By: Duncan F. McN. Grimm (History major, Class of 2015)

This past Thursday, October 4, Professor Jeffrey Jackson of Rhodes College delivered an informative and engrossing lecture on the flooding of Paris during the frigid winter of 1910. An event lesser known by the intellectual and commoner alike, Jackson further highlighted that this landmark event often becomes eclipsed by the volatile political climate of 20th century France, as well as the two subsequent devastating World Wars. Possibly because of its close temporal proximity to the Great War, some historians wonder if the common suffering and eventual surmounting of the flood led to a convergence transcending politics and social classes that enabled citizens of France to act similarly in the trauma of 1914-1918. Regardless of whether the two disaster-reactions are related or not, the fact remains that intensely divided citizens came together in a time of great danger to themselves and their city to help one another survive. Jackson examines through narrating Paris’ strife how this happened.

The annual rising of the Seine River, along with the rains were initially no concern to many Frenchmen, so it is not a surprise that when the waters were rushing at 15 miles per hour and in places upwards of 20 feet above normal, that Paris was stunned. The situation demanded action.

Engineers working along side the police, military, and other “first responders,” to construct wooden walkways above the water for people to travel. Three of the below images show what lengths engineers went to ensure Paris could still function, and not descend into anarchy. Because of the water many of the newest technologies, including the subway system, were unusable. For a time, anachronistic standbys like horse drawn carriages and gas lighting were reignited during this period of darkness. Interestingly enough, the rising of the water led many to question their newfound faith in science and progress.

Although the social fabric frayed, society did not fall apart. Despite the remaining political and social divisions, according to Professor Jackson the flood provided a moment of solidarity out of necessity, allowing the culture to deepen its myth of national unity, and to provide a foundational memory of common strife to build upon later. In hindsight, this hardship could be viewed as a dress rehearsal for the turmoil and public reaction to the effects of World War I. Overall, the survival of the flood through human ingenuity and teamwork led to a new sense of optimism, a mental momentary denial of past grievances, and a general positive attitude of individuals towards their fellow man.

Oddly enough, in the immediate aftermath of the flood, church and state worked together. The Red Cross opened shelters and temporary communities were constructed for individuals displaced by the flood waters. Because of this precedent, after the flood there was a stronger social safety net in place for future monumental catastrophes.

The language of fraternity of the French Revolution was rekindled, and a national story was written about the transcendence of the population and the strength of the individual in the face of previously unthinkable circumstances. The study of this natural disaster has the potential to remind us today of what it can take to bring an intensely polarized community together.

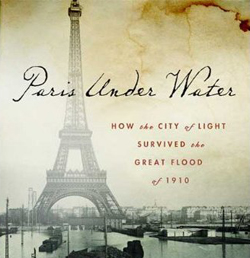

Professor Jackson’s book, Paris Under Water, is a collection of short stories and narratives of Parisians recounting the events of the Great Flood, and how they themselves dealt with the new city landscape. After the flood waters subsided, and man had battled nature and survived, individuals began to pick up the pieces, slowly becoming distanced from their work alongside others, only to be drawn together again in 1914.

There is definitely a strong case to be made not only for the ingenuity and strengthening of French culture during the flood, but also that their remembered bonds and triumph helped them to later endure four terrible years of war. Perhaps all cultures are in a similar state of expansion and contraction, pulling apart and coming back together in desperate times. Perhaps cultures collapse when they have gone too long without a commonality among every individual, and it is this cycle that keeps communities, cities, and countries afloat.

I agree with you wholeheartedly Duncan. Especially in regards to the irrelevance of whether the trying times brought on by the flood made France’s efforts in World War I do unified and effective. I think the more prevailing and dominant theme is on you touched on directly. The fact that the French people could, if need be, come together and work towards one goal.

However, I don’t think this trait is unique to France and its people. I believe that is something all human communities have deep thing them and is inherently there because for some reason, they all have chosen to live in that given area, and share much in many ways, due to this proximity. Or it could simply be the a amalgamation of individual instances when people realized they could help and should help. To an outsider that amalgamation could have the appearance of a well thought out organized effort, a unique capability of the French people, when in reality everyone just did their fair share.

Thanks for the comment!

Glad you found the article enjoyable. It is fascinating when a group of individuals working towards similar goals create the potential for an organized effort to grow. Usually we think of a system as being imposed (for better or for worse) upon a community after a leader realizes the benefits, not usually formed from the ground up from seemingly isolated events. However we choose to study this or any other events, your point is certainly very insightful.

-DFG