[Posted by Sophie Prince for ENG 812 Modern Poetry, Professor Rosen]

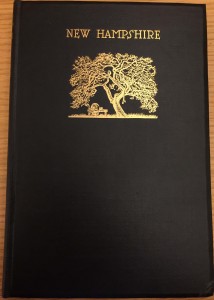

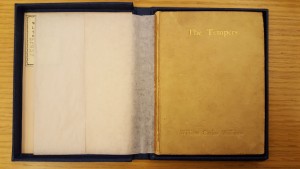

In 1913, Williams Carlos Williams published his second book of poetry, The Tempers, through a small publishing house in London with the help of fellow modern poet, Ezra Pound. Williams was already 30 years old at the time, but this collection was just an early step in his career. A first edition copy of The Tempers, one of only 1000 printed, is preserved at the Watkinson Library in a small, royal blue box.

In 1913, Williams Carlos Williams published his second book of poetry, The Tempers, through a small publishing house in London with the help of fellow modern poet, Ezra Pound. Williams was already 30 years old at the time, but this collection was just an early step in his career. A first edition copy of The Tempers, one of only 1000 printed, is preserved at the Watkinson Library in a small, royal blue box.

The artifact is eye-catching not for its grandeur or style, but because it is so small. At around four and a half inches, the entire book fits in the palm of your hand. Something about its miniature-nature marks the book’s uniqueness and makes it even more enticing to encounter. Other than the blue box (which was likely added by the Watkinson to protect the fragile binding), a plain, beige cover and gold inscription of the title are the only decorations. These stylistic choices seem to speak to Williams as a poet. The simplicity of the edition is a reminder of his domestic and pastoral subjects as well as his emphasis on honesty.

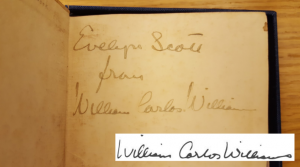

While the outside of the edition already offers reflection on Williams’ career, the inside pages hold many more opportunities to explore his life and poetry. On the very first page, an inscription in loose cursive handwriting and fading, grey ink reads: “To Evelyn Scott from William Carlos Williams.” Discovering Williams’ own signature (here compared side by side to his signature logged at www.poetsquarterly.com) was quite a pleasure. It brought many questions to the imagination, as well as the unique feeling of knowing a celebrated and genius poet held this very book in his own hands. In addition, the signature raises the value of the book immensely. After researching some rare book sellers, it appears that these first edition copies typically sell for around $1000, particularly because few of the original and incredibly fragile copies survived. With the added benefit of Williams’ signature, the selling price of the book goes up to somewhere around $7500. Unfortunately, the condition of the book is relatively poor. The outside edges of the pages where they were folded together during production were not cut open, but forced apart and torn, likely by an eager reader.

While the outside of the edition already offers reflection on Williams’ career, the inside pages hold many more opportunities to explore his life and poetry. On the very first page, an inscription in loose cursive handwriting and fading, grey ink reads: “To Evelyn Scott from William Carlos Williams.” Discovering Williams’ own signature (here compared side by side to his signature logged at www.poetsquarterly.com) was quite a pleasure. It brought many questions to the imagination, as well as the unique feeling of knowing a celebrated and genius poet held this very book in his own hands. In addition, the signature raises the value of the book immensely. After researching some rare book sellers, it appears that these first edition copies typically sell for around $1000, particularly because few of the original and incredibly fragile copies survived. With the added benefit of Williams’ signature, the selling price of the book goes up to somewhere around $7500. Unfortunately, the condition of the book is relatively poor. The outside edges of the pages where they were folded together during production were not cut open, but forced apart and torn, likely by an eager reader.

The handwritten note from Williams raises an important question: who was Evelyn Scott? The answer to this question provides a bit of insight into Williams’ intellectual circle. Evelyn Scott, also known as Elsie Dunn, was an American novelist, playwright, and poet operating in the same period as Williams. At the time, she was an important part of the modernist circle, known for being an experimental writer published in avant-garde magazines. In biographies of Scott, it is always mentioned that William Carlos Williams was one of her many literary friends. Unfortunately, while Williams’ reputation has been cemented as an influential American poet, Scott eventually faded into the background after two decades of literary significance in the 1920s and 30s. The two names contained within this single copy leave much to be explored about the literary circles of the time. It is exciting that this book, a gift from Trinity alum Arthur Miliken, was at one point involved in a personal exchange between two poets.

One more relationship of Williams’ is represented in this edition of The Tempers and it is worth noting. The dedication inside the book is to Carlos Hoheb, Williams’ uncle on his mother’s side. Hoheb was an accomplished Puerto Rican musician and had an influence in Williams’ early life. In the act of declaring Williams as one of the great American poets, his Spanish roots are often forgotten. This dedication reinforces his Spanish-American background and the collection even includes one of his Spanish translations, “El Romancero.”

Overall, the biggest surprise when examining this collection by a proudly American poet was that it was published in London. Even more surprising is the fact that no American edition of The Tempers was ever released. This felt quite contradictory to Williams’ agenda as an American nationalist poet. At the same time, it speaks to the fact that the poetry community was still largely focused around London during this period. It likely felt as a necessary starting point, especially under the advice of Ezra Pound, who made his fame in the literary community of London as an American expatriate.

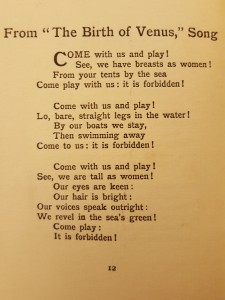

Pound was, in fact, the orchestrator of this publication and Elkins Matthew was his main publisher. After meeting at University of Pennsylvania, Pound became a friend to Williams and helped develop his reputation. But later in their careers, the two poets experienced a polar divide. Williams’ style developed in a way that was distinctly American, felt scorned by Pound, and purposefully excluded himself from the elitist, European poetry community. When looking at The Tempers, the trajectory of the relationship between Pound and Williams serves as an interesting backdrop for examining the poetry. Most of the poems in this volume do not sound anything like the Williams of his later, more successful collection, Spring and All. Poems titled “Con Brio” and “Ad Infinitum” feel much more like the type of poetry Pound would support. The poem, From “The Birth of Venus,” Song, is pictured here as an example of the poetry in this early collection, which is still cemented in the conventional. Knowing that Williams’ brand of experimentation eventually developed in a very unique way, The Tempers provides some interesting insight into his early career and is simply a miniature wonder to investigate.

Pound was, in fact, the orchestrator of this publication and Elkins Matthew was his main publisher. After meeting at University of Pennsylvania, Pound became a friend to Williams and helped develop his reputation. But later in their careers, the two poets experienced a polar divide. Williams’ style developed in a way that was distinctly American, felt scorned by Pound, and purposefully excluded himself from the elitist, European poetry community. When looking at The Tempers, the trajectory of the relationship between Pound and Williams serves as an interesting backdrop for examining the poetry. Most of the poems in this volume do not sound anything like the Williams of his later, more successful collection, Spring and All. Poems titled “Con Brio” and “Ad Infinitum” feel much more like the type of poetry Pound would support. The poem, From “The Birth of Venus,” Song, is pictured here as an example of the poetry in this early collection, which is still cemented in the conventional. Knowing that Williams’ brand of experimentation eventually developed in a very unique way, The Tempers provides some interesting insight into his early career and is simply a miniature wonder to investigate.