Rolling the Dice on Prospect Ave

Prospect Ave:

Source: Prospect Ave from Google Maps 4

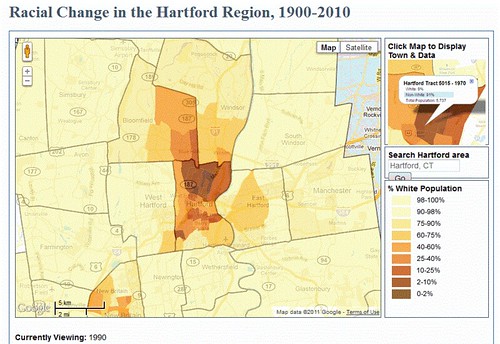

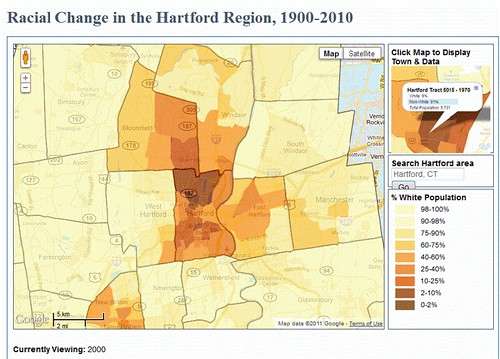

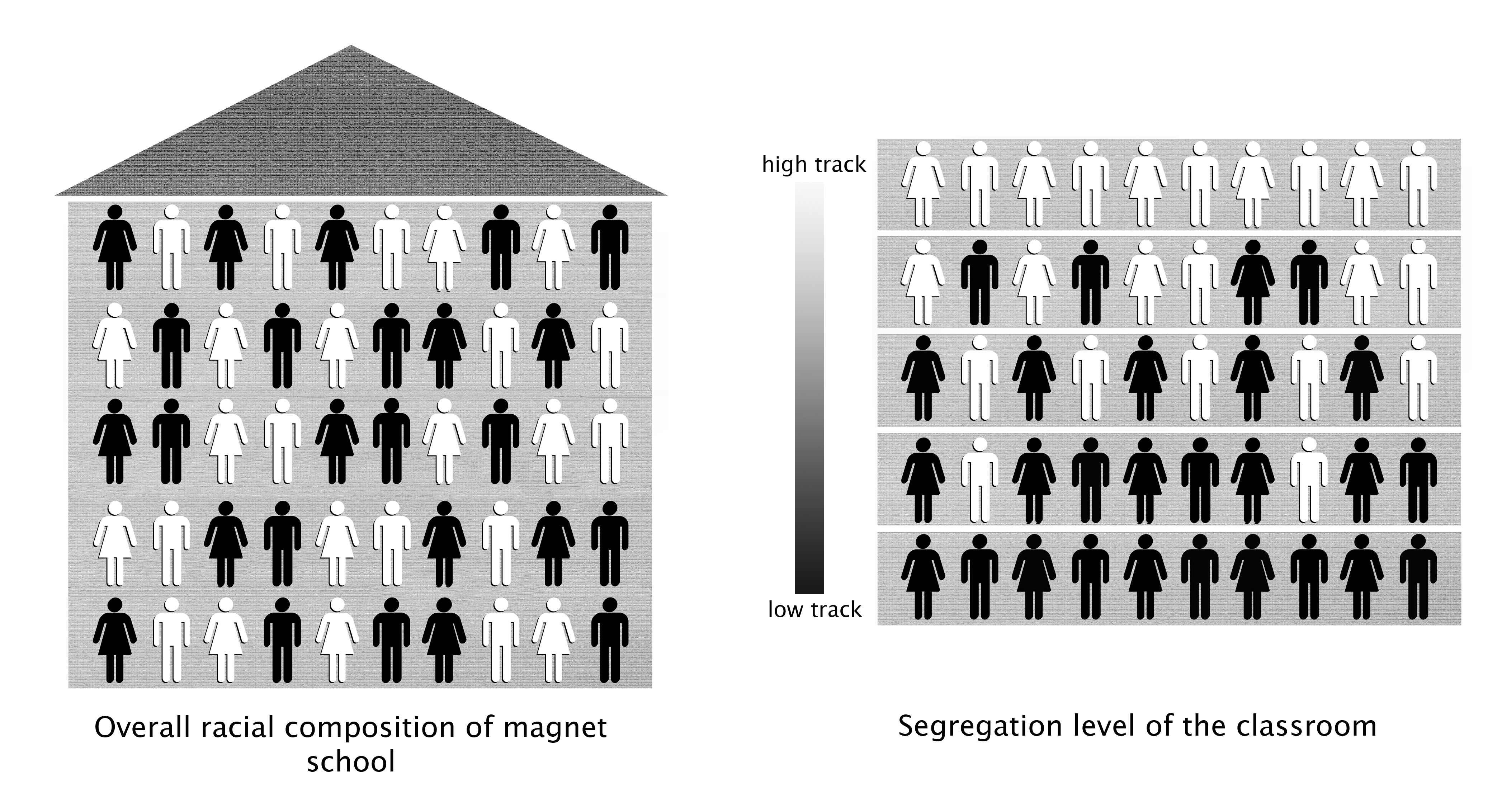

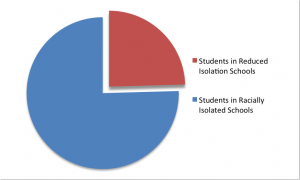

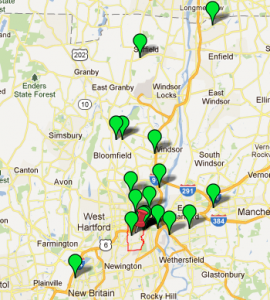

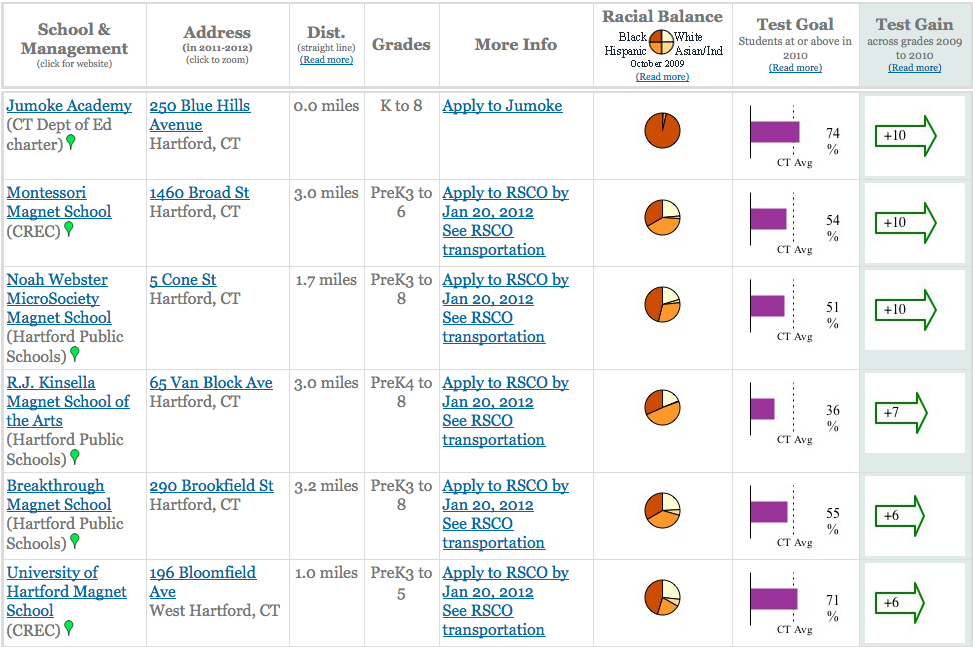

Prospect Ave is one of the main roads which connects Hartford and West Hartford and the specifoc differences in lifestyle between the odd numbered and even numbered houses will be the focal point of my argument. It is one of the original roads in CT and has been around since the time of redlining when many of Hartford’s minority residents began to trickle in. In the mid – late 1900’s, Prospect Ave was a landmark for where the suburbs ended and the ghettos formed due to redlining. It was this landmark that not only marked a severe change in housing and economic status but also in regards to the educational opportunity of the areas of Hartford and West Hartford. The left of the map consists of West Hartford public schools as well as the educational opportunity which comes along with the financial status of the area. On the right, Hartford public schools and educational inequality for those who were not blessed with the same financial opportunities.

