West Hartford Science Walking Tour: Golf Acres/Aiken District

Start at 333 North Steele Road

Suzanne Corkin

Suzanne Corkin (née Hammond) was born at Hartford Hospital and was an only child. Dr. Corkin grew up in West Hartford, directly across the street from William Scoville, at 333 North Steele Rd, and was best friends with his daughter, Alison Scoville Dittrich. The two went to school together from third grade until college and stayed very close after that. Dr. Corkin went to the Oxford School in West Hartford. She went to college at Smith College and then received her PhD from McGill University. While there, she read an article about Henry Molaison. Mr. Molaison received psychosurgery at Hartford Hospital to relieve seizures and was left with a profound memory deficit. You can learn more about him and the surgery here. Her dissertation advisor, Brenda Milner, asked if she would like to work with him. Her dissertation was entitled “Somesthetic function after focal cerebral damage” which examined Mr. Molaison’s sense of touch. In 1964 she began working at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the lab of Hans-Lukas Teuber. When he died, she became the director of the lab. She devoted her career to working with Mr. Molaison and to studying how human memory works and the brain substrates of memory in a variety of populations. She discovered that Mr. Molaison had profound short-term memory loss. He could remember very little from after the time of the surgery for the rest of his life. According to Dr. Corkin: If you talked to him in the afternoon and said, “Have you had lunch?,” he would say, “I don’t know” or “I guess so,” but he would not remember what he had had. And if you asked, “What was your last meal?,” he wouldn’t know what it was.

She was an early user of functional imaging like MRI and fMRI to help understand how memory works. She published over 150 research articles and was author or co-author of 10 books. She received a MERIT award from the National Institutes of Health and the Baltes Distinguished Research Achievement Award from the American Psychological Association, Division on Aging. She also became a committed advocate for increasing women in science, giving talks on the topic, and received the Brain and Cognitive Sciences Undergraduate Advising Award at MIT. After her death, a group of former students published this tribute to her.

We were fortunate to have Dr. Corkin speak at Trinity College. You can watch the full talk here “The Amnesic Patient HM: A Half Century of Learning About Memory.”

Here is a clip where she talks about whether Mr. Molaison has a sense of self.

After her death, Dr. Scoville’s grandson, Luke Dittrich wrote a book Patient H.M.: A Story of Memory, Madness, and Family Secrets. In it he claimed that Dr. Corkin tried to hide the existence of a lesion in the orbitofrontal lobe and that she shredded data to cover errors. This was refuted in a letter to the New York Times signed by over 200 scientists, and in the published work. In fact, she had published data that she claimed suggested an orbitofrontal lesion in 1983 (Eichenbaum et al., 1983).

Directly across the street at 334 North Steele Road was the home of William Beecher Scoville, the surgeon who performed the surgery on Mr. Molaison.

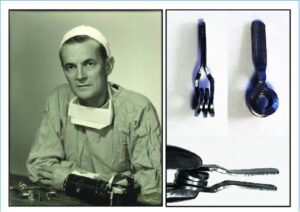

William Beecher Scoville

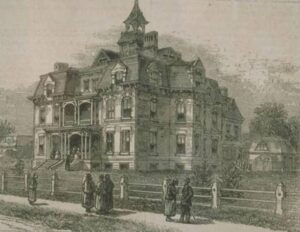

William Beecher Scoville established the Department of Neurosurgery at Hartford Hospital in 1939. William Beecher Scoville was a descendent of Harriet Beecher Stowe. He was born in Philadelphia in 1905 to Samuel and Katherine Gallaudet (Trumbull) Scoville. His mother was a descendant of Thomas Gallaudet. He attended Loomis School, received his undergraduate degree at Yale University and his medical degree at the University of Pennsylvania. His first wife was Emily Learned Scoville and they had three children that they raised at 334 North Steele Road in West Hartford, Barrett, Alison, and Peter. In 1941 he developed the first neurosurgery residency program in Connecticut. His students referred to him as “Wild Bill.” ‘Bill drove fast, lived hard and operated where angels feared to tread,” said Dr. David Crombie, former chief of surgery at Hartford Hospital who met Scoville in the early 1960s as an intern at the hospital and became friends with his son. Scoville’s wife had schizophrenia and this may have played a role in his desire to find surgical options for treating mental illnesses. In the book written by his grandson, Luke Dittrick, Dittrick speculates that Dr. Scoville may have actually performed surgery on his wife, Emily Learned Scoville.

