Revealing the Object

[Posted by Margaret Pallis, for Prof. David Rosen’s course, “Modern Poetry”]

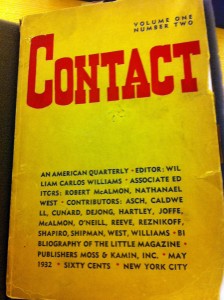

When I searched the Watkinson for an object related to William Carlos Williams’ poetry, I found myself interested in a 1932 edition of Contact, a literary journal first published in December of 1920; three more editions came out in 1921, and a fifth and final edition was published in 1923. In 1932, Williams, this time working with Nathaniel West, revived Contact, renaming it Contact: an American Quarterly Review. However, the revived journal only lasted for a total of three volumes—all of which were published in 1932. The copy I examined at the Watkinson was the second volume of this journal.

When I searched the Watkinson for an object related to William Carlos Williams’ poetry, I found myself interested in a 1932 edition of Contact, a literary journal first published in December of 1920; three more editions came out in 1921, and a fifth and final edition was published in 1923. In 1932, Williams, this time working with Nathaniel West, revived Contact, renaming it Contact: an American Quarterly Review. However, the revived journal only lasted for a total of three volumes—all of which were published in 1932. The copy I examined at the Watkinson was the second volume of this journal.

Part of what initially caught my attention was the quality of the paper. While it was old, certainly, I was more interested in the fact that the paper was not of good quality. The cover of the journal is unassuming, with no frills; however, the font is large and red, which commands attention. There were very few advertisements in the journal, and with a little investigating, I discovered (in correspondence between Williams and Ezra Pound) that Williams had no money with which to pay for submissions to the journal. It appears that neither the venture in the 1920s, nor this 1932 venture, was particularly successful financially.

The volume I examined of Contact includes two poems by Williams: “The Canada Lily” (later renamed “The Red Lily”) and “The Cod Head.” I believe that this was a first publication for both of the poems. Certainly, Contact served as an opportunity for Williams to showcase some of his own poetry. I also discovered, looking through this particular volume, that the journal also contained a continuation of a bibliography of “Little Magazines,” compiled by David Moss. This appears to be one of the first times that such a bibliography was compiled. Each of the three 1932 volumes presented a section of the bibliography, as it was too long to include in one volume.

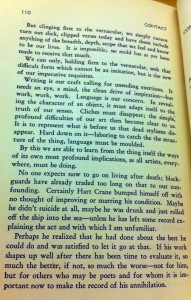

The main reason I selected this particular journal was because of the editorial that Williams included. In the editorial, Williams suggests that the name of the journal encapsulates some of his ideas about poetry. The idea of “contact” for Williams seems to suggest that symbols are no longer relevant, and he invites readers of modern poetry to see the object, instead of what an object may or may not symbolize. In his commentary, Williams articulates his beliefs (about poetry and the role of poetry in our lives) when he suggests that we must come “eye to eye with some of the figures of our country and epoch, truthfully.” He suggests that, “if we cannot find virtue in the object of our lives, then for us there is none anywhere. We won’t solve or discover by using ‘profound’ (and borrowed) symbolism.” The idea of contact seems to be a cutting away of everything unessential, which then creates a new surface which allows for immediate and unmediated contact. We must, says Williams in his commentary, “reveal the object.” Williams argues that the poet must let go of clichés and “dead stylisms.” He argues that writers must “learn from the thing itself.”

The main reason I selected this particular journal was because of the editorial that Williams included. In the editorial, Williams suggests that the name of the journal encapsulates some of his ideas about poetry. The idea of “contact” for Williams seems to suggest that symbols are no longer relevant, and he invites readers of modern poetry to see the object, instead of what an object may or may not symbolize. In his commentary, Williams articulates his beliefs (about poetry and the role of poetry in our lives) when he suggests that we must come “eye to eye with some of the figures of our country and epoch, truthfully.” He suggests that, “if we cannot find virtue in the object of our lives, then for us there is none anywhere. We won’t solve or discover by using ‘profound’ (and borrowed) symbolism.” The idea of contact seems to be a cutting away of everything unessential, which then creates a new surface which allows for immediate and unmediated contact. We must, says Williams in his commentary, “reveal the object.” Williams argues that the poet must let go of clichés and “dead stylisms.” He argues that writers must “learn from the thing itself.”

The commentary also gave me what I suppose I might call an insight in Williams as a person. Toward the end of that piece, he writes about Hart Crane’s suicide. While I was initially struck by what felt like callousness, when Williams writes that “no one expects now to go on living after death; blackguards have already traded too long on that to our confounding. Certainly Hart Crane bumped himself off with no thought of improving or marring his condition.” I may have been startled by the “bumped himself off” when I would, perhaps, have anticipated some sympathy for a troubled man. Instead, I began to see Williams’ point that perhaps Crane had “done about the best he could do and was satisfied to let it go at that.” There is a practical quality to the statement that is, I suppose, satisfying.

The commentary also gave me what I suppose I might call an insight in Williams as a person. Toward the end of that piece, he writes about Hart Crane’s suicide. While I was initially struck by what felt like callousness, when Williams writes that “no one expects now to go on living after death; blackguards have already traded too long on that to our confounding. Certainly Hart Crane bumped himself off with no thought of improving or marring his condition.” I may have been startled by the “bumped himself off” when I would, perhaps, have anticipated some sympathy for a troubled man. Instead, I began to see Williams’ point that perhaps Crane had “done about the best he could do and was satisfied to let it go at that.” There is a practical quality to the statement that is, I suppose, satisfying.