[Posted by Joel Kalodner for ENG 812 Modern Poetry, Professor Rosen]

[Posted by Joel Kalodner for ENG 812 Modern Poetry, Professor Rosen]

“That Darwinian Gosling”

If the wishes of American poet Marianne Moore had been honored, this slim collection of her poetry — her first publication outside the pages of literary magazines and landmark Modernist journals such as Dial and the Egoist — would have remained unmade and unread.

Famously resistant to publication after several early disappointments, and with a well-deserved reputation for perfectionism, Moore had by 1921 weathered several years’ worth of importuning in favor of a collection from friends and admirers including Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, H.D, Yvor Winters and Robert McAlmon. Eliot offered his personal assistance from post-war London, writing to Moore that “[Your poetry] interests me. I wish that you would make a book of it, and I should like to try to get it published here. I wish you would let me try.” Pound, likewise, was enthusiastic and just before Christmas, 1918 wrote to tempt her with a prime spot in his Modernist pantheon: “[C]an I get one into print for you? … I have got Joyce, and Lewis, and Eliot, and a few other comforting people into print, by page and by volume.” More scathing was her friend Yvor Winters’ critique, who, while once again advocating for publication, chided Moore for her reticence: “People who leave poems littered around in the magazines are so very much like people who leave papers around in the parks. But that, I suppose, is their own affair.”

By late 1920, some of her advocates had had enough and together the poet H.D., the historical novelist Bryher (pen name of Winifred Ellerman), and Ellerman’s soon-to-be husband Robert McAlmon agreed to take matters into their own hands. Selecting twenty-four of Moore’s poems from various magazines, the group contacted Harriet Shaw Weaver, then publisher of the Egoist Press in London, with a plan to publish the collection; Weaver was herself intimately familiar with the poet’s position on the topic, having suffering a fresh, albeit polite, rejection after she’d proposed a similar book to Moore as recently as that May. Despite the unusual circumstance, Weaver agreed to go behind the poet’s back and produced the volume without ever securing her approval.

By late 1920, some of her advocates had had enough and together the poet H.D., the historical novelist Bryher (pen name of Winifred Ellerman), and Ellerman’s soon-to-be husband Robert McAlmon agreed to take matters into their own hands. Selecting twenty-four of Moore’s poems from various magazines, the group contacted Harriet Shaw Weaver, then publisher of the Egoist Press in London, with a plan to publish the collection; Weaver was herself intimately familiar with the poet’s position on the topic, having suffering a fresh, albeit polite, rejection after she’d proposed a similar book to Moore as recently as that May. Despite the unusual circumstance, Weaver agreed to go behind the poet’s back and produced the volume without ever securing her approval.

We can imagine Moore’s shock when, one morning in early July of 1921, a similar volume to the Watkinson’s showed up in her mailbox shipped straight from the Egoist Press, London, her name gracing its cover and the very poems she’d so vigorously guarded now printed within. Although she refused to indulge in anger or assign blame, explaining at the time that she knew her friends had acted “out of love,” Moore nonetheless had sharply wry words for Bryher in a letter written that afternoon: “I received a copy of my poems this morning with your letter and a letter from Miss Weaver … In Variations of Plants and Animals under Domestication, Darwin speaks of a variety of pigeon that is born naked and without any down whatever. I feel like that Darwinian gosling.”

A Passion for Revision

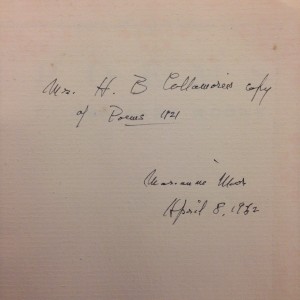

Of particular note in the Watkinson’s copy of Poems (1921) is the presence of hand-written corrections to the text by Marianne Moore herself. This extraordinary habit was apparently characteristic of the poet, who made it her practice to revise, in pen, those things within her previously published volumes which had come to displease her. In the Watkinson’s copy, inscribed by Moore herself to noted bibliophile and Trinity stalwart Harry Bacon Collamore in 1957, we witness the poet carefully editing ‘mistakes’ fixed into print some thirty-six years previous, with a firm hand and a practiced attention to detail: not ‘Talisman’ but rather ‘A Talisman’ she insists, appending the new letter both to the table of contents and the head of the poem, even as she attentively re-works the notices of prior publication to correct what she must have felt were unforgivable failures made during the placement of commas in the original.

Of particular note in the Watkinson’s copy of Poems (1921) is the presence of hand-written corrections to the text by Marianne Moore herself. This extraordinary habit was apparently characteristic of the poet, who made it her practice to revise, in pen, those things within her previously published volumes which had come to displease her. In the Watkinson’s copy, inscribed by Moore herself to noted bibliophile and Trinity stalwart Harry Bacon Collamore in 1957, we witness the poet carefully editing ‘mistakes’ fixed into print some thirty-six years previous, with a firm hand and a practiced attention to detail: not ‘Talisman’ but rather ‘A Talisman’ she insists, appending the new letter both to the table of contents and the head of the poem, even as she attentively re-works the notices of prior publication to correct what she must have felt were unforgivable failures made during the placement of commas in the original.

Grace Schulman, editor of the Penguin Classics collection of Moore’s poetry, recalls the poet sending Schulman a copy of her book Nevertheless “with textual insertions and deletions she had made in ink,” a practice Schulman associates with what she calls Moore’s “passion for revision.” The Watkinson’s copy too bears these marks left behind by Moore’s ceaseless, systematic review of her prior work, and stands as evidence of her dedication to change, her steady refusal to accept notions of fixed textual permanence which often attach to the event of publication.

Gadzooks!

Finally, a note for the typographically inclined — throughout this edition we encounter an unusual type of ligature, which is a term typesetters use for any connection inked between two otherwise distinct letters, such as the joined ‘æ’ still employed at times in modern English. In the Watkinson’s Egoist Press edition of Poems, however, there are ligatures on virtually every page, most often linking adjacent s-t and c-t pairs in a purely decorative fashion; this was a ‘house style’ characteristic of their London typesetter, and which was thought to lend text a certain ‘archaic’ quality, reminiscent for readers of the much more widespread use of such decorative techniques by publishers of the past.

The professional term for such a ligature, that is, a ligature which is purely discretionary and used solely for ornament, is a ‘gadzook’ — a term coined, like the curse word which shares its origin, as a variant of the blasphemous “God’s hooks,” referring to the nails used to attach Christ to the cross (that long-time British favorite, ‘bloody,’ is similarly evolved from the blasphemous “God’s blood!”). While the specific origin of this usage in typography is obscure, the visual reference, along with its nod to archaism, remains perfectly clear.

The professional term for such a ligature, that is, a ligature which is purely discretionary and used solely for ornament, is a ‘gadzook’ — a term coined, like the curse word which shares its origin, as a variant of the blasphemous “God’s hooks,” referring to the nails used to attach Christ to the cross (that long-time British favorite, ‘bloody,’ is similarly evolved from the blasphemous “God’s blood!”). While the specific origin of this usage in typography is obscure, the visual reference, along with its nod to archaism, remains perfectly clear.

Sources:

Schulze, Robin G., ed. Becoming Marianne Moore: The Early Poems, 1907-1924. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002. Print.

Schulman, Grace, ed. The Poems of Marianne Moore. New York: Penguin Books, 2005. Print.

Shin, Nick. “Diggin’ It: The Buried Treasures of Typography.” Graphic Exchange mag. N.d. Web. 21 April 2016.