Intro

The word segregation carries many different meanings for many different people. It is used mainly to describe the hardships and separations that minorities have faced and will face in the future. Today most people, however, don’t think of segregation having to do with educational opportunity. Within the past hundred years, Hartford Connecticut has gone through more change than almost any other city in the U.S. Hartford. One of the largest problems in Connecticut today is the achievement gap in education. The tricky part in getting people to pay attention to this problem is that to most people it is old news. Many policies have been implemented, money has been given to schools, and there is still a serious problem in Connecticut. In Connecticut the CMT or the Connecticut Mastery Test determines the standard for achievement. The CMT tests students in the areas of Mathematical reasoning, reading, writing, and science. I believe that this is incredibly important and deserving of a website due to the fact that it many people discuss the achievement gap in CT but disregard the massive discrepancy between the neighboring cities of Hartford and West Hartford. It is always important to look at the fine print in each study, and the fine print within the CT achievement data is the incongruity between West Hartford and Hartford, which has one of the lowest performances on the CMT.

Below is a sample question from the CMT online practice test as well as a link to the CMT full practice test:

Source: CMT Practice Test 1

The Hartford area is unlike any other area where at one point you can be in one of the poorest cities in America and within a 10-minute drive down the road be in one of the richest. Educational achievement gap is nothing new but the fact that when compared to low-income students from other states, Connecticut’s low-income students place in the bottom tier of achievement tests. This is due to the sole purpose of the cycle that has been created in Connecticut. Children who grow up in the impoverished areas especially Hartford don’t get the same experience out of their schooling due to their financial limitations. Due to these limitations in Hartford many youths either make it through high school to get a mediocre job, drop out before school ends, become affiliated with gangs, or worse. It is completely different when one lives in West Hartford. There is more money for education and therefore the children who live there or go to school there have a much higher chance of making it in the real world. I believe that there is a direct correlation between the achievement gap and the past racial inequality of the early 1900’s, the newer economic inequality of CT, and the educational inequality between Hartford and West Hartford in today’s society. Those points, along with the data from the national center of education statistics and the Connecticut counsel for educational reform I believe will be crucial in deciding why Hartford, CT has such a difference between its wealthy and poor in regards to education. In my opinion, the ridiculous discrepancy between low performers and high performers echoes the states ridiculous gap between wealthy and poor and between once segregated and non-segregated in Hartford. The gap between low income and high-income students in Connecticut is one of the highest in the U.S. Most people when they hear the words achievement or inequality automatically assume that the topic at hand is due to race. In the case of Connecticut, the gap began as a racial problem and has slowly evolved over the years into an economic one. This evolution has molded race and economic status into one determinant of educational outcome depending on how much money ones family makes, what race you are, and most importantly which side of Prospect Ave you were live on.

Prospect Ave Then:

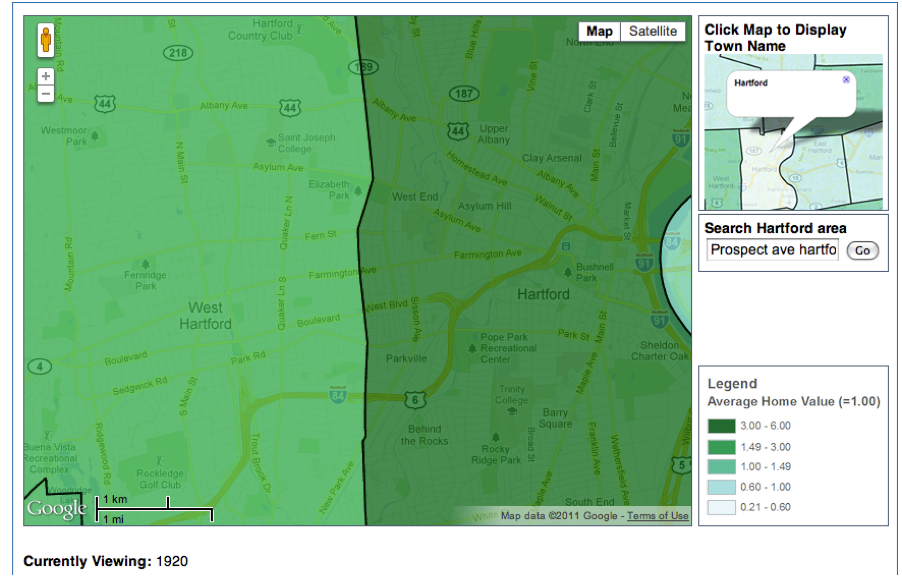

Source: Map of racial makeup on both sides of Prospect Ave from the year 1920. Maps provided by UConn Magic 3

