[Posted by Henry Arneth, Watkinson staffer]

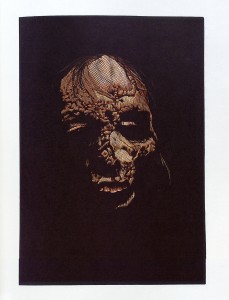

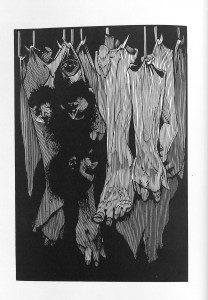

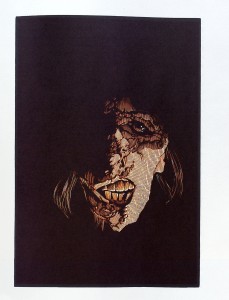

While shelving a book in Watkinson Library, I noticed the 1984 edition of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and immediately thought of the awesome illustrations (woodcuts) by Barry Moser created for this edition. I had first seen the illustrations, separate from the book, when I worked for an auction house and several copies of the woodcuts were being offered to raise funds by a local museum. One of the images that stuck in my mind was of a number of body parts hung on hooks waiting to be used by Doctor Frankenstein. I couldn’t resist. I opened the book; I had to revisit not only the story since it was close to Halloween, but also the woodcuts I enjoyed so much.

After the title page, before the narrative even began, was a quote from Milton across from the image of a tree reminiscent of Yggdrasil, Odin’s tree of knowledge where Huginn (thought) and Muninn (memory) reside in Norse mythology:

“Did I request thee, maker, from my clay / To mould me a man? Did I solicit thee / From darkness to promote me?” [Adam, Paradise Lost (John Milton)]

Then we are left in Mary Shelley’s hands as she takes us on an unforgettable journey…

Then we are left in Mary Shelley’s hands as she takes us on an unforgettable journey…

“My abhorrence of this fiend can not be conceived. When I thought of him, I gnashed my teeth, my eyes became inflamed, and I ardently wished to extinguish that life I had so thoughtlessly bestowed.” [Victor Frankenstein, Frankenstein]

So wrote Mary Shelley in her novel; she conceived the story when she was in her teens, wrote it as a short story and later expanded it into a novel with the help of Percy B Shelley. When first published in 1818, her name wasn’t attached to the story—in fact, it was published anonymously. Her name wouldn’t be connected with the narrative until it was translated into French a year later. However, that still didn’t stop people from ascribing the work to her husband! The reader is then left with a question: who was this woman who took Milton’s Paradise Lost and retold it with her own spin, where man is the creator/God who abandons his creation to fend for itself in the wilds of the early nineteenth century?

Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin was the daughter of Mary Wollstonecraft, a feminist and philosopher and William Godwin, a philosopher. They were the most intellectual couple of their time. Mary herself must have inherited much of their fire and drive as well as their sense of perception—she seems to have been a learned intellectual as well. And she took her knowledge and integrated it directly into her story blending folklore, literature and her imagination into a cohesive, timeless narrative.

Her style and voice were unique. One of the interesting ironies of Shelley’s narrative is the overall biblical undertone of her novel, which is most likely due to the strong bond the work shares with Milton—ironic because of the subject matter of the story, the voice of the narrative, and even the progression of the story have no other true connection to the bible.

There are two texts the creature has with him to not only bring comfort during his exile, but to also educate—Milton, and Dr. Frankenstein’s journal. From Milton, he learns about good, evil, and the divine roots of man as a being created by God, therefore entitled to an afterlife in the presence of the supreme deity. He identifies with the rest of mankind as if he shared the same origins as every other man. It is from Dr. Frankenstein’s journal he learns his actual beginnings as a creation of man, not God and how he was pieced together from an assortment of unwanted segments and scraps from cadavers—the dead, the vile of the vilest. At that moment, he realizes he is not like every other man; because of his beginnings he has no soul, no chance of eternal life, and more importantly, he knows from his Milton there will be no admittance into the glories of heaven for him. When he tries to interact with his fellow man, this important point is driven home with even more force. He sees just how different he is, and what an abomination he is by viewing himself through the eyes of others. The creature is alone, unwanted by both man and his creator. His loneliness can not be eased. Through what he perceives as unwarranted (and in the beginning, it is unnecessary) ill treatment, he becomes a wretched being with no hope of redemption for he also loses the faith in God he learns through reading Milton.

