[Posted by Wendi Delaney, for prof. Chris Hager’s course, ENGL 329: Civil War Literature]

Confederate Receipt Book. A compilation of over one hundred receipts adapted to the times. Richmond, Virginia: West & Johnston, 1863.

Confederate Receipt Book. A compilation of over one hundred receipts adapted to the times. Richmond, Virginia: West & Johnston, 1863.

In 1863 on a cool day in early fall a young Confederate woman is preparing to receive visitors for the afternoon. Because of the Union blockade she is not able to present herself in the latest fashions, nor is she able to offer them the usual refreshments of coffee or tea, but she is learning to make do with what she is able to find. She has not bought a new dress for over two years and today is wearing an older day dress that she has attempted to make look new by repurposing some bits of lace from an old worn out dress that is no longer serviceable. She is wondering what she can serve for refreshments because the coffee which she normally serves is either no longer available, or when it is the price is so high she cannot afford to buy it. As she looks through her newly acquired Confederate Receipt Book for ideas of what to serve her guests she comes across a recipe for coffee made with acorns. Because it is autumn she has good supply of fresh acorns underneath the oak tree behind her house. With high hopes that this substitute for coffee will be better than the last, she goes outside to collect the acorns.

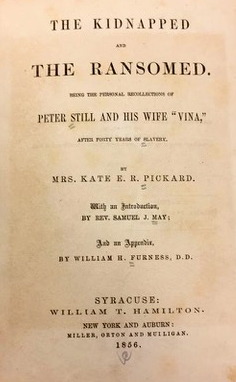

In Trinity College’s Watkinson Library there is a small, 154-year-old, 28-page cookbook with dry, brittle, yellowed pages and a front cover no longer attached. It was published in 1863 by West and Johnson in Richmond, Virginia and is titled, Confederate Receipt Book. A compilation of over one hundred receipts, adapted to the times.[1] Cookbooks are not a unique item to kitchens in America, nor is it unique for them to be adapted to meet the needs of regional people with ingredients only found in specific areas. What makes this item unique is that it was published for the people of the new Confederate nation and was tailored to their unique situation of not having items available to them because of the Union blockades. It is believed to be the only cookbook published in the South during the Civil War.[2] Cookbooks form a literary genre that fulfills the need of educating people on how to make culinary dishes. Some also contain other information and helpful hints to make a household economical and efficient. When they are tailored to a specific geographic region, event, or time period, they tell of the ingenuity and creativity of people adapting to changes or challenges found in their daily lives. They also show a willingness of people to share their knowledge and experience to help others. The contents of this small book reveal some of the challenges Confederate women faced during the Civil War and how Confederate women of all classes—wealthy, yeoman, and poor—were expected to deal with them.

After the Civil War broke out, the Union blockade took hold of southern ports, effectively preventing the South from shipping out or receiving any supplies or commodities. Because of this the cost for food, household items, and clothing began to rise. To adjust to the changing conditions women started to make sacrifices by going without some of the luxuries they were used to. During the summer of 1861 one woman from Virginia felt “intensely patriotic and self-sacrificing” when she resolved to give up ice cream and cakes.[3] Because women were not allowed to physically fight in the war, making these sacrifices helped them feel like they were doing their patriotic duty for the cause; they believed the food and materials they were not using for themselves were being used for their men in the Confederate army. This belief is reflected in a book published in 1864 by Alex St. Clair Abrams called The Trials of a Soldier’s Wife, in which the heroine explains, “Woman can only show her devotion by suffering, and though I cannot struggle with you on the battle-field, in suffering as I have done, I feel it has been our holy cause.”[4] As the war continued, the effects of the blockade became more intense forcing women to sacrifice more than just ice cream and cake. The average cost of feeding a family for a month rose from $6.55 in 1860 to $68.25 in 1863.[5] Items that were either in short supply or very high-priced included coffee, tea, sugar, meats, flour, medicines, household items such as soap and candles, and clothing and cloth material. Many women recorded the shortages, costs of goods, and how they dealt with the challenges in their diaries.

After the Civil War broke out, the Union blockade took hold of southern ports, effectively preventing the South from shipping out or receiving any supplies or commodities. Because of this the cost for food, household items, and clothing began to rise. To adjust to the changing conditions women started to make sacrifices by going without some of the luxuries they were used to. During the summer of 1861 one woman from Virginia felt “intensely patriotic and self-sacrificing” when she resolved to give up ice cream and cakes.[3] Because women were not allowed to physically fight in the war, making these sacrifices helped them feel like they were doing their patriotic duty for the cause; they believed the food and materials they were not using for themselves were being used for their men in the Confederate army. This belief is reflected in a book published in 1864 by Alex St. Clair Abrams called The Trials of a Soldier’s Wife, in which the heroine explains, “Woman can only show her devotion by suffering, and though I cannot struggle with you on the battle-field, in suffering as I have done, I feel it has been our holy cause.”[4] As the war continued, the effects of the blockade became more intense forcing women to sacrifice more than just ice cream and cake. The average cost of feeding a family for a month rose from $6.55 in 1860 to $68.25 in 1863.[5] Items that were either in short supply or very high-priced included coffee, tea, sugar, meats, flour, medicines, household items such as soap and candles, and clothing and cloth material. Many women recorded the shortages, costs of goods, and how they dealt with the challenges in their diaries.

