[Posted by Erika Jenns, Indiana University ’13]

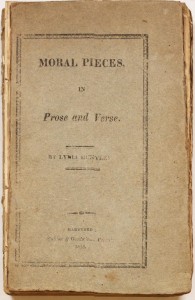

As I near the end of my journey through Lydia Sigourney’s life and published works, I’ve begun to examine the Watkinson’s holdings that pertain to her family as a whole. The Sigourney family maintained an interesting and eclectic collection of literary pieces. I’ve come across books inscribed by Lydia’s daughter, Mary, and her son, Andrew, books that Lydia owned or that were given to her by friends, and items that belonged to her husband, Charles.

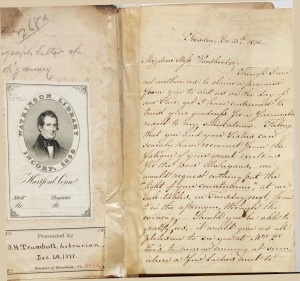

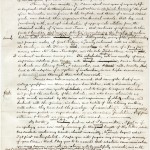

One particularly interesting item is a letter (fragment) written by Charles Sigourney to Thomas Jefferson, and Jefferson’s subsequent reply. Aside from the allure of handling a letter written by Thomas Jefferson, I was awestruck upon first seeing the careful, elegant handwriting–which appears as if it has been typed. Each line is neat and straight; few words are crossed out. In their correspondence, the men share their opinions and suggestions regarding the reform of collegiate education in America and what should be done to improve it. NOTE: I have largely kept the spelling, and made a few editorial changes (especially punctuation), but include the scans so that readers may see the originals.

Letter fragment from Charles Sigourney to Thomas Jefferson (the first page is not present in the collection):

Letter fragment from Charles Sigourney to Thomas Jefferson (the first page is not present in the collection):

…. these objections, which may at least be guarded against input, if not remedied, your plan may be successful, and certainly, for one, I hope you may find it productive of all the good you have ever anticipated from it.

I have long been sensible, for I have spent some years of my early life in England, that in thoroughness of instruction in classical learning the first of our Universities are inferiour to the English, and those of a second & third grade even behind their superiour Academical schools. That deep-read familiarity with, and past introduction of appropriate citation from, the classical writers of Greece and Rome, that readiness of reference to their facts & beauties, that “curiosa felicitas,” in combining the beauties of modern diction with classic corruption of Cicero & Plato, resulting from an understanding stored with the wisdom of antiquity, which distinguishes many of the parliamentary and forensic crates of Great Britain, is so rarely witnessed with us either in the Senate, or in the Forum, that, except in the case of a very few, among whom W. John Randolph, and the late Fisher Ames may be remembered it is almost unknown among us. The introduction therefore, into our country of some superior scholars from Europe will certainly have a tendency to elevate our literary taste, ambition & character, and will, besides, I trust, lead to the adoption of a system of instruction, in our higher seminaries of learning, more thorough than what now exists.

I would here take occasion to remark that some of the best of our College – professors are those who have been taken, with a discriminating hand, from our own youth, sent to Europe to expand their views and perfect the maturity of their talents, and who have returned to us with minds enriched by the views and experience of older nations, and imbued with the opinions, wisdom, and habits of the literary worthies, with whom they have had the privelege of associating. Thus imposing an European polish or superstructure on an American foundation. Professors Silliman & Everett are examples of this remark.

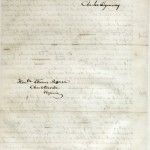

My dear Ser when I look back on what I have written, I feel as if an apology were now really necessary for the unusual length of this letter, which has swelled under my hand, almost insensibly, to very much beyond what I at first contemplated. I hope you will forgive my occupying so much of your time. And I beg you to be assured that whatever communication you may honour me with in return will be gratefully received, and in the spirit of perfect friendliness & candour, (and I add, because I know that evil has arisen from the license taken in similar cases) the, unsolicited, pledge on my part that it shall not, or any part of it, be suffered to make it’s appearance in the newspapers. With great respect I have the honour [sic] to be / Your very obedient servant / Charles Sigourney / Hon.ble Thomas Jefferson / Charlottesville / Virginia

