Archive for May, 2012

[Posted by Richard Mammana, graduate student at Yale University]

In connection with an ongoing project on Anglican liturgical translations, I visited the Watkinson Library in February to consult a Japanese-language book I found through a Worldcat search.

In connection with an ongoing project on Anglican liturgical translations, I visited the Watkinson Library in February to consult a Japanese-language book I found through a Worldcat search.

This important title is an early translation—perhaps the earliest now extant—of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer into Japanese, entitled 聖公會祷文 Seikōkai tōbun or Prayer Book for the Holy Catholic Church. (The nineteenth-century missionary organizers of Anglican/Episcopal churches in China, Japan and Korea identified their denomination as the “Holy Catholic Church” in distinction from the Roman Catholic Church or any name—such as “Anglican”—that would imply a connection to England.)

Anglican evangelistic activity in the Japanese archipelago began in 1846 with the arrival of Hungarian Jewish convert and medical missionary Bernard Jean Bettelheim in what is now the Japanese prefecture of Okinawa. The second, and major, wave of missionary activity began with the settlement of the American Episcopalian Channing Moore Williams (1829-1910) in 1859 and Anglo-Canadian Alexander Croft Shaw (1846-1902) in 1873. American, English, and Canadian missionaries subsequently co-operated locally in educational, printing, medical and other projects. The title page of Seikōkai tōbun identifies it as 英美宣教著版, or the responsibility of “Anglo-American missionaries.”

The 44 leaves of the book contain, in order: a table of holy days (Easter, Ascension Day, Sundays after Trinity, etc.) for 1880-1892, followed by a table of contents, Morning Prayer, Evening Prayer, and the Litany, all translated from the English 1662 Book of Common Prayer. The table of contents identifies another range of absent material not included in this volume: translations of the services for Holy Communion, the baptism of infants, private baptism, the baptism of adults, the catechism, and the rite for confirmation by a bishop. The title page does not indicate a place of publication.

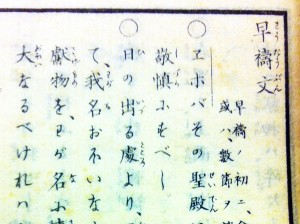

The text is presented in traditional Japanese book format, namely, text in vertical downward columns following from right to left on the page. To the right of each Chinese character (kanji) in the text, the translators have provided the Japanese syllabic equivalent in furigana as a reading aid. This was likely useful primarily for missionaries, but could also have been helpful for native speakers of Japanese with lower levels of reading ability.

The titles for Morning Prayer (早禱文), Evening Prayer (晩禱文), Holy Communion (聖餐式), and the Catechism (公會問答) are remarkable for their stability from this translation through the 1959 translation of the Book of Common Prayer into Japanese. It is notable that the name for the Litany in this translation is the English-derived Ritanii (リタニー), rather than the later Japanese-language version 嘆願 or Tangan.

One notable aspect of the text of this translation is that it uses the characters ヱホバ (Ehoba) as a Japanese-language equivalent for Jehovah in liturgical material derived from the Old Testament [see first pic, above]. This decision would prove controversial later, for example in the anonymous 1890 pamphlet On the Use of the Word Ehoba in the Prayer Book of the Nippon Sei Kokwai (Tokyo: Hakubunsha).

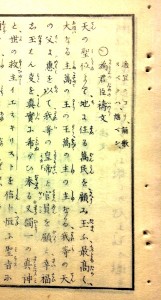

Another notable feature of this translation is its inclusion of set liturgical prayers for the Imperial House of Japan. Most contemporary Anglican liturgical translations were made for use in missionary contexts where the Church of England worked alongside British colonial authorities; prayers for civil authorities in these translations—including Cree, Zulu, Mohawk, Melanesian languages, Swahili, etc.—all name the current British monarch, Queen Victoria, in their set intercessions. Instead, this translation was produced for use in a country never colonized by Americans or the British; accordingly, prayers are appointed for the imperial family, which at this time consisted of the Emperor Meiji (1852-1912), Empress Shōken (1849-1914), their children and extended relations.

Another notable feature of this translation is its inclusion of set liturgical prayers for the Imperial House of Japan. Most contemporary Anglican liturgical translations were made for use in missionary contexts where the Church of England worked alongside British colonial authorities; prayers for civil authorities in these translations—including Cree, Zulu, Mohawk, Melanesian languages, Swahili, etc.—all name the current British monarch, Queen Victoria, in their set intercessions. Instead, this translation was produced for use in a country never colonized by Americans or the British; accordingly, prayers are appointed for the imperial family, which at this time consisted of the Emperor Meiji (1852-1912), Empress Shōken (1849-1914), their children and extended relations.

This translation is not identified in either of the major Anglican liturgical bibliographies: it is not included in William Muss-Arnolt’s Book of Common Prayer among the Nations of the World (1914) or David Griffiths’ Bibliography of the Book of Common Prayer 1549-1999 (London: The British Library; New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press, 2002). Griffiths does list a contemporary title as 67:1 (p. 515): “(Seikokai tobun . . . ) [offices of worship for the Seikokai] 4º; japanese characters; compiled by a conference of missionaries from SPG, CMS & PECUSA; Part I (morning & evening prayer, litany, collects & old testament lections) was completed at Tokyo in 1879 & Part II (occasional offices) at Osaka in 1882.”

This is not, however, the item in the Watkinson Library’s collection. The title page of the Watkinson’s copy of Seikōkai tōbun says that it was published in the twelfth year of the reign of Emperor Meiji, or 1879; yet its contents do not correspond to the listing in the Griffiths bibliography. It is also not included in the exhaustive Meiji Digital Library of the National Diet Library in Tokyo.

In light of the absence of this title from any Japanese union catalogues and its omission from standard, comprehensive liturgical bibliographies, it seems possible to me that this is a unique extant copy of this title. This is even more likely in view of the fragility of the paper on which this item was produced, and the extensive World War Two carpet-bombing of several Japanese cities with major library collections.

The decision of the Watkinson Library to digitize this item will make a major early Japanese-language missionary publication available to a wide audience. It will also help to expand, correct, and clarify existing Anglican liturgical bibliography, and to supplement scholarly understanding of the ways in which Japanese-speaking Christians worshiped during a period of extraordinary cultural change and exchange.

Pic 1, above: A text from Morning Prayer using Ehoba as the Japanese equivalent of Jehovah

Pic 2, above: The beginning of the “State Prayers” for the Imperial Family