It seems that Lydia Sigourney’s destiny had always been to teach; whether in person or through her writing, her life followed an instructive path from her youth. As a child, she often “played school with her dolls ‘reproving their faults, stimulating them to excellence, and enforcing a variety of moral obligations’ “ (DeLong 36). She continued to teach into early adulthood and to employ didactic tactics in her writing, much of which was aimed at a young audience and carried messages of conduct, religion, and morals. Five of Sigourney’s books containing such messages are described below. These five, however, do not comprise an all-inclusive list; many more of her books contain similar messages aimed at children and adults alike.

It seems that Lydia Sigourney’s destiny had always been to teach; whether in person or through her writing, her life followed an instructive path from her youth. As a child, she often “played school with her dolls ‘reproving their faults, stimulating them to excellence, and enforcing a variety of moral obligations’ “ (DeLong 36). She continued to teach into early adulthood and to employ didactic tactics in her writing, much of which was aimed at a young audience and carried messages of conduct, religion, and morals. Five of Sigourney’s books containing such messages are described below. These five, however, do not comprise an all-inclusive list; many more of her books contain similar messages aimed at children and adults alike.

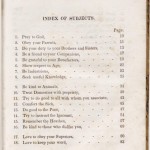

Her blatantly instructive book, How to Be Happy, provides

Her blatantly instructive book, How to Be Happy, provides  a gender-neutral formula for success and happiness in life that carries many messages similar to those conveyed in her books for boys and girls. She illustrates the method of proper treatment for a variety of individuals, including one’s parents, siblings, and elders.

a gender-neutral formula for success and happiness in life that carries many messages similar to those conveyed in her books for boys and girls. She illustrates the method of proper treatment for a variety of individuals, including one’s parents, siblings, and elders.

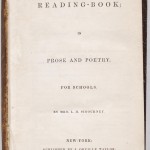

Sigourney’s writing for boys was different than most of the popular literature written for them at the time. It demonstrated a need for boys to become men with “a home-centered value system that endorsed masculine self-sacrifice and social obligation” (Parille 5). In her book, The Boy’s Reading Book; in Prose and Poetry, for Schools, the passage titled “Good Manners” outlines the benefits of proper behavior and the need for it. She also says that a man without manners is “an offense to the Almighty,” and good manners “must be worn as daily apparel, not as a suit for company” (Sigourney, The Boy’s Reading 114-115).

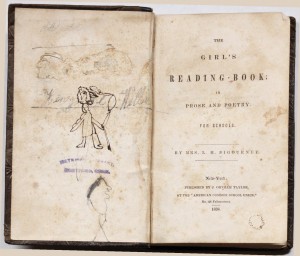

In The Girl’s Reading-Book; in Prose and Poetry. For Schools, Sigourney includes passages titled “Order,” “The Good Daughter,” and “Procrastination.” In the passage entitled “Order,” emphasis is placed on the necessity of having a proper place for things, and life without order is compared to having “wise laws, and paying no regard to them” (Sigourney, The Girl’s Reading 19). She explains that if these bad habits are established as a child, they will carry on into adulthood and cause irreparable damage to one’s reputation and temperament. “Procrastination,” a poem, warns of the repercussions of idle waiting. Sigourney describes various aspects of nature, such as the bird in flight or the running stream, and explains to the reader that should you ask such things to stop and wait, they would answer, “’A future day is not our own’” (181). Her final warning is that one must do “what thy duty dictates, do” and “delay no longer” for fear that death is upon us at each moment in our lives.

In The Girl’s Reading-Book; in Prose and Poetry. For Schools, Sigourney includes passages titled “Order,” “The Good Daughter,” and “Procrastination.” In the passage entitled “Order,” emphasis is placed on the necessity of having a proper place for things, and life without order is compared to having “wise laws, and paying no regard to them” (Sigourney, The Girl’s Reading 19). She explains that if these bad habits are established as a child, they will carry on into adulthood and cause irreparable damage to one’s reputation and temperament. “Procrastination,” a poem, warns of the repercussions of idle waiting. Sigourney describes various aspects of nature, such as the bird in flight or the running stream, and explains to the reader that should you ask such things to stop and wait, they would answer, “’A future day is not our own’” (181). Her final warning is that one must do “what thy duty dictates, do” and “delay no longer” for fear that death is upon us at each moment in our lives.