My dear Ser when I look back on what I have written, I feel as if an apology were now really necessary for the unusual length of this letter, which has swelled under my hand, almost insensibly, to very much beyond what I at first contemplated. I hope you will forgive my occupying so much of your time. And I beg you to be assured that whatever communication you may honour me with in return will be gratefully received, and in the spirit of perfect friendliness & candour, (and I add, because I know that evil has arisen from the license taken in similar cases) the, unsolicited, pledge on my part that it shall not, or any part of it, be suffered to make it’s appearance in the newspapers. With great respect I have the honour [sic] to be / Your very obedient servant / Charles Sigourney / Hon.ble Thomas Jefferson / Charlottesville / Virginia

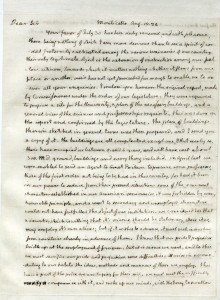

Thomas Jefferson’s Response to Charles Sigourney:

Dear Sir / Monticello Aug. 15. 24.

Dear Sir / Monticello Aug. 15. 24.

Your favor of July 30 has been duly recieved, and with pleasure, there being nothing of which I am more desirous than to see a spirit of cordial fraternity cultivated among the various seminaries of our country. Their only legitimate object is the extension of instruction among our fellow-citizens, towards which it matters nothing whether it flows from one place or another. Our’s has not yet proceeded far enough to enable me to answer all you enquiries. I inclose you however the original report, made by Commissioners under the order of our legislature. They were required to propose a site for the University, a plan of the necessary buildings, and a general view of the sciences and professorships requisite. This was done in the report and confirmed by the legislature. The plan of buildings therein sketched in general terms was then prepared, and I send you a copy of it. The buildings are all compleated except one, & that nearly so. These have occupied us between 5. and 6. Years, and will have cost about 300. M. D. ground, buildings and every thing included. In April last we were enabled to send an agent to Great Britain to procure some professors, those of the first order not being to be had in this country, for had it been in our power to seduce from their present situations some of the eminent characters established in our American seminaries, it was forbidden by every honorable principle; and a resort to secondary and unemployed characters would not have fulfilled the object of our institution. We considered too that a country which is willing that it’s science should be stationary, there it is, may employ it’s own eleves [pupils (French)]; but if it wishes to advance, it must seek instruction from countries already in advance of them. I know that our pride & prejudices bristle up at the employment of foreigners, but it is science we want, and to this we must sacrifice our pride and prejudices. Some difficulties will arise in accommodating to our habits the ideas, methods and manners of those we employ. This too is a part of the price we are to pay for their aid. We must meet the difficulty, compromise with it, and make up our minds, with the honey, to swallow the few dregs we cannot separate from it. No good in life can be obtained pure and unmixed. We must take it as it is offered, alloyed always with some evil. And at what other price have we obtained all our arts and sciences? Our constitution I think is good. We are, as we ought to be, made regularly and highly responsible to the legislature for our administration. Moral and pecuniary regulations for the government and discipline of our university, I am not able to give you, because we have not yet acted on them. We defer that until autumn when we hope to derive some aid from the experience of our professors. A paragraph cut from a newspaper, and now inclosed, will give you, as far as is yet ascertained, a view of our general schools, the time fixed for their opening, the probable expences, and some other particularities.

The university is but one part of a general plan which I proposed to our legislature five and forty years ago. I need not detail to you the historical circumstances which, till lately, have prevented our entering on it. That proposed the establishment of primary schools in words to be laid off about 5. or 6. miles square, intermediate colleges in large districts, distributed over the state, for the languages, and other instruction, preparatory for the university, and for the elements of some other sciences useful in ordinary life to those who do not aim at an university education; and lastly the University. Selections too were proposed to be made from the poor, but promising subjects of the primary schools, to be sent at the public expence to the intermediate colleges, and re-selections from among these again who should have their education compleated, in like manner gratis, at the University. This last institution is the only one which can be said to be in a promising train. The middle grade of instruction is, as yet, left to private enterprise; and the plan adopted for primary schools, very different from what I had proposed, is found so absolutely inefficient that after having wasted on it 45 M. D. a year for five years, it must be abandoned, and some better one substituted. in our plan of the University, we have blended agriculture among the duties of one of the professors of the natural sciences. But our agricultural societies are proposing to give up their funds for the establishment of a distinct professorship for that important science; and with that will probably be incorporated something of the plan of Fellenberg in Switzerland*, engaging youths of the poorer class, who will perform the labours of the farm in the intervals of recieving other instruction in the schools analogues to their vocation. The jealous of our religious sects has forbidden the public authorities to take under their direction the religious instruction of our youth. We have therefore invited them to fix their schools of divinity on the confines of the University, within reach of the other sciences, so necessary to place the clerical order on an equal line of respect with the other learned professions.

