Shall We Dance?

[Posted by Amanda Daddona, a graduate student in American Studies at Trinity, for AMST 838: America Collects Itself: From Colony to Empire]

A Dancing Companion: Thomas Hillgrove’s Practical Guide to Social Dance in America

A Dancing Companion: Thomas Hillgrove’s Practical Guide to Social Dance in America

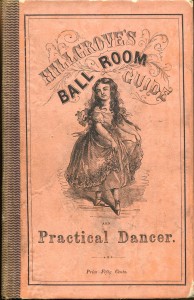

Tucked away in the stacks of the Watkinson is a small dance manual bound in powder-pink boards, the front of which is beautifully illustrated with the image of a young woman with loose, flowing hair in a voluminous dress and delicate ribboned shoes. The decorative script on the front cover bears the title: Hillgrove’s Ball Room Guide and Practical Dancer. The manual, written by the dance instructor Thomas Hillgrove, was first published in New York in 1863, though this particular version was printed in 1864, with another to follow in 1869. The primary purpose of the book, according to Hillgrove’s note in the beginning pages, was to offer uniform instruction in the proper execution of dances, and to promote general interest and enjoyment of dancing.

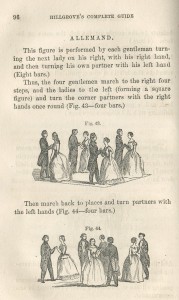

The book opens with a more detailed summary of the material covered: “A Complete Practical Guide to the Art of Dancing, Containing Descriptions of All Fashionable and Approved Dances, Full Directions for Calling the Figures, the Amount of Music Required, Hints on Etiquette, the Toilet, Etc.” The manual is divided into six parts, each of which begins with a detailed illustration of men and women in full ball dress. In general, the majority of the book is illustrated with figures—either representations of men and women, or x’s and o’s—to facilitate the reader’s visualization and comprehension of each dance step. The six parts cover a range of material, from proper dress and etiquette in the ballroom, to instructions for execution of steps, to proper procedures for planning balls and private dances.

The first part of the book is devoted to proper dress, deportment, and etiquette. According to Hillgrove, a woman should wear colors that are complimentary to her complexion, and dresses should be an appropriate length to avoid tripping on hems. He also recommends wearing only a simple flower in the hair, if a lady should choose to adorn her head. Introductions are not necessary unless the couple believes they will meet again outside of the ball room, in which case gentlemen are always introduced to ladies, and younger people are introduced to their elders, and not the other way around in either instance. Other instructions regarding ball room etiquette contain a hint of humor; in particular, Hillgrove warns that “the practice of chewing tobacco and spitting on the floor, is not only nauseous to ladies, but is injurious to their dresses,” and for the more clumsy dancers, “if you cannot waltz gracefully, do not attempt to waltz at all.” The first part ends with a discussion of ballroom shape, type of floor, and music, as well as a description of proper etiquette for the supper room.

The second part addresses rudiments of dancing, such as positioning of the head, chest, arms, back, and legs, as well as how and when to bow and courtesy to a partner. Hillgrove considers the bow and courtesy to be “the most important rudiments of juvenile education; a proper knowledge of them being indispensable,” and so describes the method for men and women to greet one another, not just on the dance floor, but in passing, as well. In general, Hillgrove states that there should be harmony at all times when dancing, among all parts of the body. In regard to the position of the feet, Hillgrove provides several illustrations of proper placement, which are—quite interestingly—very similar to the first through fifth positions of the feet in ballet. The chapter ends with a discussion of strengthening exercises that are also practiced in ballet: plies and battements.

The second part addresses rudiments of dancing, such as positioning of the head, chest, arms, back, and legs, as well as how and when to bow and courtesy to a partner. Hillgrove considers the bow and courtesy to be “the most important rudiments of juvenile education; a proper knowledge of them being indispensable,” and so describes the method for men and women to greet one another, not just on the dance floor, but in passing, as well. In general, Hillgrove states that there should be harmony at all times when dancing, among all parts of the body. In regard to the position of the feet, Hillgrove provides several illustrations of proper placement, which are—quite interestingly—very similar to the first through fifth positions of the feet in ballet. The chapter ends with a discussion of strengthening exercises that are also practiced in ballet: plies and battements.

The following four segments of the book are devoted to instruction on figures, or steps, in all the major dances of the time, the most popular of which was the quadrille. Hillgrove speculates that the quadrille was so popular because it was a social dance that allowed for conversation, as well as frequent changing of partners. The dance consisted of five parts and was danced by sets of four women and four gentlemen who all had appointed places within their set. As it was the most widely performed dance, there were many variations, which Hillgrove describes in detail. In addition to the illustrated instructions on how to execute the figures, Hillgrove also made note of musical cues that dancers should follow in order to properly perform the dances.

After the lengthy segment on the quadrille and all of its variations, Hillgrove moves on to the waltz. He begins with an assessment of a good waltz dancer, who should always keep good posture, handle his or her partner with ease and grace, avoid colliding with other couples on the floor, and “dance naturally and with no artificiality.” As the waltz and other “round dances” were performed with only one partner, Hillgrove described the proper hand placement for both the gentleman and the lady, and encouraged dancers to maintain an appropriate amount of space between them. The book continues with a description of waltz variations, such as La Czarine, the Russian Waltz, and the Hop Waltz, and provides some background and historical information on where and how the variations began. He continues with the polka and other international dances, and ends the fifth segment with a rather disparaging commentary on country dances, which were then considered “rude” and “inferior in the light of modern dancing.” Country dances, in Hillgrove’s opinion, were wild and raucous.

The book concludes with Hillgrove’s observations regarding proper arrangement for musical instruments. For example, if only one instrument is needed, it should be a violin. If not a violin, it should be a pianoforte. If two instruments are needed, the most desirable combination was a violin and pianoforte; if that could not be arranged, then a harp and violin, or a violin and violincello. He continues this list until the number of instruments is quite large, and says that he has surmised these are the best instrument combinations based on the reaction of people at balls and soirees. Hillgrove also discusses the proper procedure for hosting a dance or soiree, which includes hiring a room, musicians, and doorkeepers, as well as making arrangements for advertisements, ticket sales, invitations, and proper maintenance of all expenditures and receipts.

Thomas Hillgrove’s Practical Guide to the Art of Dancing provides the modern reader with a glimpse into the very structured world of ballroom dance, and also gives an indication of the prevalence and importance of dance in society. It is an informative, beautifully illustrated, and incredibly entertaining book that has been useful for several researchers working on dance history. This manual, and others like them, are not only fun to read, but they also provide scholars with a way to delve more deeply into the beginnings of social dancing in America.