[Posted by Erika Jenns, Indiana University ’13]

Soft sod crinkles beneath my tiptoeing feet as I quietly approach her resting place. Gripping prickling stems against my right palm, foliage meant to be a tribute to the long forgotten poetess whose life and collected works I have spent the last six weeks scrutinizing: Lydia H. Sigourney. The 206 gilt bindings that enclose her poetry, prose, and personal inscriptions occupy a substantial space beneath the Watkinson, and their finer details have taken residence in my memory.

Soft sod crinkles beneath my tiptoeing feet as I quietly approach her resting place. Gripping prickling stems against my right palm, foliage meant to be a tribute to the long forgotten poetess whose life and collected works I have spent the last six weeks scrutinizing: Lydia H. Sigourney. The 206 gilt bindings that enclose her poetry, prose, and personal inscriptions occupy a substantial space beneath the Watkinson, and their finer details have taken residence in my memory.

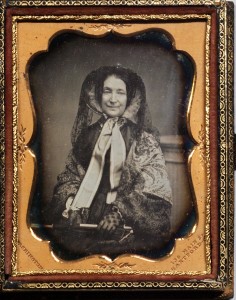

Looking down at her grave, I picture her as she was in her 1852 daguerreotype by Augustus Washington; an image enclosed in elegant black box, titled “Friendships Offering.” Washington, an African American daguerreotypist and Hartford resident, captured Sigourney in stylish garb including an elaborate bonnet and lace. The stern smirk she addresses the camera with reminds me of her prose pieces regarding proper dress and behavior such as, How to Be Happy, The Girl’s Reading Book, and Letters to Young Ladies. She speaks to her reader as a mother would to a child, and in her daguerreotype she looks upon her viewer in the same manner.

Looking down at her grave, I picture her as she was in her 1852 daguerreotype by Augustus Washington; an image enclosed in elegant black box, titled “Friendships Offering.” Washington, an African American daguerreotypist and Hartford resident, captured Sigourney in stylish garb including an elaborate bonnet and lace. The stern smirk she addresses the camera with reminds me of her prose pieces regarding proper dress and behavior such as, How to Be Happy, The Girl’s Reading Book, and Letters to Young Ladies. She speaks to her reader as a mother would to a child, and in her daguerreotype she looks upon her viewer in the same manner.

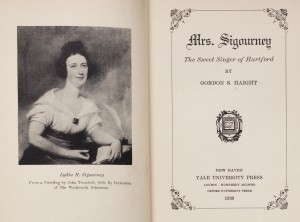

As I reflect on her life, I consider two contradictory sources: Sigourney’s autobiography, Letters of Life, and Gordon Haight’s biography, Mrs. Sigourney The Sweet Singer of Hartford. Sigourney enjoyed much fame during her lifetime but was forgotten soon after her death. She wrote her autobiography before her death, and it was published posthumously in 1866. Sixty-five years later, Gordon Haight published his biography.

Letters of Life makes use of a casual and personal approach to the description and recreation of Sigourney’s life events. It is written as if she is writing a letter to a friend, and the tone she uses is much like that used in her prose and poetry. She describes her experience writing as a professional to her reader, “My literary course has been a happy one. It commenced in impulse, and was continued from habit.” Sigourney was well known in the 19th century and widely appreciated as a writer, but her fame faded quickly after her death. Her rapid decline is intriguing, and Gordon Haight would have his readers believe that it was a result of the content of Sigourney’s poetry. She was too sentimental. Sigourney’s sentimentality can be seen in her autobiography as she describes her first loss, “My fourteenth birthday had scarce added itself like a pearl to the necklace of life, when the shadow of a great grief came upon me.” Sigourney was consistently able to eloquently describe her experiences with death, a talent that made her a popular choice for memoirs and elegies. “Indeed, it could be said that in her day one had not definitely died in Hartford until Lydia Sigourney had written one’s elegy.”