The university is but one part of a general plan which I proposed to our legislature five and forty years ago. I need not detail to you the historical circumstances which, till lately, have prevented our entering on it. That proposed the establishment of primary schools in words to be laid off about 5. or 6. miles square, intermediate colleges in large districts, distributed over the state, for the languages, and other instruction, preparatory for the university, and for the elements of some other sciences useful in ordinary life to those who do not aim at an university education; and lastly the University. Selections too were proposed to be made from the poor, but promising subjects of the primary schools, to be sent at the public expence to the intermediate colleges, and re-selections from among these again who should have their education compleated, in like manner gratis, at the University. This last institution is the only one which can be said to be in a promising train. The middle grade of instruction is, as yet, left to private enterprise; and the plan adopted for primary schools, very different from what I had proposed, is found so absolutely inefficient that after having wasted on it 45 M. D. a year for five years, it must be abandoned, and some better one substituted. in our plan of the University, we have blended agriculture among the duties of one of the professors of the natural sciences. But our agricultural societies are proposing to give up their funds for the establishment of a distinct professorship for that important science; and with that will probably be incorporated something of the plan of Fellenberg in Switzerland*, engaging youths of the poorer class, who will perform the labours of the farm in the intervals of recieving other instruction in the schools analogues to their vocation. The jealous of our religious sects has forbidden the public authorities to take under their direction the religious instruction of our youth. We have therefore invited them to fix their schools of divinity on the confines of the University, within reach of the other sciences, so necessary to place the clerical order on an equal line of respect with the other learned professions.

We are disappointed in recieving the last donation of our legislature of 50. M. D. for the purchase of a library and apparatus; the contingency failing on which it depended. We hope they will make it good at their next section; but in the mean time we set out under the disadvantage of great defect in these two important articles. Letters from our academical envoy in England, when he had had time only to augur the prospects before him, are as encouraging as could be anticipated.

We are disappointed in recieving the last donation of our legislature of 50. M. D. for the purchase of a library and apparatus; the contingency failing on which it depended. We hope they will make it good at their next section; but in the mean time we set out under the disadvantage of great defect in these two important articles. Letters from our academical envoy in England, when he had had time only to augur the prospects before him, are as encouraging as could be anticipated.

I have thus given you, Sir, as full a view of our incipient institutions for the education of our citizens as can yet be given. Much is still to be filled up of the remaining chapters of their history, of which a few verses only will be included to the eye and age of 81.

I thank you for the report on the deaf and dumb, nothing can interest more the feelings of benevolence. Age, as well as accident has rendered writing, to me, so laborious and painful, that I decline it as much as possible. But the subject of your letter lies so very near my heart that I must offer it as an apology for so lengthy an answer. With every wish therefore for the prosperity of your undertaking, be please to accept the assurance of my great esteem and respectful consideration.

Th. Jefferson

[Docketed] Th. Jefferson. Monticello aug.t 15. 824. rec’d 21.st

*Philipp Emanuel von Fellenberg was a Swiss philanthropist and educational reformer. Fellenberg founded a school to educate poor children in both agriculture and academics, and he worked to raise the living conditions of the poor to a status closer to that of the upper class.