Source: Map of racial makeup on both sides of Prospect Ave from the year 1920. Maps provided by UConn Magic 3

Above: Map of home value index on both sides of Prospect Ave from the year 1920. Map provided by UConn Magic 3

Above: Map of home value index on both sides of Prospect Ave from the year 1920. Map provided by UConn Magic 3

Since the abolition of slavery, minorities had been trickling up north for a chance at equal opportunity. “As the Reconstruction Era drew to a close, black-white relations came to be governed by the increasingly harsh realities of the Jim Crow system, a set of laws and informal expectations that subordinated blacks to whites in all areas of social and economic life”(American Apartheid, 9). These Jim Crow laws did not augment segregation, they simply regulated in which ways whites and blacks made contact. The main limitation Jim Crow laws helped to construct is the ghetto. The first ghettos were created in response to the overwhelming amount of minorities that occupied the north during industrialization. Since minorities were denied home ownership in white areas minority neighborhoods began to form. From the 1930’s on we begin to see the majority of barriers in housing begin to rise which would eventually lead to educational boundaries. It was at this time when “redlining” was born. The largest contribution in terms of educational opportunity from redlining was the beginning of the “suburbs”. The suburbs, at the time, were neighborhoods where whites could live without the worry of minorities moving in and as more blacks migrated to the north more whites moved out to the suburbs. Suburbs consisted of richer households, which provided more money to the state for their district and therefore had more prestigious schools to send their kids to. The decade went on and ended in suburban domination of economic status in West Hartford. For Hartford however, record unemployment, inflation, falling wages, increasing income inequality, and rising rates of black poverty continued to downgrade the educational opportunity of children. The ghetto had created the underclass, an area of economic non-sufficiency and educational mediocrity, which was nearly impossible to escape.

Prospect Ave Now:

Source: Map of racial change on both sides of Prospect Ave from the year 2010. Maps provided by UConn Magic 3

Source: Map of racial change on both sides of Prospect Ave from the year 2010. Maps provided by UConn Magic 3

Source: Map of home value index on both sides of Prospect Ave from the year 2010. Map provided by UConn Magic 3

Source: Map of home value index on both sides of Prospect Ave from the year 2010. Map provided by UConn Magic 3

Through the creation of ghettos and redlining however minorities were trapped into the low-income housing they are today in Hartford. Hartford has become one of the poorer areas and is mostly consistent of minorities whereas West Hartford has become one of the more well off cities in Connecticut. Hartford today, due to these constraints looks a lot different than it used to and its youth are paying the price. The only difference between then and now is that the reasons for inequality of schooling have shifted from racial to economic. Today families in Hartford cant afford supplies, books, or in some cases to even send their children to school. This is due to the economic constraints they have which were passed on from the racial constraints they once had as well.

The Story of Two Hypothetical Students

Enrique

To create the best argument for my example I will be using two hypothetical students: Enrique and Erik. Enrique is a boy from Hartford, CT. He is in the 8th grade and goes to a public school in the Hartford district. Him and his parents were born and raised in Hartford not far from Trinity College and have never left the state of Connecticut. Enrique’s father is in and out between multiple jobs but cannot seem to keep a stable one during these times of financial insecurity. His mother is working two jobs as both a caretaker during the day as well as a nighttime manager for a local restaurant. Enrique very recently took the CMT at his middle school and has just gotten the results back in the mail. Before we take a look at his scores I believe it is incredibly important that we take a look at the main characteristics of his district in order to decide whether or not Enrique was given the same opportunity of success as the students on the other side of Prospect Ave in West Hartford.

Even though the students are completely hypothetical cases the data that is being used to describe them is real.