Scoville’s aneurysm clip

In addition to the surgery on Mr. Molaison, Dr. Scoville is known for a coiled aneurysm clip that he invented. His second marriage was to Helene Deniau Scoville, with whom he had two children Sophie and William. Dr. Scoville’s brother was Rev. Gordon Scoville, the founding pastor of Westminster Presbyterian Church in West Hartford. Dr. Scoville had a life-long interest in cars and was known for driving his red Jaguar or motorcycle on Steele Road and tinkering with cars in his spare time. He was an early proponent for motorcycle helmets but never wore one himself. Scoville was killed in 1984, at the age of 78, when he backed up his car on the highway to get to an exit he had missed.

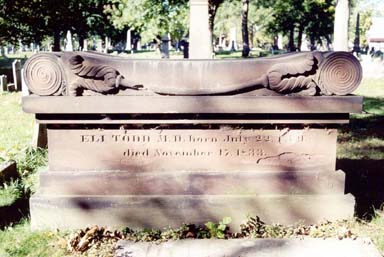

On the NW corner (what is now 777 Prospect) is where Yung Wing’s house once stood. You can learn more about him by using the Cedar Hill Cemetery information-dial (860) 760-9979 and press #21,

On the NW corner (what is now 777 Prospect) is where Yung Wing’s house once stood. You can learn more about him by using the Cedar Hill Cemetery information-dial (860) 760-9979 and press #21,

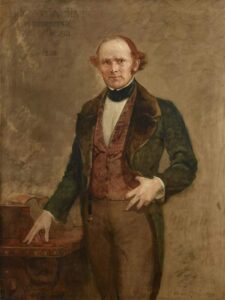

If you head back to Main Street and head north, at 805 Main Street you will find the plaque across the street from the Old Statehouse that marks the location of Horace Wells’ dental office. The plaque was created by Enoch Woods. It has a profile of Wells with the inscription, “To the memory of Horace Wells Dentist who upon this spot DECEMBER 11 1844 submitted to a surgical operation DISCOVERED demonstrated and proclaimed the blessings of ANESTHESIA.”

If you head back to Main Street and head north, at 805 Main Street you will find the plaque across the street from the Old Statehouse that marks the location of Horace Wells’ dental office. The plaque was created by Enoch Woods. It has a profile of Wells with the inscription, “To the memory of Horace Wells Dentist who upon this spot DECEMBER 11 1844 submitted to a surgical operation DISCOVERED demonstrated and proclaimed the blessings of ANESTHESIA.” At 675 Main Street you can find a Wells stained glass window in Center Church, where Horace and his wife were members. Inscriptions on the window read “Neither shall there be any more pain for the former things are passed away” and “In memoriam Horace Wells the Discoverer of Anesthesia and his wife Elizabeth Wales Wells.”

At 675 Main Street you can find a Wells stained glass window in Center Church, where Horace and his wife were members. Inscriptions on the window read “Neither shall there be any more pain for the former things are passed away” and “In memoriam Horace Wells the Discoverer of Anesthesia and his wife Elizabeth Wales Wells.” Then turn right on Steel and visit the Connecticut Science Center. Check out their Sight and Sound exhibit and test the helmets in their Sports Lab.

Then turn right on Steel and visit the Connecticut Science Center. Check out their Sight and Sound exhibit and test the helmets in their Sports Lab.