Looking at the past for keys to the future

By Eric C. Stoykovich

College Archivist and Manuscript Librarian, Watkinson Library

Photos courtesy of Trinity Archives

Two world wars. The Great Depression. Global pandemics. Trinity College, throughout its nearly 200-year history, has persisted through these trying times and more.

The situation sparked by COVID-19 presents its own challenges, with Trinity finding ways to adapt. Students, faculty, and staff learned midsemester how to study, teach, and keep the college running, all from remote locations. Major campus celebrations, including Commencement and Reunion, had to be postponed. Even this story was written from home, using digitized historical materials mainly from the College Archives in the Watkinson Library.

While the experiences of the past may not provide direct lessons for how Trinity might endure the current pandemic, they do showcase how the college has persisted despite existential threats.

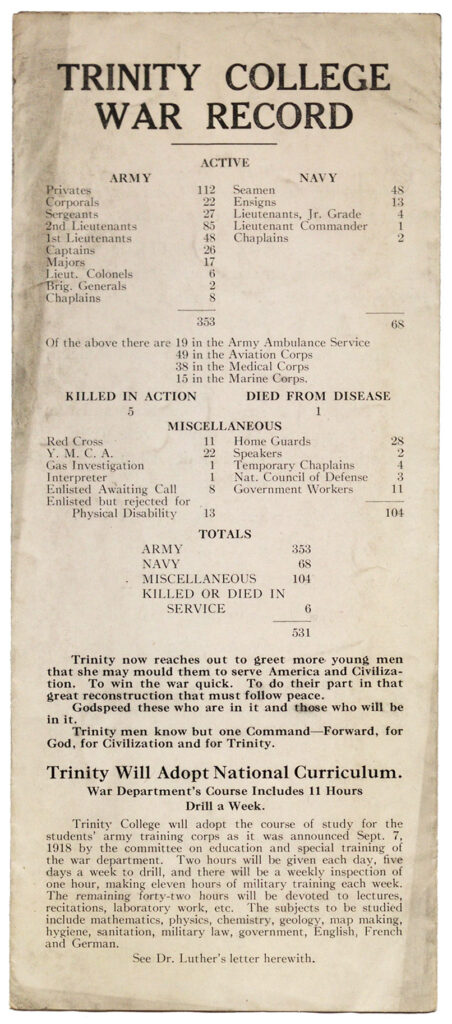

MOBILIZING FOR WAR

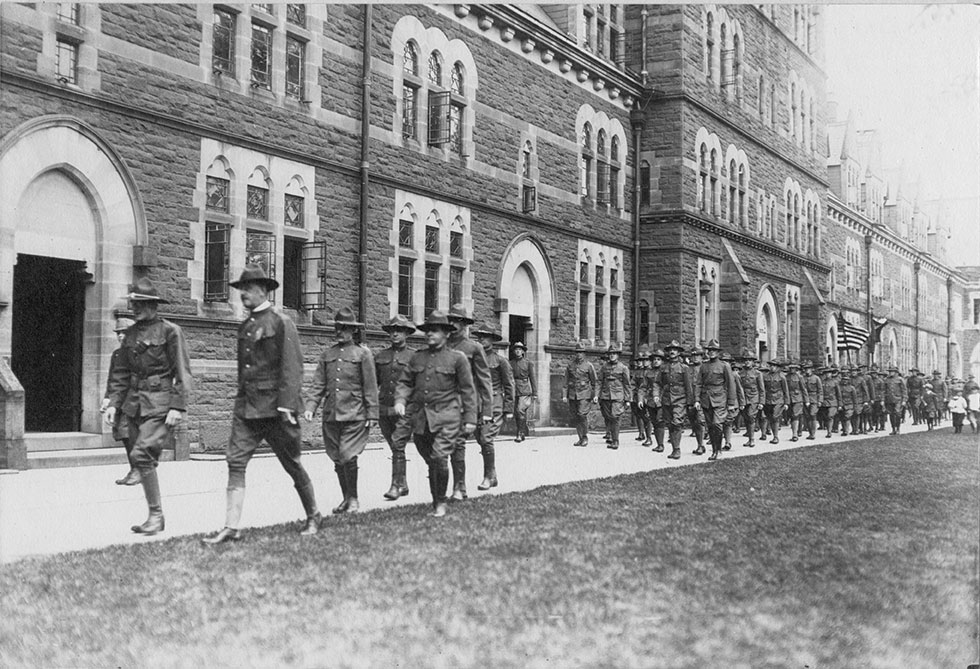

More than 480 Trinity students and alumni would eventually serve in the military in World War I, but many Trinity leaders responded to the declaration of war by the U.S. Congress in April 1917 with trepidation. A war could be damaging to the college’s future because it would draw students away from their usual studies. By then, half the students had begun receiving military officer training from the Connecticut National Guard. Though opposed by some of the faculty, a credit course on military science became compulsory in September. Throughout that fall, the war dominated talk along the Long Walk.

