[Posted by Michelle Murphy ’14, for Prof. David Rosen’s course, “Modern Poetry”]

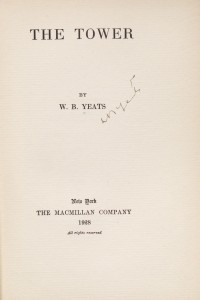

What I found at the Watkinson was the book of poems The Tower by W.B. Yeats that was published in 1928. The book itself is a fascinating and intriguing part of history. The outside paper fold that encompasses the hard-cover book is a forest green with gold-like writing, and slightly torn edges. The paper of the book also caught my attention. It is a thicker material, with a rough texture that suggests it was specifically chosen. The pages are slightly yellow with worn edges. However, the original version may have had irregular edges. It is hard to tell whether or not this is due to aging or whether it is simply the type of paper that was chosen for a specific effect. Either way, it set a different tone for reading these poems. I had to handle each page with care, and frankly liked touching the paper (although I did refrain from excess touching to preserve the book!). The text on the pages was quite a change from the common font size 10 in cheaper paper-backs – the text was perhaps a font size 14-16 with about 2 inch margins surrounding the thick letters, which to my pleasure reminded me of a children’s story (and smiling I said to myself ‘Oh I would love to read a W.B. Yeats’ children’s book!’).

What I found at the Watkinson was the book of poems The Tower by W.B. Yeats that was published in 1928. The book itself is a fascinating and intriguing part of history. The outside paper fold that encompasses the hard-cover book is a forest green with gold-like writing, and slightly torn edges. The paper of the book also caught my attention. It is a thicker material, with a rough texture that suggests it was specifically chosen. The pages are slightly yellow with worn edges. However, the original version may have had irregular edges. It is hard to tell whether or not this is due to aging or whether it is simply the type of paper that was chosen for a specific effect. Either way, it set a different tone for reading these poems. I had to handle each page with care, and frankly liked touching the paper (although I did refrain from excess touching to preserve the book!). The text on the pages was quite a change from the common font size 10 in cheaper paper-backs – the text was perhaps a font size 14-16 with about 2 inch margins surrounding the thick letters, which to my pleasure reminded me of a children’s story (and smiling I said to myself ‘Oh I would love to read a W.B. Yeats’ children’s book!’).

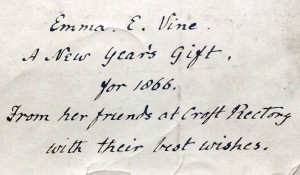

Opening the book and looking at the cover page, there in delicately pressed pencil, was Yeats’ signature, (which was confirmed to be legitimate). Looking at the signature, I wondered if he had always had the same style of if he changed his signature to just his initials and last name in order to better suite his life as a poet.

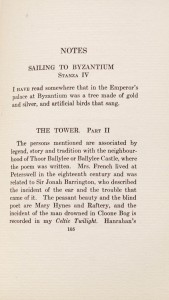

In the back of the book were ‘Notes’ which Yeats added to give a small insight into some of his poems.

I found his notes on the poem ‘Sailing to Byzantium’ to be particularly humorous. Specifically regarding stanza IV: “I have read somewhere that in the Emperor’s palace at Byzantium was a tree made of gold and silver, and artificial birds that sang” (105). After reading this, I chuckled – of all the notes he could have given the reader about this poem, he chose to say this. It is such a simple and matter of fact statement that at first it offers little. However, I considered this: Yeats is a man who hears about small snippets of marvelous things and incorporates them into his poems – or better, into the world he creates in his poems.

I found his notes on the poem ‘Sailing to Byzantium’ to be particularly humorous. Specifically regarding stanza IV: “I have read somewhere that in the Emperor’s palace at Byzantium was a tree made of gold and silver, and artificial birds that sang” (105). After reading this, I chuckled – of all the notes he could have given the reader about this poem, he chose to say this. It is such a simple and matter of fact statement that at first it offers little. However, I considered this: Yeats is a man who hears about small snippets of marvelous things and incorporates them into his poems – or better, into the world he creates in his poems.

For his poem ‘The Tower’ he provides more notes. In the poem, he talks a great deal about certain characters, and here he expands on who these people are – showing that these people are 3-D in his mind and that he puts immense amounts of thought into his poems. Sometimes when I read poetry, even when I read some of Yeats, I become a bit skeptical: that as I am trying to find meaning in the poem, the joke is really on me – the author merely created the illusion of hidden meaning (perhaps that is also an art form?) But reading these notes gives me a sense of security that Yeats had a vision and a true back story for his poems: “The persons mentioned are associated by legend, story and tradition with the neighbourhood of Thoor Ballyllee or Ballylee Castle, where the poem was written” (105). I only wish he could have drawn a picture of this location, but alas the poem with suffice.

His notes on ‘The Tower’ continue about part III. Here he writes: “When I wrote the lines about Plato and Plotinus I forgot that it is something in our own eyes that makes us see them as all transcendence” (107). The lines he is referring to are: “And I declare my faith: / I mock Plotinus’ thought / And cry in Plato’s teeth,/” with the only other reference to them made in stanza I: “It seems that I must bid the Muse go pack, / Choose Plato and Plotinus for a friend/”. Here Yeats points out our tendencies to exalt people such as Plato and Plotinus and goes on to quote Plotinus to leave the reader no doubt that he is not ignorant of those philosophies. Clearly the philosophies of Plato and Plotinus were very important to him and influenced his thoughts (and thus his poems). The last part of the quote from Plotinus reads: “but soul, since it never can abandon itself, is of eternal being’ (107). This note offers insight into Yeats’ life views, and when kept in mind, relate to many of the works that I am familiar with.

His notes on ‘The Tower’ continue about part III. Here he writes: “When I wrote the lines about Plato and Plotinus I forgot that it is something in our own eyes that makes us see them as all transcendence” (107). The lines he is referring to are: “And I declare my faith: / I mock Plotinus’ thought / And cry in Plato’s teeth,/” with the only other reference to them made in stanza I: “It seems that I must bid the Muse go pack, / Choose Plato and Plotinus for a friend/”. Here Yeats points out our tendencies to exalt people such as Plato and Plotinus and goes on to quote Plotinus to leave the reader no doubt that he is not ignorant of those philosophies. Clearly the philosophies of Plato and Plotinus were very important to him and influenced his thoughts (and thus his poems). The last part of the quote from Plotinus reads: “but soul, since it never can abandon itself, is of eternal being’ (107). This note offers insight into Yeats’ life views, and when kept in mind, relate to many of the works that I am familiar with.

Holding this old book, looking at the large letters (flipping back to view his signature between poems) and reading the notes gave me a whole new experience with these poems, and for that, I am thankful that I found it at the Watkinson.

Holding this old book, looking at the large letters (flipping back to view his signature between poems) and reading the notes gave me a whole new experience with these poems, and for that, I am thankful that I found it at the Watkinson.