Letters of Life makes use of a casual and personal approach to the description and recreation of Sigourney’s life events. It is written as if she is writing a letter to a friend, and the tone she uses is much like that used in her prose and poetry. She describes her experience writing as a professional to her reader, “My literary course has been a happy one. It commenced in impulse, and was continued from habit.” Sigourney was well known in the 19th century and widely appreciated as a writer, but her fame faded quickly after her death. Her rapid decline is intriguing, and Gordon Haight would have his readers believe that it was a result of the content of Sigourney’s poetry. She was too sentimental. Sigourney’s sentimentality can be seen in her autobiography as she describes her first loss, “My fourteenth birthday had scarce added itself like a pearl to the necklace of life, when the shadow of a great grief came upon me.” Sigourney was consistently able to eloquently describe her experiences with death, a talent that made her a popular choice for memoirs and elegies. “Indeed, it could be said that in her day one had not definitely died in Hartford until Lydia Sigourney had written one’s elegy.”

Haight’s biography maintains a fairly negative outlook on Sigourney’s writing. He begins by saying, “I hoped to find among her poems some few pieces that would establish her right to the reputation she enjoyed for half a century as America’s leading poetess. But before reading many of the forty-odd volumes through which the search ultimately led me, I was forced to agree that posterity had judged fairly in denying her claim.” Haight goes on to attribute Sigourney’s popularity to her “wide acquaintance with famous people both at home and abroad during a lifetime that stretched from Washington’s second term as President beyond the death of Lincoln.” Other critics have been equally as hard on Sigourney’s writing. Emily Stipes Watts described Sigourney’s work as “padded, pedantic, and prudish.” It may be unfair for modern critics to judge Sigourney’s poetry so harshly considering that the audience has changed dramatically from the time of publication. An appreciative 19th century reader vividly described Sigourney’s reader-base and the usefulness of her poetry in their lives, “[Her poems are] laid on a million of memory’s shelves. Children in our infant schools lisp her mellow canzonets; older youths recite her poems for riper minds in our grammar schools and academies; mothers pore over her pages of prose for counsel, and the aged of either sex draw consolation from the inspirations of her sanctified muse in their declining years.”

Haight’s biography maintains a fairly negative outlook on Sigourney’s writing. He begins by saying, “I hoped to find among her poems some few pieces that would establish her right to the reputation she enjoyed for half a century as America’s leading poetess. But before reading many of the forty-odd volumes through which the search ultimately led me, I was forced to agree that posterity had judged fairly in denying her claim.” Haight goes on to attribute Sigourney’s popularity to her “wide acquaintance with famous people both at home and abroad during a lifetime that stretched from Washington’s second term as President beyond the death of Lincoln.” Other critics have been equally as hard on Sigourney’s writing. Emily Stipes Watts described Sigourney’s work as “padded, pedantic, and prudish.” It may be unfair for modern critics to judge Sigourney’s poetry so harshly considering that the audience has changed dramatically from the time of publication. An appreciative 19th century reader vividly described Sigourney’s reader-base and the usefulness of her poetry in their lives, “[Her poems are] laid on a million of memory’s shelves. Children in our infant schools lisp her mellow canzonets; older youths recite her poems for riper minds in our grammar schools and academies; mothers pore over her pages of prose for counsel, and the aged of either sex draw consolation from the inspirations of her sanctified muse in their declining years.”

Sigourney worked hard in her lifetime to write didactic prose and poetry that was applicable to a large readership. In her book, Letters to Mothers, Sigourney states, “It has been somewhere asserted, that he who would agreeably instruct children, must become the pupil of children. They are not, indeed, qualified to act as guides, among the steep cliffs of knowledge, which they have never traversed. But they are most skilful [sic] conductors to the green plats of turf, and the wild flowers that encircle its base.” Sigourney was a teacher from childhood to adulthood. Her books provide lessons that remain valuable today, and as we navigate the steep cliffs of knowledge, it seems she would be an ideal guide, for we are only fit to frolic among the “green plats of turf and wild flowers at the base.”