[Posted by Mollie Hantman-Weill for ENG 812 Modern Poetry, Professor Rosen]

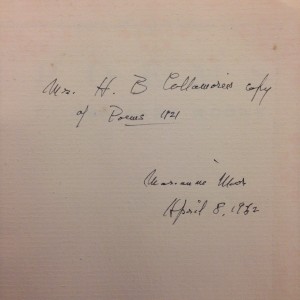

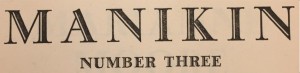

At only a few inches tall and a few millimeters wide, Monroe Wheeler’s Manikin Number Three, a printing of Marianne Moore’s poem “Marriage,” is tiny and unassuming. The copy was presented to me in a red cover with an envelope taped to the inside binding. Once opened, the envelope reveals the small copy of Marianne Moore’s work. The cover is bright blue, with a Greco-Roman style depiction of a scene from Homer’s The Odyssey. Printed in 1923, this is one of 200 copies that were produced. Monroe Wheeler, a publisher and New York native, had previously published Manikin Number One, a very small collection of poetry by Janet Lewis, and Manikin Number Two, a printing of William Carlos Williams poem “Go Go” only months earlier. Harry Bacon Collamore, a lover of poetry, who gave many books of poetry to the library, donated this copy of Manikin Number Three to the Watkinson Library.

At only a few inches tall and a few millimeters wide, Monroe Wheeler’s Manikin Number Three, a printing of Marianne Moore’s poem “Marriage,” is tiny and unassuming. The copy was presented to me in a red cover with an envelope taped to the inside binding. Once opened, the envelope reveals the small copy of Marianne Moore’s work. The cover is bright blue, with a Greco-Roman style depiction of a scene from Homer’s The Odyssey. Printed in 1923, this is one of 200 copies that were produced. Monroe Wheeler, a publisher and New York native, had previously published Manikin Number One, a very small collection of poetry by Janet Lewis, and Manikin Number Two, a printing of William Carlos Williams poem “Go Go” only months earlier. Harry Bacon Collamore, a lover of poetry, who gave many books of poetry to the library, donated this copy of Manikin Number Three to the Watkinson Library.

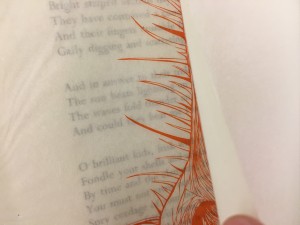

The font is particularly interesting. The cover and title page is printed in a type set called Narcissus Roman, named after the hunter of the Greek myths, and was invented by Walter Tiemann in 1921, two years before Wheeler’s publication. This font was commissioned for a sandpaper company and was inspired by a series of ornamental inline capitals first made in 1745 in France. Narcissus Roman aims to inspire thoughts of early 1700’s era Paris, and of Louis XVI. This typeset is also credited for sparking the revival of 18th century Parisian-style typography in 1920’s America.

The font is particularly interesting. The cover and title page is printed in a type set called Narcissus Roman, named after the hunter of the Greek myths, and was invented by Walter Tiemann in 1921, two years before Wheeler’s publication. This font was commissioned for a sandpaper company and was inspired by a series of ornamental inline capitals first made in 1745 in France. Narcissus Roman aims to inspire thoughts of early 1700’s era Paris, and of Louis XVI. This typeset is also credited for sparking the revival of 18th century Parisian-style typography in 1920’s America.

The first few pages of the printing are not bound to the rest of the pages. Glenway Wescott, American poet (though an expatriate living in Paris for much of his life) wrote a few hundred words on Marianne Moore to be included in Manikin Number Three. Why Wescott? As it turns out, Wescott and Wheeler were dating for much of their lives, the relationship not ending until Wescott’s death. Wheeler must have convinced his boyfriend to write a forward for his publication. Wescott’s introduction, called “Miss Moore’s Observations,” is a slightly rambling, four page compliment of Moore’s work. He speaks to Moore’s talent, even going so far to recommend the reader other poems by Marianne Moore he thinks they would enjoy. My favorite except of his writing is as follows:

An untrampled field of experience presents itself to Miss Moore’s unquailing mild untroubled stare. She has then, naturally enough, no desire to be radical or secretive in her meaning. She wishes to convey or evoke. If the idea and its emotion seem obscure to anyone it is because they are unusual. I have a friend to whom no concept seems single and unified which is not made up of components joined in a familiar way by familiar desires or drama. Those who miscomprehend Miss Moore, unless they are wholly indolent, are like him. So much for the ‘meaning.’

The poem is printed following Wescott’s introduction. At the end of the poem, Marianne Moore signed and dated the copy (November 7, 1953). I am confident that if she had seen any misprints in the poem, she would have corrected them when she signed it, but, as there were not marks on the copy other than the signature, we can assume that the poem was printed exactly as she wanted it to be. I do not know why Wheeler choose this specific poem to be the only Moore poem to print, besides that it is an excellent work, but one guess is the length of the poem. “Marriage” is close to three hundred lines long, making it just long enough for the print to be substantial without needing multiple poems, which would make it a collection.

The copy ends with a quote, chosen by Wheeler, from The Anatomy of Melancholy by Robert Burton, published in 1621. The quote reads, “Even so might Virginia, and those wild Irish have been civilized long since, if that order had been hitherto taken, which now begins, of planting colonies, etc.” Below that is the price of the item, circa-1923, and Monroe Wheeler’s street address. Today, this copy would be sold from anywhere between four hundred dollars to one thousand dollars, depending on condition and whether or not it was signed.

The copy ends with a quote, chosen by Wheeler, from The Anatomy of Melancholy by Robert Burton, published in 1621. The quote reads, “Even so might Virginia, and those wild Irish have been civilized long since, if that order had been hitherto taken, which now begins, of planting colonies, etc.” Below that is the price of the item, circa-1923, and Monroe Wheeler’s street address. Today, this copy would be sold from anywhere between four hundred dollars to one thousand dollars, depending on condition and whether or not it was signed.