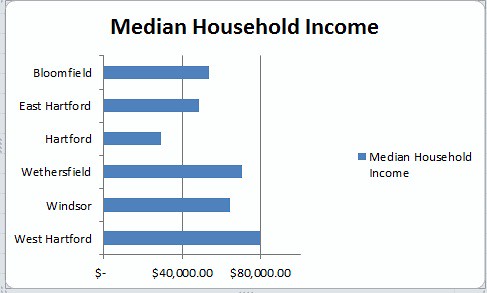

1. Economic:

Hartford is listed as one of the poorest areas in the state of Connecticut as of a 2009 study. The average family income is $28,300, which is $38,734 less than the state average of $67,034 and $50,188 less than the average family income in West Hartford. These economic troubles are a main reason for why the Hartford public school system and the families involved in it can’t afford supplies, books, or in some cases to even send their children to school. These economic hardships do not allow for children to have the possibilities of tutors and practice tests in order to get them ready for the CMT.

Source: Hartford CT Profile 6

2. Enrollment:

Source: State Deptartment of Education 8

Source: State Deptartment of Education 8

The enrollment in the Hartford public school district is just about 21,000 students, which is 11,000 more students than its neighboring West Hartford public school district. This is an important stat firstly, because it greatly throws off the student teacher ratio. Schools with a low student to teacher don’t allow kids the best chance to succeed due to the fact that when there are more students in the class the teacher has fewer time with each individually. Students need time to ask their teachers questions and more importantly to have quality one on one time with them to cement their skills. Secondly, this is important because of how little money the Hartford public school system has to spend once it has reached it budget due to the per pupil expenditure rate which will be covered in the next section.

3. Per Pupil Expenditure:

Source: State Deptartment of Education 8

Source: State Deptartment of Education 8

Source: State Deptartment of Education 8

Since enrollment is in regards to the topic of finance it is also important that we take a look at the per pupil expenditure for the Hartford public school system. Since Hartford has about 11,000 more kids than the West Hartford district they should receive a substancial amount more money for those extra students. It is important to look at how the money given to the the schools are spent, especially in comparison to West Hartford. For the most part both districts are similar but total spending is in favor of Hartford. Hartford’s district is spending $3,000 more than West Hartford’s but is that really enough money to make up for those extra 11,000 children? When taking into account a child’s education and future it is not simply enough to split $3,000 11,000 ways. When you divide all that money up it comes out to roughly 27 cents per child. The lack of money that is donated to the Hartford public schools due to their economic status doesn’t satisfy the necessities that each child needs. Although they are given an amount which is supposed to meet the needs of the child, it really doesn’t. Higher enrollment with a smaller budget leads to the lack of school supplies, food, and teachers that we see within the Hartford public school system.

4. Staff:

Source: State Deptartment of Education 8

The staffs of Hartford public schools are paid just around the state average. This amount of money is paid out to them because it is not easy teaching in this district of public schools. Teachers here have one of the toughest jobs in Connecticut in teaching in Hartford. It is hard to find people who genuinely love teaching to the extent in which they do. Many students do not care about their performance and have fallen into a performance stereotype of “I cant get good grades so why try” and the teachers are the ones who must inspire them to change that. These numbers are similar to those of West Hartford and are one of the few closely comparable stats between them.

Source: State Deptartment of Education 8

Although the statistics for teachers were very similar to that of West Hartford it is important that staff experience and qualification are taken into account as well. Hartford’s percentage of teachers with their masters degree or higher is much lower than West Hartford’s as well as a good amount of the surrounding districts. This is a severe blow to the children’s ability to learn and prepare for the CMT. It is not about how much money the teachers make but more importantly whether or not they will be able to provide the students with the mental stimulation they need in order to continue to learn. Teachers with master’s degrees are able to provide that stimulation and push the children to learn which is necessary in order for them to do well on their testing.

District CMT Performance Since 1993:

A data table representation of CMT performance in Hartford since 1993. Data source: Connecticut Mastery Test 10 & Connecticut Student Assessment 11

Results:

