

Moreover, the AJC argues, should the Defense of Marriage Act be overturned, the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act “will protect against any substantial burdens imposed on religious liberty.” The brief concludes by recommending that in an appropriate future case “the Court should be open to reconsidering the rule announced in Employment Division v. Smith” to clarify the issues associated with religious objections to same-sex marriage.

Taking a different approach to the issues raised by Becket and other conservative faith groups, the amicus brief submitted by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) emphasizes the way in which justifications rooted in religious and moral disapproval have resulted in discriminatory treatment of minority groups. The ADL maintains that slavery, segregation, and bans on interracial marriage have all been repudiated because “[r]eligious justifications for discriminatory laws vanish as popular support for those forms of discrimination fade.”

In addition, the ADL contends that as public opinion and attitudes change, “this Court no longer relies on religious and moral disapproval alone to uphold laws, particularly laws burdening minority groups.” As evidence, the brief points out that Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion in Lawrence v. Texas (2003), which struck down a Texas law that criminalized same-sex sodomy, relied in part on the principle that the “[g]overnment may not act against a particular group based solely on a majority’s view of what morality or religion commands” [emphasis in the original].

The court thus “reaffirmed an essential constitutional principle: that enforcing majoritarian morals, standing alone, offers no rational basis for a law that disfavors unpopular groups.” For that reason, “the religious and morality based arguments advanced by the Petitioner’s amici in the same-sex marriage cases lack persuasive power.”

Finally, the ADL turns to religious freedom:

No matter how framed, the religious freedom argument can gain no traction in a case, like this one, involving a challenge to a discriminatory law; this Court is not in the habit of upholding discriminatory laws to protect religious prerogatives. Amici would do better to recognize that religious liberty is best safeguarded when religious groups retain the freedom to define religious marriage for themselves, remembering that civil marriage is an institution of the government, which is prohibited from establishing laws reflecting particular religious viewpoints” [emphasis in original].

According to the ADL, in other words, religious freedom can only be protected if no particular view of religious marriage is enshrined in government policy and civil law, as would be the case if the Court upheld Proposition 8’s limitation of marriage to heterosexuals.

The arguments about religious freedom proffered by the various amici in the same-sex marriage cases received little attention from the news media prior to the Court’s decision in June. What’s important to recognize is that the same arguments will be front and center in cases now making their way onto the Court’s docket.

As the ADL made clear, the old morality-based arguments deployed by religious advocacy groups in the past were refuted by Justice Kennedy in Lawrence v. Texas and so no longer constitute credible legal discourse—as Justice Antonin Scalia acknowledged by writing, in his Lawrence dissent, that the decision “effectively decrees the end of all morals legislation.”

Conservative religious advocacy groups have thus been deprived of one of their most potent lines of argument in cases that pit the rights of religious believers against the claims of those who assert that the very exercise of those rights constitutes discrimination. It is for that reason that several of the more seasoned conservative religious advocacy groups have pivoted to the religious freedom argument.

To the extent that arguments about discrimination can be turned into arguments about the religious freedom of those who are accused of doing the discriminating, the court will be called upon to do something very different from weighing the strength of particular, religiously based moral claims.

When Becket argues that the recognition of same-sex marriage threatens the religious liberty of sectarian organizations and individual believers, it challenges the court to decide whether same-sex couples or religious believers have a stronger constitutional claim. Looking ahead, it is clear that the meaning of religious liberty will frame the arguments of some of the most important matters coming before the Court, most notably the contraception mandate in the Affordable Care Act, which requires businesses and non-profit organizations to include contraceptive coverage for female employees.

Not surprisingly, Becket is spearheading efforts to challenge this provision, claiming that the mandate violates the religious liberty of both business owners and non-profit organizations that oppose contraception on religious grounds. Becket has brought suit on behalf of a variety of Catholic organizations and is seeking class action status for them.

As of now, two federal appeals courts have issued contradictory rulings on the question of whether for-profit, secular companies can avoid the mandate by way of the Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Meanwhile, the federal government has filed a petition asking the justices to resolve the question.

“I think it’s likely the Supreme Court is going to end up deciding this thing,” Mark Rienzi, Becket’s senior counsel for Becket, told The Hill in August. There’s every reason to think he’s right.