[Posted by Francis Russo (’13), for Jonathan Elukin’s History of the Book course]

When we first went down into the Watkinson stacks I came up with a gigantic, vellum bound volume filled with pages printed side by side in both Greek and Latin. The massive book was Plutarch’s Life of Alexander—at least, that’s what I could decipher at first glance before I ended up abandoning the monstrosity. In connection with another project, my attention was drawn to another volume quite the opposite of the Alexander text. This new book was small and plain. The spine was no thicker than an index finger and the cover lacked any elaborate design. The simply stamped title, however, was intriguing: Memoirs of Musick. Is this a story of a musical experience, or an autobiography of a musician? Perhaps it’s a history of music or tract on music theory…

When we first went down into the Watkinson stacks I came up with a gigantic, vellum bound volume filled with pages printed side by side in both Greek and Latin. The massive book was Plutarch’s Life of Alexander—at least, that’s what I could decipher at first glance before I ended up abandoning the monstrosity. In connection with another project, my attention was drawn to another volume quite the opposite of the Alexander text. This new book was small and plain. The spine was no thicker than an index finger and the cover lacked any elaborate design. The simply stamped title, however, was intriguing: Memoirs of Musick. Is this a story of a musical experience, or an autobiography of a musician? Perhaps it’s a history of music or tract on music theory…

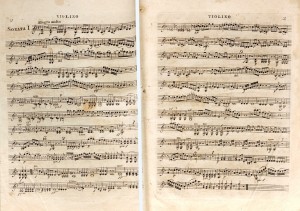

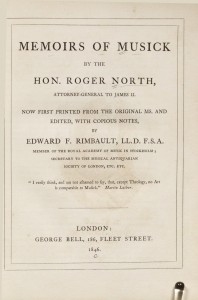

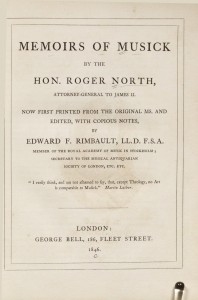

I hoped to find an answer in the title page, but that only added a whole new dimension to the mystery with each line: Memoirs of Musick … by the … Hon. Roger North … Attorney-General to James II … Now first printed from the original MS. and edited, with copious notes … by Edward F. Rimbault, LL.D. F.S.A. … Member of the Royal Academy of Music in Stockholm; Secretary to the Musical Antiquarian Society of London, Etc. Etc. … London … 1846.

Why did a former Attorney-General to James II (the one gently booted off the throne in the Glorious Revolution of 1688) write a piece on Music? And what did a Member of the Royal Academy of Music find in it over a hundred years later that warranted the trouble of editing and printing it?

Before things get too confusing the book explains itself and tells its own history in a short preface. This three-page introduction is a wonderfully detailed tale of the life of North’s original manuscript. It claims that the Memoires of Musick was “first made known to the world” when selections of it appeared in a certain Dr. Burney’s General History of Music. Charles Burney, who received honorary degrees in Music from Oxford in 1769, was an early music historian intent on writing a general history of music and drew on many sources to complete it. After this initial appearance with Burney in the 1770’s, North’s manuscript was bought, sold, inherited and passed down through the hands of more than five people and over a hundred years, having a “very narrow escape from destruction” before finally reaching the “present editor.” The preface also tells us about the book’s contents. The volume is formed from half of North’s original manuscript, a 1728 “sketch of the progress of the art [of music].” It leaves out its counterpart, a “treatise on the Science of Musick.”

After putting the book into some kind of context, two general strands of thought emerge. One is North and his writings about Music and the other is Rimbault’s heavy editorial hand. North is first described in a biographical note as an amateur lover of music, noteworthy for his knowledge on a subject not usually associated with his background of law and politics. North’s writing covers all sorts of musical topics from performance, theory, philosophy and more, reaching back as far back as Ancient Greece. He organizes the work without chapters or any subject headings and seems to ramble on whatever subject amuses him. However, North is aware of his scattered nature and admits at the beginning that he is “not pretending to a full History, a work for Herculean shoulders, but only to collect and modify some Historico-critical scraps.”

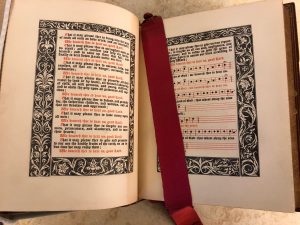

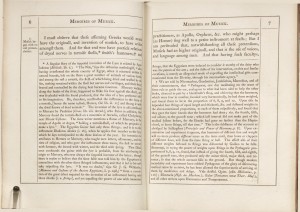

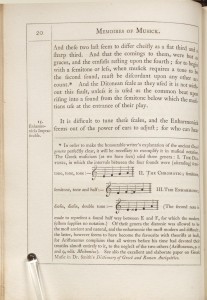

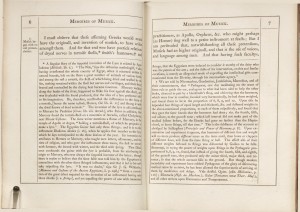

Interestingly, Rimbault is also aware of his own work: “The notes which have been added are the result of much reading, and the peculiar facilities which the editor enjoys of consulting rare works. If their minuteness be sometimes uncalled for in explanation of the text, the new and curious information they convey will, it is hoped, be some excuse for the insertion. [signed] E.F.R.” The reason for this apology in advance becomes abundantly clear once you page through the text. Rimbault formats each page as a grid with separated spaces for North’s text, annotative commentary, decorations, a title heading, pagination, and subject markers in the margins. The commentary is truly overwhelming at many points, to the extent that some pages contain only four or five lines of North’s text and the rest filled with Rimbault’s annotations. It seems Rimbault takes up the “Herculean” task North sought to avoid.

