Cadwallader Colden

[Posted by Sarah St. Germain for AMST 838: America Collects Itself: From Colony to Empire]

Cadwallader Colden’s The history of the Five Indian Nations depending on the Province of New-York in America was first published in 1727 and is an important work of history from the colonial period. Colden was a physician, natural scientist, lieutenant governor of New York, and the first representative to Iroquois Confederacy. He was born in 1688 in Scotland and made his way to America in 1710. He wrote essays on the filth of New York City, philosophy, and botany, as well as this important work.

Cadwallader Colden’s The history of the Five Indian Nations depending on the Province of New-York in America was first published in 1727 and is an important work of history from the colonial period. Colden was a physician, natural scientist, lieutenant governor of New York, and the first representative to Iroquois Confederacy. He was born in 1688 in Scotland and made his way to America in 1710. He wrote essays on the filth of New York City, philosophy, and botany, as well as this important work.

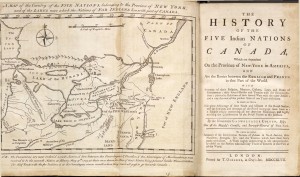

The Watkinson’s copy of The history of the Five Indian Nations was published in London in 1747, which one editor claimed had, “alterations and omissions so numerous , that students to whom these English editions are familiar have really no idea of what the work was as originally written by Colden”. He also notes that George Brinley of Hartford, owned a copy of the original press run. Although the Watkinson owns a portion of his collection, this original copy is not included. The book includes a fold-out map; a dedication; detailed introduction (“being a short view of the form of government of the five nations”); a vocabulary of tribal names; and chapters like, Of the Transactions of the Indians of the Five Nations with the neighbouring English colonies and Mons. De la Barres Expedition and some remarkable transactions in 1684.

Just the Introduction itself is a wealth of information. For instance, Colden notes that the Iroquois:

“Never make any prisoner a slave”

“Keep themselves free of the bondage of wedlock”

“Theft is very scandalous among them”

“Are much given to speech-making”

“Have no kind of publick worship”

“They always dress the corps (sic) in its finery”

The map is fairly detailed and shows the tribes of the New York and Great Lakes region. If you focus on the New York section above “The Countrey of the Five Nations”, you will see each of the five nations spelled out in their territory. If you look closer still, you will see a small building drawn near each. These are what were known to the English as “castles”. In Little Falls, NY, where I grew up, there was a place called Indian Castle Church. It never occurred to me that it was a weird name, or that it had history behind it. “Indian Castle in Danube was so named from the upper Indian castle or fort, built in 1710 on the flat just below the mouth of Nowadaga creek.” -New York State Museum Bulletin, November 1917. This castle is located above the ‘s’ in Mohawkes. Each one of the five nations had a castle.

The map is fairly detailed and shows the tribes of the New York and Great Lakes region. If you focus on the New York section above “The Countrey of the Five Nations”, you will see each of the five nations spelled out in their territory. If you look closer still, you will see a small building drawn near each. These are what were known to the English as “castles”. In Little Falls, NY, where I grew up, there was a place called Indian Castle Church. It never occurred to me that it was a weird name, or that it had history behind it. “Indian Castle in Danube was so named from the upper Indian castle or fort, built in 1710 on the flat just below the mouth of Nowadaga creek.” -New York State Museum Bulletin, November 1917. This castle is located above the ‘s’ in Mohawkes. Each one of the five nations had a castle.

The brief vocabulary section includes many names that are familiar today, though the spellings are very different. It offers words known to the French with an Iroquois interpretation. For instance:

Chigagou (now Chicago): Caneraghik

Detroit: Teuchsagrondie

Manhattan: New York City

Algonkins: Adirondacks

Renards: Quaksies (renard is French for duck so you can see the relationship between the words)

In addition, the dedication alone offers an in-depth look into the politics of the times. Dedicated to “The Honorable General Oglethorpe”, Colden writes, “If care were taken to plant and cultivate [the Iroquois]… they would become a people whose friendship might add honour to the British nation”. In a time before the American Revolution, he clearly believes that the strength of the Iroquois should be harvested to fight (at the time) the French. Later, the Mohawk, Seneca, Onondaga, and Cayuga nations would join the British in the Revolution, while the Oneidas and Tuscaroras (the sixth nation, added in 1723) would join the Americans. Later, he equates the Iroquois with the Romans, saying that to increase their strength as a confederation; they “encourage the People of other Nations to incorporate with them”. “The cruelty the Indians use in their wars… is deservedly indeed held in abhorrence: But whoever reads the history of the famed heroes (the Romans), will find them not much better in this respect.” This is a fairly balanced line for a 17th century writer.

Colden continues with a “short view” of the Iroquois government and then part one, chapter one: From the first Knowledge the Christians had of the Five Nations, to the time of the happy revolution in Great Britain. (Note: Colden uses the word “rodinunchsiouni” as the Iroquois word for their nations. In English today, it is Haudenausaunee, people of the longhouse).

He includes stories of warriors, hunting parties, and expeditions that, “may seem incredible to many” but show “how extreamly revengeful” the Iroquois were. Don’t forget that Colden equated them with the Romans. Much of the book is based on tales of the battles and skirmishes between the Five Nations, the French, the British, and other tribes.

The final portion of the book stems from Colden’s political career: Papers relating to An Act of the Assembly of the Province of New York for Encouragement of the Indian Trade &c and for prohibiting the selling of Indian Goods to the French, viz. of Canada. An incredible lengthy, yet descriptive title. This is comprised of treaties, letters, speeches, and a list of the people who attended a council in Philadelphia in 1742. The spelling of the names of the Indians who were in attendance (from at least 7 different tribes) gives an incredible lesson on language and phonetics. Even today, the Iroquois languages are difficult to read (the pronunciation and the English alphabet aren’t completely compatible. It would be quite a project to sound out the names and try to glean meaning from them).

Cadwallader Colden’s The History of the Five Indian Nations is still used today as a reference for historical books on the Iroquois. His attention to detail and (mostly) balanced writing make it one of the finest books on the topic.