An American Fairy Tale

[Posted by Jackie Pennell (’14) a student in Zak Sitter’s English course, “1816: A Romantic Microcosm”]

When I was looking over the very long list of publications from the year 1816, I was unsure of what book to study. I decided that Crystalina, A Fairy Tale seemed an interesting choice because I have always enjoyed fairytale stories. When I went to the Watkinson to examine the book, I was not sure of what to expect. I was handed a large book binding that contained an envelope with the actual book inside.

When I was looking over the very long list of publications from the year 1816, I was unsure of what book to study. I decided that Crystalina, A Fairy Tale seemed an interesting choice because I have always enjoyed fairytale stories. When I went to the Watkinson to examine the book, I was not sure of what to expect. I was handed a large book binding that contained an envelope with the actual book inside.

Crystalina has a blue, cardboard binding which is as worn as its pages. I found it in a larger envelope because the front cover of the book is completely detached. Upon inspecting the pages of the book, Rick Ring informed me that the book is comprised of full and half sheets of paper. The half sheets indicate that Crystalina was not as expensive to print as a book printed entirely on full sheets of paper.

When I was examining the cover page, I discovered that Crystalina, A Fairy tale by an American, was published in New York by George F. Hopkins in 1816. I was surprised that the author of Crystalina, John Milton Harney, is not mentioned on the cover page. All that is mentioned about Harney on the title page is that he is American. The preface of the narrative poem also mentions that John Milton Harney is a “native of the United States”.

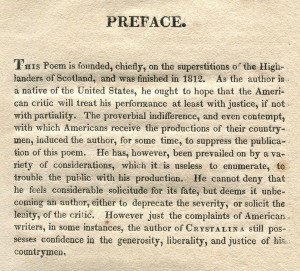

The preface is interesting because it informs the reader of the origins of the poem along with Harney’s apprehension in publishing Crystalina. It is written in third person, so it is unclear whether Harney wrote it himself. However, the reader may infer that Harney wrote the preface because it reveals his concerns that the American critic will receive his work with “proverbial indifference and even contempt”. The reader learns that Harney completed Crystalina in 1812, but decided not to publish the poem until 1816. From reading the preface, it is clear that the uncertainty Harney feels in publishing Crystalina might be the reason why he is not specifically mentioned as the author in the published book. Harney finally published the poem placing faith in the “generosity, liberality, and justice of (Harney’s) fellow countrymen” that they might receive the poem well.

The preface is interesting because it informs the reader of the origins of the poem along with Harney’s apprehension in publishing Crystalina. It is written in third person, so it is unclear whether Harney wrote it himself. However, the reader may infer that Harney wrote the preface because it reveals his concerns that the American critic will receive his work with “proverbial indifference and even contempt”. The reader learns that Harney completed Crystalina in 1812, but decided not to publish the poem until 1816. From reading the preface, it is clear that the uncertainty Harney feels in publishing Crystalina might be the reason why he is not specifically mentioned as the author in the published book. Harney finally published the poem placing faith in the “generosity, liberality, and justice of (Harney’s) fellow countrymen” that they might receive the poem well.

The poem consists of six Cantos and as the preface states, it is “founded chiefly, on the superstitions of the highlanders of Scotland”. The plot of the poem is typical of a classic fairy tale story. The hero of the story is a gallant knight named Rinaldo who must prove himself worthy to marry the princess Crystalina. When Rinaldo proves himself worthy by fighting in battle, he returns to find Crystalina gone. In the first canto, Rinaldo ventures to find a seer who reveals that Crystalina has been abducted. The rest of the poem follows Rinaldo on his quest to find and save Crystalina.

Crystalina is organized into lengthy stanzas and it is in iambic pentameter. The first stanza of the poem has a rhyme scheme of ABAB, but the rest of the first canto has an AABBCC…rhyme scheme. The literary style of the first canto reminds me slightly of Milton’s epic poetry. Like much of Milton’s poetry, there are several references to mythological figures such as Orestes, and Rinaldo compares himself to Tantalus. There is also dialogue within the poem such as in the first canto when there is dialogue between the seer and Rinaldo.

After the six cantos, there is a separate short poem entitled “The Ecstacy”. The poem has three shorter stanzas; in the first stanza, the speaker of the poem is imploring nature to prevent disaster and hardship. In the second and third stanzas, the speaker asks nature to bring joy and happiness. The final short poem “The Ecstacy” is certainly a fitting ending for Harney’s happily-ever-after fairytale.