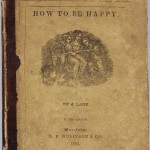

Letters to Young Ladies and Letters to Mothers include similar messages, catered to women of the age group indicated by each title. In Letters to Young Ladies, Sigourney discusses the upbringing of young women. Some of the contents include: “Manners and Accomplishments,” “Friendship,” and “Self-Control.” In the section titled “Manners and Accomplishments,” she argues that manners are more important than things like dress or beauty because manners are “more permanent, and more certain in their results” (Sigourney, Letters to Young 105). In Letters to Mothers, some of the contents include: “Idiom of Character,” “Duty to the Community,” and “Hospitality.” In the passage “Duty to the Community,” Sigourney states that she feels “peculiar solicitude with regard to the manner in which our daughters are reared. … they are emphatically our representatives” (Letters to Mothers 170). Throughout the passage, she describes the importance of education for girls and the need for their mothers to be careful not to allow their daughters to indulge in “elaborate dress, and fashionable parties.”

In addition to the didactic endeavors of the five books mentioned previously, Sigourney worked to deliver her messages in person as a teacher in both Norwich and Hartford, Connecticut. After coming to Hartford to stay with the Wadsworth family, Daniel Wadsworth suggested that she start a school for girls in his mother’s home. One of Sigourney’s students was a young deaf girl, Alice Cogswell. Alice’s family worked hard to ensure that her life was as normal and fulfilling as possible despite her handicap, and Sigourney did the same. She worked closely with Alice to teach her to read and write and was the first person in the United States to teach a prelingually deafened child to read and write. While she was working with Alice, Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, a recent graduate from Andover seminary school, was working with Laurent Clerc, a deaf Frenchman, to learn sign language. In 1817, Gallaudet returned to the United States with his new knowledge and Clerc as his partner. Together they opened the first school for the deaf in the U.S.; it was located in Hartford. It has been argued, “that these two men would never have been called on to play the roles they did without the earlier and necessary contributions of Lydia Huntley Sigourney” (Sayers and Gates 369).

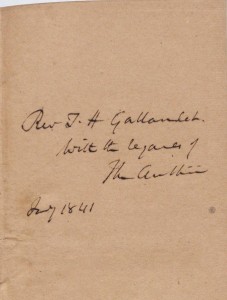

Years after her work with Alice and the opening of the school, Sigourney gave Gallaudet a signed copy of her book, Memoir of Mrs. Hooker, in 1841. The role of these three individuals, and especially of Lydia Sigourney, changed the opportunities available for deaf people in the United States. Her dedication to teaching and pure-minded motives allowed her to see past Alice’s handicap and to provide her with a challenging education. As with her childhood dolls, Sigourney sought to stimulate each of her students to excellence despite their differences.

Years after her work with Alice and the opening of the school, Sigourney gave Gallaudet a signed copy of her book, Memoir of Mrs. Hooker, in 1841. The role of these three individuals, and especially of Lydia Sigourney, changed the opportunities available for deaf people in the United States. Her dedication to teaching and pure-minded motives allowed her to see past Alice’s handicap and to provide her with a challenging education. As with her childhood dolls, Sigourney sought to stimulate each of her students to excellence despite their differences.

[Posted by Erika Jenns, Indiana University ’13]

Works Cited

Parille, Ken. “What Our Boys Are Reading.” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly 33.1 (2008): 4-25. PDF file.

Sayers, Edna Edith and Diana Gates. “Lydia Huntley Sigourney and the Beginnings of American Deaf Education in Hartford: It Takes a Village.” Sign Language Studies, 8.4, (2008): 369-411. PDF file.

Sigourney, Lydia H. The Boy’s Reading Book; in Prose and Poetry, for Schools. New York: J. Orville Taylor, 1839. Print.

—. The Girl’s Reading-Book; in Prose and Poetry. For Schools. New York: J. Orville Taylor, 1839. Print.

—. Letters to Young Ladies. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1837. Print.

—. Letters to Mothers. New York: Harper & Brothers. 1839. Print.