Interestingly, Rimbault is also aware of his own work: “The notes which have been added are the result of much reading, and the peculiar facilities which the editor enjoys of consulting rare works. If their minuteness be sometimes uncalled for in explanation of the text, the new and curious information they convey will, it is hoped, be some excuse for the insertion. [signed] E.F.R.” The reason for this apology in advance becomes abundantly clear once you page through the text. Rimbault formats each page as a grid with separated spaces for North’s text, annotative commentary, decorations, a title heading, pagination, and subject markers in the margins. The commentary is truly overwhelming at many points, to the extent that some pages contain only four or five lines of North’s text and the rest filled with Rimbault’s annotations. It seems Rimbault takes up the “Herculean” task North sought to avoid.

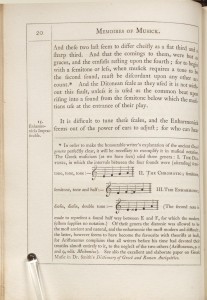

North’s original reference to Hercules brings us to another characteristic of the work. Both North’s text and Rimbault’s commentary are filled with references to the Classical world. What is most interesting is that the book goes to great length describing the music of Ancient Greece and considers Classical myth as well as scholarship as explanations for musical concepts. Discussing the origin of scales, North mentions an “Orphean Harp,” which Rimbault picks up on: “according to several traditions preserved by Greek historians, it was Orpheus who completed the second tetrachord, which extended the scale to a heptachord, or seven sounds. The assertion of many writers that Orpheus added two new strings to the lyre, which before had seven, clashes with the claims of Pythagoras to the invention of the octachord…” Rimbault’s dense discussion goes on for much longer, in this case and throughout the entire book. It would be fascinating to find the other half of North’s manuscript and see what he considers to be the “Science of Music.” Do the physics-based principles of harmony and sound we know today come out in North’s explanation?

Rimbault’s extensive and thick commentary also brings out another color of the book. It seems that Rimbault’s printing of such a fragmentary and unknown work is more of a scholarly project than anything else. His interest is to explain and organize the work in a way suggesting that contemporary audiences would not be able to understand North’s 100+ year old original if it were not for him. In this sense, the book also becomes an effort in historical preservation.

Rimbault’s extensive and thick commentary also brings out another color of the book. It seems that Rimbault’s printing of such a fragmentary and unknown work is more of a scholarly project than anything else. His interest is to explain and organize the work in a way suggesting that contemporary audiences would not be able to understand North’s 100+ year old original if it were not for him. In this sense, the book also becomes an effort in historical preservation.

I will end this brief overview of this truly fascinating and multi-faceted book with an anecdote North provides. Although much of his discussion is technical, sometimes confusing, and I suspect in many cases inaccurate, he does sometimes speak to a certain universally. When posing the question of why perfectly good contemporary music was forgotten, “laid aside” and even “contemned,” North says that “This would be harder to answer, if it were not a great truth, and notorious, that every age since Apollo did not say the same thing of the musick of their owne time. For nothing is more a fashion then musick.”

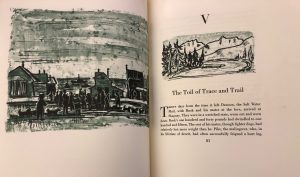

Back when I was in elementary or early middle school, there was a period of a few months when everyone was reading Jack London novels like White Fang or The Call of the Wild. Something about those tales of struggle in the wilderness appealed to our suburban sensibilities. So, when I found this specially bound edition of The Call of the Wild in the Watkinson’s Private Press collection this summer, I was naturally excited. In 1960, the book (originally published in 1903) was reprinted for the members of the Limited Editions Club, who clearly had a flair for the aesthetic. The Yukon adventure novel has been bound in wool and died in a green and black plaid pattern–an appropriately outdoorsy choice. In addition, beautiful illustrations have been added that really capture the mood of the story. I like this edition because it shows how form and content can be made to harmonize. It also reminds me that even books that are not considered high literature can still be special.

Back when I was in elementary or early middle school, there was a period of a few months when everyone was reading Jack London novels like White Fang or The Call of the Wild. Something about those tales of struggle in the wilderness appealed to our suburban sensibilities. So, when I found this specially bound edition of The Call of the Wild in the Watkinson’s Private Press collection this summer, I was naturally excited. In 1960, the book (originally published in 1903) was reprinted for the members of the Limited Editions Club, who clearly had a flair for the aesthetic. The Yukon adventure novel has been bound in wool and died in a green and black plaid pattern–an appropriately outdoorsy choice. In addition, beautiful illustrations have been added that really capture the mood of the story. I like this edition because it shows how form and content can be made to harmonize. It also reminds me that even books that are not considered high literature can still be special.