How to Bring Up Baby

Though raising children will never go out of style, certain fads, methods, or ideas will surely change in the years to come and have definitely changed over the years. Elizabeth Robinson Scovil published her book How to Raise a Baby in 1906, and I was actually surprised to find her methods were not completely off-the-wall or out-of-date. This may be because Scovil was actually a graduate of the Massachusetts General Hospital Training School for Nurses, so it is safe to say that she was well educated and a source that women would have trusted. She was also the author of a number of other texts, including: “A Baby’s Requirements,” “The Care of Children,” and “Preparation for Motherhood.” Her writing did not stop at simple advice on how to be a mother, and she also wrote other books on how to be a proper girl and woman. One of her other texts was “Prayers for Girls,” published in 1924, and “Little Prayers for Little Lips,” published in 1921.

Though raising children will never go out of style, certain fads, methods, or ideas will surely change in the years to come and have definitely changed over the years. Elizabeth Robinson Scovil published her book How to Raise a Baby in 1906, and I was actually surprised to find her methods were not completely off-the-wall or out-of-date. This may be because Scovil was actually a graduate of the Massachusetts General Hospital Training School for Nurses, so it is safe to say that she was well educated and a source that women would have trusted. She was also the author of a number of other texts, including: “A Baby’s Requirements,” “The Care of Children,” and “Preparation for Motherhood.” Her writing did not stop at simple advice on how to be a mother, and she also wrote other books on how to be a proper girl and woman. One of her other texts was “Prayers for Girls,” published in 1924, and “Little Prayers for Little Lips,” published in 1921.

Interestingly, How to Bring Up a Baby was provided as a complimentary gift for women along with their Ivory Soap purchases, which explains why the publisher of her text is Procter and Gamble, the popular American consumer goods company. Procter and Gamble insert promotions for their product throughout the booklet. For instance: “No soap but a pure scentless one like Ivory Soap” should be used” (25) or “Children will brush their teeth if they have a tooth wash that tastes nice. There is none better than half an ounce of Ivory Soap (one-twelfth of a small cake) dissolved in four ounces of water with a teaspoonful of rose water as flavoring” (35-36). These examples are not uncommon throughout Scovil’s text.

Interestingly, How to Bring Up a Baby was provided as a complimentary gift for women along with their Ivory Soap purchases, which explains why the publisher of her text is Procter and Gamble, the popular American consumer goods company. Procter and Gamble insert promotions for their product throughout the booklet. For instance: “No soap but a pure scentless one like Ivory Soap” should be used” (25) or “Children will brush their teeth if they have a tooth wash that tastes nice. There is none better than half an ounce of Ivory Soap (one-twelfth of a small cake) dissolved in four ounces of water with a teaspoonful of rose water as flavoring” (35-36). These examples are not uncommon throughout Scovil’s text.

I unfortunately could not find an image of the particular Ivory Soap product that this booklet was accompanied by; it may have been a variety of products. Instead, I looked into what types of advertisements Ivory Soap had out in 1906. Those, too, unsurprisingly, were directed toward women. Two such ads are included on the previous page. These ads fit into the same vein as the messages within Scovil’s text.

Scovil’s books are still available online and do not run for very high prices. They are available from sources like Amazon and AbeBooks. There are various editions of How to Bring Up a Baby listed, ranging in price from $10 to $40. Our Watkinson copy seems to be in better shape than some of the others listed, as its pages are made of some sort of silky, smooth cardboard, and there are no pages missing. There are forty pages in this text, and colored illustrations are included (and dispersed throughout this blog post). Our particular copy appears to have been a gift from the Grom Hayes Library in Hartford, as recorded on the inside cover of the book.

Scovil’s books are still available online and do not run for very high prices. They are available from sources like Amazon and AbeBooks. There are various editions of How to Bring Up a Baby listed, ranging in price from $10 to $40. Our Watkinson copy seems to be in better shape than some of the others listed, as its pages are made of some sort of silky, smooth cardboard, and there are no pages missing. There are forty pages in this text, and colored illustrations are included (and dispersed throughout this blog post). Our particular copy appears to have been a gift from the Grom Hayes Library in Hartford, as recorded on the inside cover of the book.