More than 480 Trinity students and alumni would eventually serve in the military in World War I, but many Trinity leaders responded to the declaration of war by the U.S. Congress in April 1917 with trepidation. A war could be damaging to the college’s future because it would draw students away from their usual studies. By then, half the students had begun receiving military officer training from the Connecticut National Guard. Though opposed by some of the faculty, a credit course on military science became compulsory in September. Throughout that fall, the war dominated talk along the Long Walk.

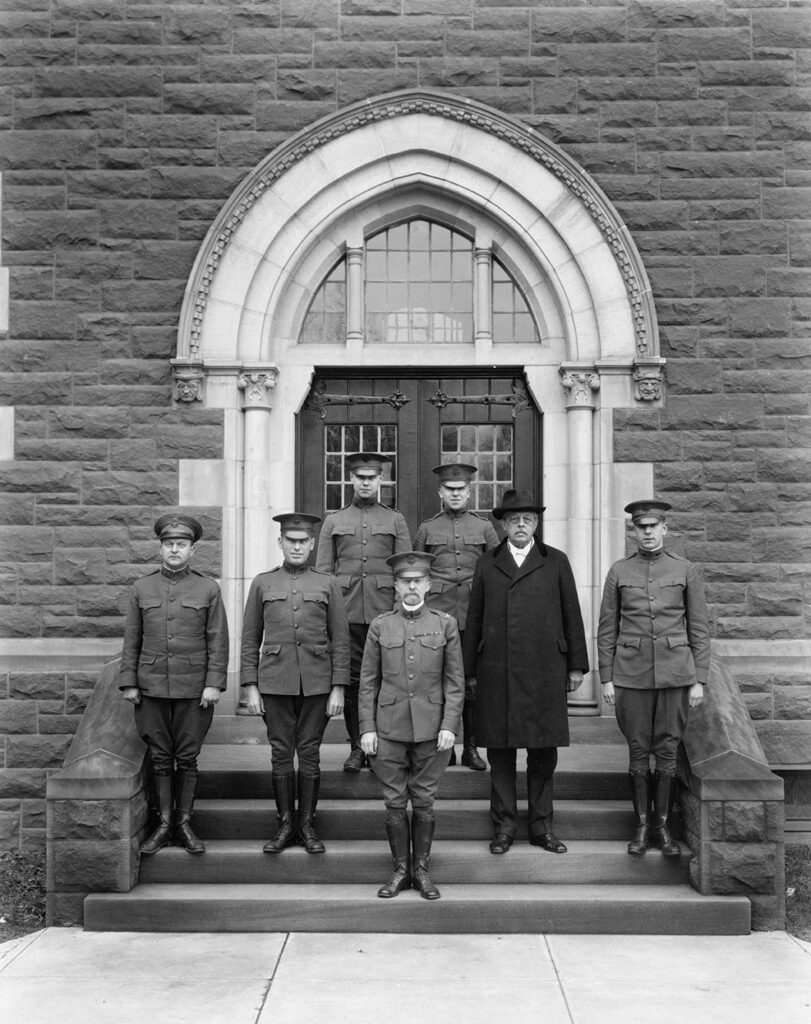

As Trinity President Flavel S. Luther reported to the Board of Trustees one year into the war, the number of students enrolled on campus had dropped about 40 percent, as many enlisted in the U.S. Army or Navy. The effect on student life was sociological, Luther thought, felt in both a decline in the quality of “scholastic work” and in the number of student leaders on campus. He also saw it as psychological: “Like their elders[,] the students have been disturbed, anxious, and unable to concentrate on their regular work,” he said. Even some professors were granted leaves of absence to assist in war work. The matter of whether to award students who left Trinity early with a regular diploma or a “war certificate” seemed minor when so many might not return. When a Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) was established under the direction of Calvin Cowles, a retired Army colonel, 94 students eagerly entered.

By October 1918, the effect of war on the college was unmistakable, particularly as Luther enrolled the college in a U.S. War Department training program. Students between 18 and 21 who remained on campus, or about 172 men, formed a Student Army Training Corps (S.A.T.C.). They were paid $30 a month.

Other changes also were evident. To feed and house the soldiers in training, the dining room was retrofitted as a mess hall, and a modern kitchen was set up. “War gardens” appeared east of the gymnasium. By November, electric lights and shower baths had been installed, the latter mandated by “Government inspectors.” Whether to discipline uniformed men who failed to attend Chapel went unresolved, as the “Government will not compel its soldiers to attend Prayers.” After the trustees decided in late October to suspend compulsory Chapel, Luther urged students to attend regardless, not just for their own good, “but for the good of the College.”