There are two texts the creature has with him to not only bring comfort during his exile, but to also educate—Milton, and Dr. Frankenstein’s journal. From Milton, he learns about good, evil, and the divine roots of man as a being created by God, therefore entitled to an afterlife in the presence of the supreme deity. He identifies with the rest of mankind as if he shared the same origins as every other man. It is from Dr. Frankenstein’s journal he learns his actual beginnings as a creation of man, not God and how he was pieced together from an assortment of unwanted segments and scraps from cadavers—the dead, the vile of the vilest. At that moment, he realizes he is not like every other man; because of his beginnings he has no soul, no chance of eternal life, and more importantly, he knows from his Milton there will be no admittance into the glories of heaven for him. When he tries to interact with his fellow man, this important point is driven home with even more force. He sees just how different he is, and what an abomination he is by viewing himself through the eyes of others. The creature is alone, unwanted by both man and his creator. His loneliness can not be eased. Through what he perceives as unwarranted (and in the beginning, it is unnecessary) ill treatment, he becomes a wretched being with no hope of redemption for he also loses the faith in God he learns through reading Milton.

“I was trashed; a mist came over my eyes…but I was quickly restored by the cold gale of the mountains. I perceived, as the shape came nearer, (sight tremendous and abhorred!) that it was the wretch whom I had created.” [Victor Frankenstein, Frankenstein]

The Creature’s final blow comes when his creator, his God, Dr. Frankenstein, rejects him; his anger mimics what Adam must have felt as he was being expelled from the Garden of Eden by his creator; thus identification of the creature with mankind is intensified. Underscoring this alignment is the absence of the word “monster” in the text—nowhere in the narrative does Shelley use that pronoun to describe her character. This also helps the reader to identify with the creature, especially in the passages where we experience the story through the creature’s point of view—as we identify with the creature, we also sympathize with him.

It is in this sympathy that we find the enduring popularity of the story; it was popular even in the author’s lifetime. The novel was published in 1818, and the first staging of the story began shortly after. Interestingly, not all of these performances were plays—some performances were also operas. The earliest operatic performance of Shelley’s story was titled Presumption: or the Fate of Frankenstein premiered in 1823 and was written by R. B. Peake. According to Elizabeth Miller in her article “Dracula and Frankenstein a Tale of Two Monsters,” she credits this specific opera with coining the now iconic phrase; “It lives! It lives!”

It is in this sympathy that we find the enduring popularity of the story; it was popular even in the author’s lifetime. The novel was published in 1818, and the first staging of the story began shortly after. Interestingly, not all of these performances were plays—some performances were also operas. The earliest operatic performance of Shelley’s story was titled Presumption: or the Fate of Frankenstein premiered in 1823 and was written by R. B. Peake. According to Elizabeth Miller in her article “Dracula and Frankenstein a Tale of Two Monsters,” she credits this specific opera with coining the now iconic phrase; “It lives! It lives!”

Miller also notes that Mary Shelley eventually attended a performance of a play “…and commented that she was ‘much amused and it appeared to excite a breathless eagerness in the audience’…” I can only assume that she was one of those audience members! An interesting aside Miller also offers is “A second adaption opened the same year, as did a trio of comedic versions.” My mind reels with the possibilities of what a comedic treatment of Frankenstein would be like in 1823 without Abbot and Costello, the Bowery Boys, and the Three Stooges!

Sources: Frankenstein, or The modern Prometheus by Mary Wollstonecroft Shelley; “Dracula and Frankenstein a Tale of Two Monsters” by Elizabeth Miller; and class notes.