Among the many items written about in Civil War diaries, coffee gets a lot of attention. During the war the price of coffee rose from 30 cents per pound up to $50 per pound.[6] In some parts of the South the price soared as high as $70 per pound.[7] Because of the scarcity and soaring cost of coffee, many tried to find alternative ingredients that would be an acceptable alternative, but it was not an easy task. Parthenia Antoinette Hague lamented the poor substitutes and popularity of the drink when she wrote, “One of our most difficult tasks is to find a good substitute for coffee. This palatable drink, if not a real necessary of life is almost indispensable to the enjoyment of a good meal, and some Southerners took it three times a day.”[8] Items used to replace the coffee bean included rye, wheat, sweet potatoes, chestnuts, chicory, and other grains and seeds that could be roasted and ground.[9] In The Confederate Cookbook under the section for “MISCELLANEOUS RECEIPTS” there is a receipt that calls for acorns to be prepared in place of the treasured coffee bean. Most of these substitutions were so intolerable some chose to go without as in the case of one prominent housewife of Virginia who stated “We must do without it except when needed for the sick. If we can’t make some of the various proposed substitutes appetizing, why we can use water. That, at least, is abundant, and can be given without money and without price.”[10]

Wheat flour was another food item that was in short supply. Many of the larger plantations were focused on planting more cash crops such as cotton or rice, while some of smaller farms and plantations would cultivate some cotton or rice but would plant more food crops such as wheat.[11] Wheat that was grown in the southern states before the war would have been sold north for processing and in return the flour would be sold to the southern states. Once the blockade was in place that process stopped. As with coffee, southern women had to find an alternative for wheat flour, and one alternative was rice flour. In the Appendix of the Confederate Receipt Book, there are 2 ½ pages dedicated to “Recipes for Making Bread, &c., From Rice Flour.” This section of recipes was sent in to the Editors of the Columbus Sun, in Russel County, Alabama, by Elizabeth B. Lewis, who felt the need to share her knowledge with other women who were asking how to make bread with rice flour.[12] This section includes recipes for bread, Johnny cakes, sponge cake, rice pudding and rice griddle cakes.

As many women do today women of the Civil War tried to stay up on the latest fashions. Southern women found it difficult to do this because the Union blockade prevented shipments of new clothes and materials used to make new clothes. Some women became embarrassed when they wore out their silk dresses and had to wear dresses made from calico, which was a material worn by slaves and servants. Just as Scarlett O’Hara, in the movie “Gone with the Wind,” made a new dress from green curtains, many women made new clothing from materials found around their house, like bed-ticking or the lining of a pre-war garment. They would also re-adorn dresses using old lace or materials from other worn-out dresses[13] Women reading the Confederate Receipt Book found a section called “HINTS FOR THE LADIES” dedicated to helpful tips on how to “freshen up a dress of which they have got tired, or which may be beginning to lose its beauty.”[14]

The longer the war continued the more dire Confederate women’s situations became. In 1864 one Confederate official informed President Davis that people were starving to death.[15] Southern women were no longer feeling it was their proud patriotic duty to make the sacrifices they were so willing to make at the onset of the war. They became desperate and in March of 1863, the year this book was published, “Bread Riots” occurred in Richmond and many others towns across the South. In Richmond women marched on Capitol Square armed with knives, pistols, and hatchets demanding that shop owners lower their prices. When no acceptable solution was reached they raided local shops, taking items such as food, shoes, clothes, brooms and hats.[16] The timing of publication for this book may have been a coincidence, but it may have been published as a response to the riots as a way to help the women of the South find alternatives and ease some of the hardships they were enduring.

[1] Receipts is another word for recipes.

[2]Dorothy Denneen Volo and James M. Volo. Daily Life in Civil War America (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1998), 232.

[3] Faust, Drew Gilpin. Southern Stories. Slaveholder in Peace and War. (Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press, 1992), 125.

[4] Faust, 119.

[5] Volo pg 57.

[6] Brock, Sallie A. Richmond during the War: Four Years of Personal Observation, by a Richmond Lady. (New York: G.W. Carleton & Co., 1867), 79, https://archive.org/stream/richmondduringwa01broc#page/n0/mode/1up.

[7] Hague, Parthenia Antoinette. A Blockaded Family. Life in Southern Alabama during the Civil War. (1888. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 1991), 101. In her book Hague gives an idea of how much work an average man would have to do in order to afford just a pound of coffee when she writes, “A good workman received 30 dollars per day so it would take two days of hard labor to buy one pound of coffee.”

[8] Hauge, 101.

[9] Brock, 79.

[10] Brock, 79.

[11] Hague, xviii.

[12] Confederate Receipt Book, 25.

[13] Thompson, 38.

[14] Confederate Receipt Book, 27.

[15] Faust, 125.

[16] Volo, 58.