Luther predicted that universal military training would become a part of every college in America. Yet, only a handful would make good officers, as just 18 were sent from Trinity’s S.A.T.C. to complete army officers’ training. Nevertheless, Luther’s claim that the college had been “completely revolutionized” by the war was not far off the mark. At Trinity’s 1923 centennial celebration, the memorial service for the college’s war dead included a list of 21 who had died in connection with the war.

A DIFFERENT GLOBAL PANDEMIC

At the peak of this militarization of Trinity, a second wave of the so-called “Spanish flu,” a strain of influenza, arrived in Connecticut on September 1, 1918. Then thought to be caused by bacteria and known as originating from Spain, the malady first appeared in New London at the naval hospital and spread within a week through the civilian population in southeastern Connecticut because many seamen were housed in private homes.

At Trinity, the fall semester had opened unusually. In late September, the army conducted physical examinations, and all “Trinity students physically fit for full military service were inducted” into the S.A.T.C. on October 1. The army’s emphasis on a regimen of physical health and fitness meant that military leaders in conjunction with Luther—not the board—would take the lead in any response to the influenza then circulating in Hartford. In fact, in July, the trustees already had voted to empower Luther “to execute any and all other papers required by the National Government in connection with Military Training.”

Virology was in its infancy, and antibiotics to fight secondary infections were nonexistent. Still, The Hartford Courant offered steps to avoid catching the disease, which often progressed to pneumonia: avoid “indoor public gatherings, [d]o not allow others to talk or breathe into your face,” and if stricken with fever and chills, leave work and stay at home “for a few days.” While state medical and prison facilities imposed quarantines “against visitors … until further notice,” Hartford was one of Connecticut’s cities that kept its schools and theaters open, though monitored by the State Department of Health.

In early October, the students of the S.A.T.C.—the majority of students at Trinity—were quarantined to campus by “official order” to prevent them from “contracting influenza.” On October 27, a Chapel service commemorated 14 Trinity men who were known to have died in war service. Among these were several who died of influenza outside of Connecticut while working in various capacities for the Red Cross or the army.

Two days later, Major Dwight Tracy, the newly appointed surgeon for the S.A.T.C., augmented the medical capacity on campus by overseeing the inoculation and vaccination of the students in the infirmary in Seabury Hall, where they were to remain for 24 hours. It is unknown which vaccines—including several thought to target influenza, along with others for typhoid and venereal disease—the army administered to the soldier-students.

By November 1, cases of influenza in Hartford had topped 9,000, with 600 reported dead, though some believed the worst was over. Without apparent explanation, the Trinity campus quarantine also ended permanently that day. S.A.T.C. men could receive passes to leave campus but were told not to ride on trolleys or drink at soda fountains. Instead, one troop marched in formation to Goodwin Park in downtown Hartford. The compliance of students with army orders seems to have been high.

However, the “serious effects of the influenza epidemic” had begun to affect Trinity students and alumni, both on and off campus. A newspaper report of November 29 blamed “a military skirmish following a hard rain” as the “cause” of several “hard colds” among the S.A.T.C. men. Twelve days later, the armistice ended World War I, and the discharge from the army of all S.A.T.C. students, except for two suffering from the flu, took place a month afterward.

As many as 10,000 people across Connecticut may have died as the epidemic raged from September 1918 through February 1919. The crisis had exacted a toll on the Trinity community, too, even if wartime heroism or national unity was what people wanted to remember through various commemoration ceremonies. The deaths of at least 12 of the 21 Trinity men listed on the war memorial tablets erected in 1938 in the Chapel—more than 50 percent—were actually attributable to influenza or pneumonia unconnected to battlefield injuries.

THE PRICE OF HISTORY

The toll of war and epidemic disease on Trinity were lasting. Luther, after serving as president for 15 years, resigned effective July 1919. For the next two to three years, the college suffered with lower enrollments, although the immediate interest in history courses exceeded available faculty. Students returning from life in army camp or battle were less prepared for academic study. High school seniors whose education had been interrupted by influenza or wartime activities had fallen behind. Between 10 and 20 percent of the students matriculating in 1920 and 1921 dropped out after one year. It was not until the graduation of the Class of 1922 that the remaining S.A.T.C. students departed. By then, it was obvious that Trinity College, once again, would endure.

Eric C. Stoykovich, Trinity’s college archivist and manuscript librarian, joined the Watkinson Library staff in 2019 after working for the University of Maryland’s Special Collections for three years. Prior to that, he worked on digitization at the Library of Congress and for Fold3/Ancestry.com. Stoykovich earned a B.A. in history from Brown University, a Ph.D. in history from the University of Virginia, and an M.L.S. from the University of Maryland. His Trinity ties run deep: he is the son of Petar V. Stoykovich, Trinity Class of 1966, and great-grandson of Victor E. Rehr, Trinity Class of 1906. Trinity alumni and others seeking historical information about the college are welcome to contact him at eric.stoykovich@trincoll.edu.