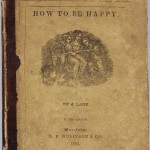

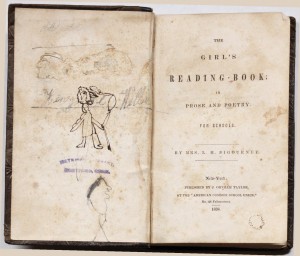

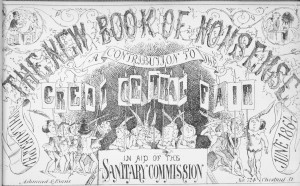

While scrutinizing extended spines on the shelves beneath the Watkinson, lost in the Dewey decimal system, I stumbled across the New Book of Nonsense. I almost overlooked this gem of cynical criticism, as it was not the volume I had been pursuing. I was pleasantly surprised by the crass drawings and captions included within.

While scrutinizing extended spines on the shelves beneath the Watkinson, lost in the Dewey decimal system, I stumbled across the New Book of Nonsense. I almost overlooked this gem of cynical criticism, as it was not the volume I had been pursuing. I was pleasantly surprised by the crass drawings and captions included within. Page 5 – There was a young lady who said “I seldom wear hair on my head; I carry my locks about in a box, For such is the fashion” she said.

Page 5 – There was a young lady who said “I seldom wear hair on my head; I carry my locks about in a box, For such is the fashion” she said. Page 7 – There was a young lady of Cork, Who partook of her soup with a fork, “If I eat it like that I Shall never get Fat!” Said this cleaver young lady of Cork.

Page 7 – There was a young lady of Cork, Who partook of her soup with a fork, “If I eat it like that I Shall never get Fat!” Said this cleaver young lady of Cork. Page 9 – There was an old man of the plains, Who said, “I believe that it rains;” So he buttoned his coat, and got into a boat To wait for a flood on the plains.

Page 9 – There was an old man of the plains, Who said, “I believe that it rains;” So he buttoned his coat, and got into a boat To wait for a flood on the plains. Page 11 – There was a young girl who wore bows, Who said, “if you choose to suppose This hair is all mine, You are wrong I opine, And you can’t see the length of your nose.”

Page 11 – There was a young girl who wore bows, Who said, “if you choose to suppose This hair is all mine, You are wrong I opine, And you can’t see the length of your nose.” Page 14 – There was a dear lady of Eden, Who on apples was quite fond of feedin, So she gave one to Adam, Who said, “thank you madam,” And so they both skedaddled from Eden.

Page 14 – There was a dear lady of Eden, Who on apples was quite fond of feedin, So she gave one to Adam, Who said, “thank you madam,” And so they both skedaddled from Eden. Page 17 – There was an odd man of Woonsocket, who carried bomb-shells in his pocket; Endeavoring to cough one day – they went off, and of course, up he went like a rocket.

Page 17 – There was an odd man of Woonsocket, who carried bomb-shells in his pocket; Endeavoring to cough one day – they went off, and of course, up he went like a rocket. Page 19 – An innocent stranger asked, “where Is the funniest place in the fair?

Page 19 – An innocent stranger asked, “where Is the funniest place in the fair? Page 30 – There was an old man and his wife, who lived in the bitterest strife: He opened the stove, pushed her in with a shove, And cried “there! you pest of my life.”

Page 30 – There was an old man and his wife, who lived in the bitterest strife: He opened the stove, pushed her in with a shove, And cried “there! you pest of my life.” Page 31 – There was a young student at Yale, Who became thin, abstracted and pale; His friends said it was drinking, He declared it was thinking, But one can’t believe students at Yale.

Page 31 – There was a young student at Yale, Who became thin, abstracted and pale; His friends said it was drinking, He declared it was thinking, But one can’t believe students at Yale. Page 43 – There was a prodigious young fop, dressed to kill from the foot to the top: All the girls at the Fair could do nothing but stare And keep clear of that killing young fop.

Page 43 – There was a prodigious young fop, dressed to kill from the foot to the top: All the girls at the Fair could do nothing but stare And keep clear of that killing young fop. Page 53 – My good Southern Brother look here, one thing to y mind is quite clear If we put out this Furness, it no longer will burn us, Nor warm little darkies up here.

Page 53 – My good Southern Brother look here, one thing to y mind is quite clear If we put out this Furness, it no longer will burn us, Nor warm little darkies up here.