Notopoulos on Yeats

[Posted by Alanna Lynch ’14, for Prof. David Rosen’s course, “Modern Poetry”]

When I went to the Watkinson Library to research W.B. Yeats for my modern poetry class, I expected to find some particularly rare manuscript of one of his more famous works, or maybe a signed copy of one of his books. What I left with was an essay written by one of Trinity College’s own Professors from a Classics magazine published in 1945. That’s not to say that the Watkinson didn’t have what I was initially looking for, because it did. But I chose that particular article for a reason – for exactly how unexpected it was. Being written a former Trinity Professor for a magazine that focused on Greek and Roman studies, the essay gave a unique perspective to one of Yeats’ most well-known poems, “Sailing to Byzantium.”

When I went to the Watkinson Library to research W.B. Yeats for my modern poetry class, I expected to find some particularly rare manuscript of one of his more famous works, or maybe a signed copy of one of his books. What I left with was an essay written by one of Trinity College’s own Professors from a Classics magazine published in 1945. That’s not to say that the Watkinson didn’t have what I was initially looking for, because it did. But I chose that particular article for a reason – for exactly how unexpected it was. Being written a former Trinity Professor for a magazine that focused on Greek and Roman studies, the essay gave a unique perspective to one of Yeats’ most well-known poems, “Sailing to Byzantium.”

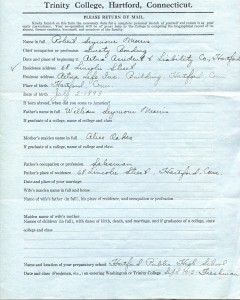

James A. Notopoulos, the essay’s author, taught at Trinity College from 1936 until his death 1967, and was a member of the Classics Department as well as the Hobart Professor of Classical Languages. The Classical Journal, an academic journal published by the Classical Association of the Middle West and the South (an organization founded at the University of Chicago in 1905) since 1905, featured his article in November, 1945. The Classical Journal typically contains articles on Greek and Latin literature, language, and studies in general, in addition to book reviews.

The fact that an article could be written about a piece of modernist poetry by a classics professor and subsequently published in a journal devoted to Classical studies speaks a lot to how the poem was received. The article was published almost two decades after “Sailing to Byzantium” was written and nearly a decade after the author’s death – this speaks to how influential Yeats was, that his works continued to be relevant to those outside the world of literature years after they were published. It also shows Yeats’ strong relation to his history and his influences; Yeats had a tendency to focus on mythological and biblical subjects, often tying what he experienced in the modern world with the past. His connections to this time period were not only recognized, but studied by experts of the Classics and considered important enough to impact the field of Greek and Latin studies.

The article itself contains several passages written entirely in different languages, one of which is in Latin, the other what I believe is ancient Greek. Although the article has many notes attached to the end, no translations are offered, only references to the works from which to quotes were taken. Clearly the article was meant to be read only by those that studied those languages and the books the passages were quoted from. This points to an attitude of exclusivity that was common among modernist poets – i.e. that their poetry should be read only by well-educated people. While it may be that Notopoulos didn’t offer any translation because he presumed that readers of The Classical Journal would be familiar with the classical languages, it is also possible that this trend of exclusivity in modern poetry bled into other fields as well. Ironically, Yeats was not nearly as obscure in his poetry as other modernists, like Eliot and Pound, and (as far as I can remember) wrote his poems completely in English.

The article written by Notopoulos begins by stating that “Sailing to Byzantium” is a “note-worthy” Platonic lyric. He cites Yeats’ friendship with Stephen Mackenna (a translator of Plotinus and noted prose-writer) and interest in both Plato and Plotinus as giving the author inspiration for the poem. When Notopoulos speaks of a “platonic mood” or “platonic lyric” what he means is that Yeats is drawing on the Platonic theory of forms. Plato believed that the reality humans perceive is not in fact that true reality – that what we experience in our daily lives are only copies of the true or ideal forms that exist elsewhere. Everything in the world is only a copy of these true forms, and Plato’s ultimate desire is to reach the plane of ideal forms, which are both eternal and perfect. Notopoulos argues that when Yeats speaks of “the artifice of eternity,” what he means is the world of ideal forms described by Plato. Notopoulos then goes on to described what might consist of Yeats’ ideal world, drawing on experiences Yeats wrote about in his travels to Italy at the end of his life.

The article that I found at the Watkinson offers interesting insight into not only Yeats’ poetry, but the general impact it had on other areas of study. Notopoulos uses his knowledge of Greek and Roman studies to develop a different interpretation of “Sailing to Byzantium.” He reflects both on how Yeats was influenced by Byzantine art and how he interpreted it. My favorite aspect of the article, however, was the conclusion Notopoulos came to at the end of his essay with a quote from Percy Bysshe Shelley; that “‘Poets… are a very chameleonic race; they take the color not only of what they feed on, but of the very leaves under which they pass.’”