Source: State Deptartment of Education 8

Source: State Deptartment of Education 8

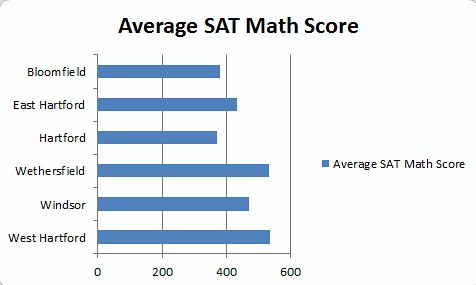

Now that we have looked both the averages in CMT scores for this year, as well as the positives and negatives in regards to the opportunities provided by the Hartford public school system, it is time that we look at Enrique’s results. He scored a 220 on the mathematical section, a 230 on the reading section, a 210 on the writing section, and a 220 on the science section. All of these numbers are similar to the district averages with a few points being higher or lower here and there. It is important to remember that Enrique just like so many of the other children in Hartford public schools sadly, was not put in a position to succeed from the get go. His scores are a reflection of how the racial inequality in the Hartford area stemming from the mid 1900’s has influenced the economic status as well as the educational success even for today’s youth.

Erik

Erik is the representation of a hypothetical boy from West Hartford, CT. Erik is in the 8th grade and from a very well off family in the West Hartford area. Him and his parents are born and raised in West Hartford and have been living in the same area all their collective lives. His father is a very successful lawyer and his mother is a stay at home mom. Erik attends public school in the West Hartford district and has just gotten his CMT scores back. Erik has been going to the best public schools in the area all of his life which have allowed him to train for the CMT through practice tests and adequate teaching over the past 8 years of him being in school. Before we take a look at the results of the CMT it is important that we look at the differences that Erik has had over the past years of learning in comparison to that of someone in the Hartford public school system. They are as follows:

1. Economic

West Hartford is listed as one of the top 50 wealthiest places in America. The average family income is $78,488, which is $11,000 more than the state average of 67,034. These economic benefits are crucial in funding the phenomenal public schools of the district. This economic superiority also allows for other benefits, which can yield to higher scores on the CMT such as tutors and practice tests.

Source: West Hartford CT Profile 5

2. Enrollment

Source: State Deptartment of Education 7

The enrollment of West Hartford public schools is at just about 10,000 kids, 11,000 less than that of Hartford public schools. This allows for smaller classes, which yields for more individual time and attention from the teacher on a daily basis. This alone time with teachers due to student teacher ratio allows students to learn in a one on one environment and gives them a safe environment to ask questions that they may not want to ask in front of their peers. They have more structured time to go over individual problems, which can lead to higher scores on their CMT testing.

3. Per Pupil Expenditure

Source: State Deptartment of Education 7

Source: State Deptartment of Education 7

West Hartford has very similar numbers to Hartford in regards to most categories. However, it is incredibly difficult for West Hartford to match the same per pupil expenditure due to the fact that they have 11,000 less children to take care of. The main difference in the two groups is in the the total expenditure category where Hartford is about $2,000 ahead of the state average and about $3,000 ahead of West Hartford. This shows a major lack in proper funding in the Hartford district. Hartford is given more money for the 11,000 more students they have, but even though they receive more money for those students is it really enough. $3,000 is not that substantial of a difference for 11,000 students especially when taking into account everything that those students need in order to get the most out of their schooling experience. Since they have fewer students enrolled and a much more manageable budget than surrounding districts they can afford better supplies and much more of them in comparison to other districts.

4. Staff

Source: State Deptartment of Education 7

Source: State Deptartment of Education 7

The staff of the West Hartford public schools is paid very similarly to that of the Hartford public school district. It is important to note that since the teachers are being paid so much they are expected to get the most out of their students, which they have shown the ability to do more than those from Hartford. The hefty amount of money that they are being paid reflects the strength of their teaching ability as well as their experience. This stat is the only closely comparable stat between West Hartford and Hartford.

Source: State Deptartment of Education 7

Source: State Deptartment of Education 7

It is not just important to note the amount of money the staff is being paid but also how qualified the teachers are. The amount of money they are being paid is due to the economic standing of West Hartford but is also due in part to the fact that they are the best and brightest out of most CT teachers. The fact that just about everyone in the West Hartford schooling district says so much about the quality of his or her teachers. In comparison with Hartford there is almost a 25% difference in teachers who have already obtained their masters. Teachers in West Hartford have had more time learning how to teach and therefore have a better chance in provoking more thought and stimulating student’s minds, better preparing them for the CMT.

