Auden artifact

[Posted by Sean Flynn for ENG 812 Modern Poetry, Professor Rosen]

Auden artifact unearths interesting connection between poets and their readers.

“That is just what I think is wrong with modern poetry – The poets are not writing for the people, for a vast audience – They are writing for a small clique – And then the members of this small group interpret these poems to the public through books, articles and reviews,” writes former Trinity College Vice President Albert E. Holland.

“That is just what I think is wrong with modern poetry – The poets are not writing for the people, for a vast audience – They are writing for a small clique – And then the members of this small group interpret these poems to the public through books, articles and reviews,” writes former Trinity College Vice President Albert E. Holland.

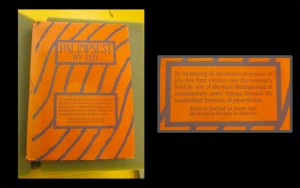

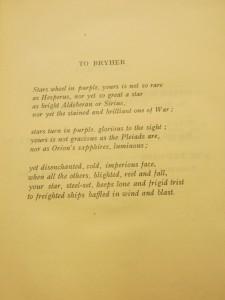

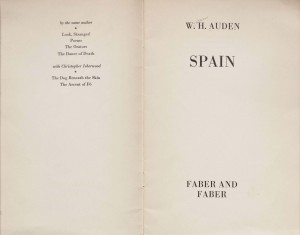

When Albert E. Holland donated an original copy of “Spain” by W.H. Auden to the Trinity College graduating class of 1946, he gave his classmates a clear explanation why. An overview of Holland’s thirteen-year journey between his junior year in 1934 and graduating year in 1946 suggests that Holland interpreted the poem as analogous to his darkest moments as a college dropout.

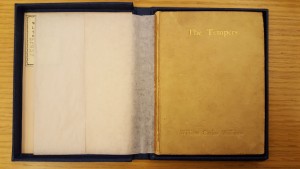

The Watkinson library houses the gift of Holland within a collection of modern poetry artifacts. Along the inside cover of “Spain,” readers find “Gift of Albert E Holland, Class of ’34,” written across the bottom of the page. Dedications like this often transform a large “I found it at the Watkinson” assignment into specific project, more appropriately titled, “I indirectly learned this at the Watkinson.” Brief research on Holland reinforced the fruitfulness of the latter.

In 1933, the Great Depression stole Holland’s senior year at Trinity College. Becoming a workingman prematurely, Holland entered a tanking American economy that summer. But Holland’s fluency in German helped him secure several prestigious positions abroad. In 1937, when W.H. Auden published “Spain,” a poetic treatise on the Spanish Civil war, Holland established himself as the point person for Brown Brothers Harriman office in Berlin. Perhaps Holland, who then stood at the apex of his private sector ascent, did not find value in the poem like he did when donating an original copy to the Trinity class of ‘46.

After working on projects in Germany, Netherlands, and the United States, the North Negros Sugar Company of Manila culled Holland in 1941. Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japan invaded Philippines, where Holland, his wife, and two young children lived. For three years they remained incarcerated at the Santo Tomas internment camp. Holland spent the next thirty-seven months reading and keeping an extensive diary.

In the daily entries, Holland documents air raids and his day-to-day mindset.

“Today Lt. Shiragi said that we should kill all the dogs in the camp & serve them on the food line – I agree that the dogs should be killed – They are a menace to our health – But I do not relish eating these mangy mongrels – This shows while I may be very hungry, I am not yet starving – Otherwise I would make no such objection,” writes Holland.

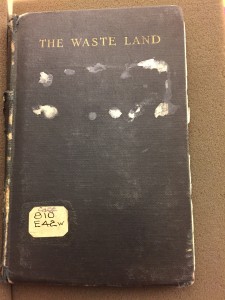

Despite obvious struggles as a prisoner of war, Holland displays a poised and thoughtful demeanor throughout his diaries. He cites a range of books and modern poets who helped him cope, including Auden. “Auden, Spencer, MacNeice, Stevens, E. E. Cummings & – in many poems T. S. Eliot – all apparently disdain us – Look at Eliot’s “Wasteland,” The same is true of Stein, Wolfe & Joyce in the novel – It is never necessary to be incomprehensible – And I detest poems composed of words put down for their musical effect & not for their meaning,” writes Holland.

While Holland criticized modern poets that wrote “incomprehensible” lines, Holland certainly viewed Auden’s “Spain” as comprehensible. When the Japanese internment camp released Holland and his family in 1945, Trinity let Holland walk with the class of 1946. His first donation to Trinity was a copy of Auden’s Spain. Since Auden wrote the poem about the Spanish Civil War, while addressing the grave byproducts of war, perhaps Holland drew many parallels between the poem and his own experience as a POW.

Trinity hired Holland as a freshmen advisor in 1946. He transitioned into various fundraising positions and later became vice president at the college. In 1966, Hobart and William Smith named Holland president, but the school forced his resignation two years later. Fittingly Holland’s early exit stems from an allegiance with Reverand Daniel Berrigan-a Vietnam war activist Holland invited to speak on campus. He finished his career at Wellesley College and retired from higher education in 1977.

That Holland lived to tell his story is nothing short of a minor miracle. The Watkinson library assignment unearthed his seldom-shared story. Yet when Holland dedicated a poem on war and struggle to Trinity, the former administrator told his classmates something else.

Holland lived a reader’s life.

The Auden poem and a typed replication of Holland’s prison diaries can be found at the Watkinson Library.