[Posted by Kelly Vaughan, for prof. Chris Hager’s course, ENGL 329: Civil War Literature]

“The Yearning of his Heart for His Loved Ones:” Perspectives of Freedom and Marriage from Former Slaves Peter and Vina Still

The Kidnapped and the Ransomed: Being the Personal Recollections of Peter Still and his wife “Vina,” after Forty Years of Slavery describes the life of Peter and Vina Still. Peter was a former enslaved man who lived in Kentucky and Alabama and attempted to collect money to purchase his wife from her master after successfully purchasing, and thus freeing, himself.[1] Peter Still was kidnapped as a young boy when he was living in New Jersey and enslaved in the South for forty years, where he met his wife, Vina, and had children with her. Still was a slave for 40 years when he was able to escape to Philadelphia through use of the Underground Railroad. When he arrived in Philadelphia, he not only coincidentally reunited with his biological brother, William, but formed an alliance with a white abolitionist named Seth Cocklin. After Still raised $5,000 in hopes of purchasing his wife and children back, Cocklin aided Peter in his rescue attempt. During their travels from Philadelphia to Alabama, Cocklin, who was impersonating a slave holder, was caught alone from Still and arrested, and soon after killed.[2] This is one example of the measures abolitionists would take in order to aid runaway slaves.

The Kidnapped and the Ransomed: Being the Personal Recollections of Peter Still and his wife “Vina,” after Forty Years of Slavery describes the life of Peter and Vina Still. Peter was a former enslaved man who lived in Kentucky and Alabama and attempted to collect money to purchase his wife from her master after successfully purchasing, and thus freeing, himself.[1] Peter Still was kidnapped as a young boy when he was living in New Jersey and enslaved in the South for forty years, where he met his wife, Vina, and had children with her. Still was a slave for 40 years when he was able to escape to Philadelphia through use of the Underground Railroad. When he arrived in Philadelphia, he not only coincidentally reunited with his biological brother, William, but formed an alliance with a white abolitionist named Seth Cocklin. After Still raised $5,000 in hopes of purchasing his wife and children back, Cocklin aided Peter in his rescue attempt. During their travels from Philadelphia to Alabama, Cocklin, who was impersonating a slave holder, was caught alone from Still and arrested, and soon after killed.[2] This is one example of the measures abolitionists would take in order to aid runaway slaves.

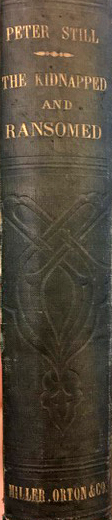

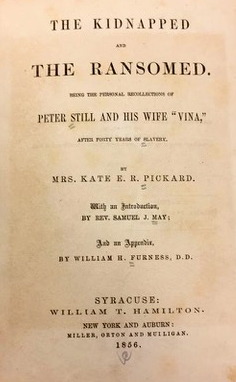

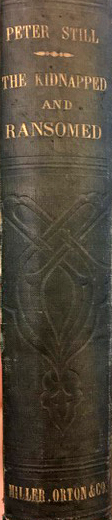

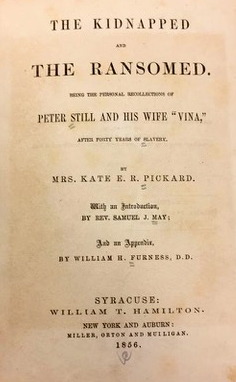

While the transcription of this particular narrative exists online, the original copy exists in Trinity College’s Watkinson Library. This book was published in 1856 by William T. Hamilton in Syracuse, five years before the Civil War started. The book, which is bound in an evergreen colored cover, is 409 pages long, with advertisements for other published slave narratives at the end, including the notable Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years A Slave. The book itself is not large, no more than approximately 6”w x 8”h.

This particular narrative is unique among the majority of slave narratives because it was not actually written by Still himself. Still told his story to Kate E.R. Pickard, who then transcribed Still’s story into this biography.[3] The entire collection of narratives introduces other characters in their life (particularly the numerous slave masters both Peter and Vina had), the early days when Peter was sold repeatedly to different plantations, Vina’s life on the plantation, the momentous moment when Peter purchased himself and traveled to Philadelphia where freedom was waiting for him, and in the final Chapter 37, the reunion between Peter and Vina. The introduction to the text, written by a Unitarian minister by the name of Samuel May, provides a short biography of Kate Pickard and her personal relationship with Peter Still. Pickard was a schoolteacher living in the same vicinity where Peter and Vina were enslaved; Peter would occasionally assist in the same offices Pickard was working in. There, she developed a fondness for his cheerful spirit and polite tone. She was moved by his grit and aimed to use this narrative as a platform to share the humanity and humble love many slaves like Peter had. Additionally, May writes in his introduction that this narrative intends to illustrate:

all the qualities of our common, and of our uncommon humanity–persistence in the pursuit of a desired object; ingenuity in the device of plans for its attainment; self-possession and self-command that can long keep a cherished purpose unrevealed; a deep, instinctive faith in God; a patience under hardship and hope deferred, which never dies; and, withal, a joyousness which, like a life-preserver, bears one above the dark waves of unparalleled trouble.[4]

May addresses the contested moral underpinnings of slavery and reinforces the importance of faith and a strong relationship with God among slaves.

May addresses the contested moral underpinnings of slavery and reinforces the importance of faith and a strong relationship with God among slaves.

“The Marriage” highlights fifteen-year-old Vina’s loneliness as a slave on Mr. McKiernan’s plantation. For her, marriage to Peter would provide a companion, despite her young age. Kinship and procreation was one of the most popular motivations for slaves to marry, as well as the opportunity to strengthen one’s Christian faith. After they married, Peter ran away to the North, freeing himself and then dedicating his time as a free man to designing a plot that would save Vin and their family. Through this narrative, readers learn about the difficulty and repetitive nature of slaves being separated; however, Vina’s marriage provided her with fulfillment rather than anguish, despite their physical separation at the time. Pickard also emphasizes that Peter felt he had never received anything for himself before, despite his work ethic and impressive behavior. Historian Tera Hunter writes that slaves “lived under the auspices of masters who controlled the terms of their most intimate relationships,” including marriage.[5] This highlights the political and personal autonomy of slaves prior to the Civil War.

Since Peter was noted as being favored by Vina’s master, it is unsurprising that they were granted permission to marry. Theoretically, their master could threaten to separate them if they behaved poorly. However, a marriage would be beneficial to a slaveholder if the couple procreated and raised children who could become slaves in just a few short years. In the beginning of “The Marriage” chapter, Pickard describes waiting for the right moment in which Vina and Peter could pursue marriage. Their families were close, which Pickard notes was a rarity for slaves, even those who were just a couple of miles away. Vina found companionship in Peter, and the two, according to Pickard, “waited for a favorable opportunity to be united in marriage.”[6] Peter felt he deserved to be married and have a partner like Vina, for he had been a dedicated servant and was consistently “bright [and] good-humored” when visiting Mr. and Mrs. McKiernan’s plantation, where Vina was in servitude.[7]

Pickard’s narrative is both syntactically attractive and deeply galvanizing to readers. She describes Peter and Vina in very different ways, highlighting Peter’s personal strength and cheerfulness (“a fine, cheerful fellow”), while painting Vina as the scared, lonely young slave (“a timid, shrinking maiden”).[8] Pickard also emphasizes their age difference (Vina was 10 years younger than Peter when they married), so as to show that Peter will be the savior of Vina’s fate. Today, scholars understand expectations and possibilities for slaves depending on their gender. Historian Eric Foner argues that predominantly single, male slaves were the most likely to successfully escape:

Most fugitives…were young men who escaped alone. Those with immediate families often sought to retrieve their wives and children after reaching the North. Some, like Douglass, planned for months; others, like Pennington, decided to run away because of an immediate grievance—in his case, his owner’s threat to whip his mother for insubordination.[9]

With this in mind, it is less surprising that Peter was able to escape, save Vina, and was later shaped as the hero of his own narrative. Runaway slaves were, in some ways, responsible for their own emancipation. Marriage provided a form of limited freedom for enslaved blacks, as it allowed them to gain access to love and family. While they were not physically free for as long as they were enslaved on a plantation, their bargaining with slave masters for marriage helped them to achieve a form of freedom.

The Kidnapped and the Ransomed reveals the experience of a runaway slave and the measures runaways would go to in order to reunite themselves with their family. The unique perspective of this narrative (biographical, rather than autobiographical) provides another lens for analysis. How would the narrative have changed had it been written from the perspective of Vina, rather than Peter, who was noted as more bleak of the two? Would the perseverance and faith engrained in Peter materialize in this narrative? Runaway slave narratives like Still’s served as a vehicle for protest and galvanized other abolitionists at this time. An understanding of the human experience is crucial to understanding the political landscape of the Civil War and a sense of historical empathy.