West Hartford CMT Results Since 1993:

A data table representation of CMT performance in Hartford since 1993. Data source: Connecticut Mastery Test 10 & Connecticut Student Assessment 11

A data table representation of CMT performance in Hartford since 1993. Data source: Connecticut Mastery Test 10 & Connecticut Student Assessment 11

Results:

Source: State Deptartment of Education 7

Now that we have looked at a few of the main points which makes the West Hartford public school system so different, it is time for the results of Erik’s CMT. His results are very similar to those of many West Hartford’s public school students. Erik scored a 275 on math, a 260.3 on reading, a 270 on writing, and a 267 on science. His scores are very close to the averages listed above which is a greater example of just how well the West Hartford public school system prepare their children for the tests. Erik was blessed to be live on the more prominent side of Prospect Ave. West Hartford is much more financially well off and therefore students like Erik have a higher opportunity. It is apparent that even in today’s society there are still benefits stemming from the suburbs of the early 1900’s.

Closing

The results between both of the public school systems are astounding. It is apparent that over time race has attributed to economic status. It is also apparent that economic status provides a much more efficient and superior environment for education. More money means better supplies, better teachers, and more opportunities. Overall the West Hartford school system has demonstrated that it prepares its children for the CMT and also for all forms of education better than the Hartford public school system. As stated earlier, West Hartford was one of the earliest suburbs in CT and therefore has always had more opportunity as well as more money to fund education. The next step in this process is figuring out the first leap that needs to be made in order to catch the Hartford public school system up in hopes to get their achievement scores a little bit closer to those on the other side of Prospect Ave.

About the Author:

Bobby Moore is a junior at Trinity College in Hartford, Ct. He is from Silver Spring Maryland. Before Trinity went to the Landon School in Bethesda, Maryland. Bobby is an Educational Studies major with his concentration being in gender and racial studies.

Footnotes

1. Connecticut CMT. “Interactive Web Sample Items.” Interactive Web Sample Items. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Dec. 2011. <cuacs8.mck.ncsu.edu/mathsampleitems/main.html>.

2. Department of Education. “The Center for Comprehensive School Reform and Improvement – State Achievement Data Web Sites.” The Center for Comprehensive School Reform and Improvement – Home. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Dec. 2011. <http://www.centerforcsri.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=341&Itemid=23>.

3. Dougherty, Jack . “Maps created with UConn MAGIC | On The Line.” On The Line | a public history web-book by Jack Dougherty & colleagues Fall 2011 preview edition. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Dec. 2011. <http://ontheline.trincoll.edu/maps/>.

4.Google. “Google Maps.” Google Maps. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Dec. 2011. <http://maps.google.com/>.

5. “West Hartford, Connecticut (CT) profile: population, maps, real estate, averages, homes, statistics, relocation, travel, jobs, hospitals, schools, crime, moving, houses, news, sex offenders.” Stats about all US cities – real estate, relocation info, house prices, home value estimator, recent sales, cost of living, crime, race, income, photos, education, maps, weather, houses, schools, neighborhoods, and more. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Dec. 2011. <http://www.city-data.com/city/Hartford-Connecticut.html>.

6. “Hartford, Connecticut (CT) profile: population, maps, real estate, averages, homes, statistics, relocation, travel, jobs, hospitals, schools, crime, moving, houses, news, sex offenders.” Stats about all US cities – real estate, relocation info, house prices, home value estimator, recent sales, cost of living, crime, race, income, photos, education, maps, weather, houses, schools, neighborhoods, and more. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Dec. 2011. <http://www.city-data.com/city/Hartford-Connecticut.html>.

7. State Department of Education. “State Department of Education – CEDaR.”SDE Portal West Hartford. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Dec. 2011. <http://sdeportal.ct.gov/Cedar/WEB/ct_report/SnapshotGeneral.aspx>.

8. State Deptartment of Education. “State Department of Education – CEDaR.” SDE Portal Hartford. N.p., n.d. Web. 11 Dec. 2011. <http://sdeportal.ct.gov/Cedar/WEB/ct_report/SnapshotGeneral.aspx>.

9. Douglas Massey, American apartheid : segregation and the making of the underclass (Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1993).

10. “Connecticut Mastery Test – Connecticut State Department of Education.”. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Dec. 2011. <http://www.csde.state.ct.us/public/cedar/assessment/cmt/cmt_data.htm>.

11. eMetric. “Connecticut Student Assessment.”. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Dec. 2011. <http://www.ctreports.com/>.