[1] Pickard, Kate E. R, and William Henry Furness. The Kidnapped and the Ransomed: Being the Personal Recollections of Peter Still and His Wife “Vina,” After Forty Years of Slavery. W.T. Hamilton, 1856.

[2] “Peter Still’s Story.” PBS, Web. http://www.pbs.org/black-culture/shows/list/underground-railroad/stories-freedom/peter-stills-story/

[3] Pickard, Kate E.R. “The Kidnapped and The Ransomed.” The Gilder Lehrman Collection, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, New York. Web. https://www.gilderlehrman.org/collections/c8c88624-a3d5-4a3d-b650-556295771204

[4] Pickard: xxi-xxii

[5] Hunter, Tera. “Putting an Antebellum Myth About Slave Families to Rest.” The New York Times. Web. 13 Mar. 2016.

[6] Pickard: 109

[7] Pickard: 108

[8] Pickard: 108

[9] Foner, Eric. Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad. W. W. Norton & Company, 2015, New York. p. 5

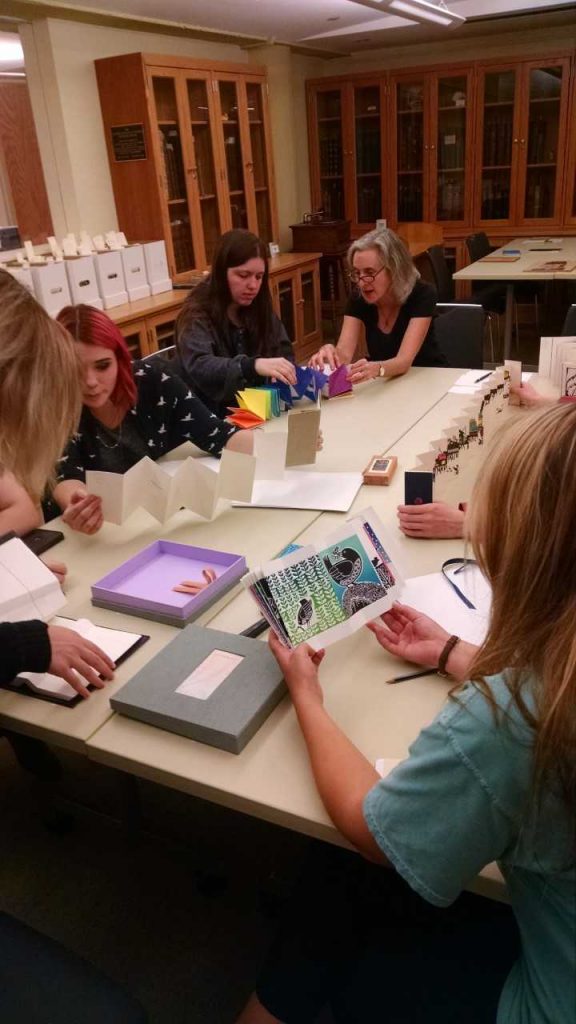

On September 19 I brought my class of 8 Book Arts I students from Hartford Art School to visit the Watkinson Library. I had asked Associate Curator Sally Dickinson to put together a presentation of some history of the book as well as a good selection of contemporary accordion and codices. Her choices for the history of the book really impressed the students. A cuneiform tablet, with magnifying glass for closer examination was passed around and elicited comments “This is so cool” and “Wow!” The more worn, and even rotting, a book appeared the more they were curious about it. After washing our hands, we were also allowed to handle the contemporary books. As my students will be creating their own unique hand bound books with images and text, this was a special opportunity to see how other artists combine structure and content in a variety of ways. An hour and a half was the perfect amount of time to visit. Many thanks to Sally for this unique opportunity.

On September 19 I brought my class of 8 Book Arts I students from Hartford Art School to visit the Watkinson Library. I had asked Associate Curator Sally Dickinson to put together a presentation of some history of the book as well as a good selection of contemporary accordion and codices. Her choices for the history of the book really impressed the students. A cuneiform tablet, with magnifying glass for closer examination was passed around and elicited comments “This is so cool” and “Wow!” The more worn, and even rotting, a book appeared the more they were curious about it. After washing our hands, we were also allowed to handle the contemporary books. As my students will be creating their own unique hand bound books with images and text, this was a special opportunity to see how other artists combine structure and content in a variety of ways. An hour and a half was the perfect amount of time to visit. Many thanks to Sally for this unique opportunity.