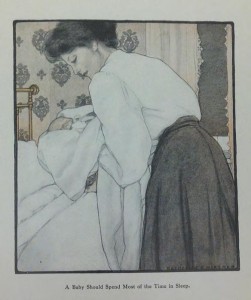

There is no table of contents for the text, but the first page of the booklet is worth noting. In order to be able to personalize her copy of the book, a woman could fill in her baby’s specific details on the first page, as shown on the right. I imagine this was amusing for women reading the book, knowing they could apply the reading material to their own child. In that way, they could know if they were correctly “bringing up a baby.” They could also compare their children’s statistics to what was considered to be average in the day. If their babies fell within normal limits, they could rest assured; if not, they could read on and figure out where they, as mothers, went astray and how to address the problem. This book puts a lot of pressure on the mothers.

After this opening page, Scovil provides what could only be considered threatening advice. For instance, Scovil says, “Success in life depends largely on the care that is taken of the health in childhood” (7), and “A child has the right to ask that his parents shall give him a fair start; that they shall not allow him to contract disabilities that could have been avoided by careful oversight” (7). She also mentions that there is too high a “Number of children who die annually from entirely different causes” (7). These causes, she maintains, are preventable with expert care. In fact, she states, “Incessant and intelligent care is necessary to overcome the tendency to disease, and to enable them to become strong” (7).

After this opening page, Scovil provides what could only be considered threatening advice. For instance, Scovil says, “Success in life depends largely on the care that is taken of the health in childhood” (7), and “A child has the right to ask that his parents shall give him a fair start; that they shall not allow him to contract disabilities that could have been avoided by careful oversight” (7). She also mentions that there is too high a “Number of children who die annually from entirely different causes” (7). These causes, she maintains, are preventable with expert care. In fact, she states, “Incessant and intelligent care is necessary to overcome the tendency to disease, and to enable them to become strong” (7).

After the first page personalization and her brief note that includes the many threats and warnings, Scovil goes on to write her book about effective childcare. (I use the word “book” lightly because I might consider this more an instructional pamphlet, booklet, or manual than a book.) She divides her book into the following sections: “When to be alarmed,” “Office of the physician,” “Food,” “Sleep,” “Dress,” “Cleanliness,” “Removing stains,” “Ventilation,” “The eyes,” “The ears,” “The nose,” “The teeth,” “The hair,” “The nails,” “Emergencies,” and “Poisoning.” These sections provide pretty solid information, nothing too drastic, but what interested me the most was what Scovil decided to emphasize (with italics) in each passage. Below, I will insert the seven passages from the book she puts particular emphasis on:

After the first page personalization and her brief note that includes the many threats and warnings, Scovil goes on to write her book about effective childcare. (I use the word “book” lightly because I might consider this more an instructional pamphlet, booklet, or manual than a book.) She divides her book into the following sections: “When to be alarmed,” “Office of the physician,” “Food,” “Sleep,” “Dress,” “Cleanliness,” “Removing stains,” “Ventilation,” “The eyes,” “The ears,” “The nose,” “The teeth,” “The hair,” “The nails,” “Emergencies,” and “Poisoning.” These sections provide pretty solid information, nothing too drastic, but what interested me the most was what Scovil decided to emphasize (with italics) in each passage. Below, I will insert the seven passages from the book she puts particular emphasis on:

“Whenever it should be, and no oftener, Ivory Soap is mentioned; and, invariably, a reason for its use is given” (3). “No oftener?” I’m not so sure about that… Ivory Soap is mentioned 18 times so on average, every other page. This proves the text is intended to be a promotional piece for Ivory Soap.

“It may not be out of place, to add that for nearly thirty years, Ivory Soap has enjoyed a unique position in the homes of the majority of intelligent Americans. For bath, toilet, and fine laundry purposes, it has no equal” (4). “Intelligent Americans?” Was this supposed to compliment her readers and make them feel good about themselves? Was this an elitist brand of soap? Is that why she mentions that Ivory Soap is to be used for “fine laundry” purposes? What would be the opposite of “fine laundry,” I wonder?

“It may not be out of place, to add that for nearly thirty years, Ivory Soap has enjoyed a unique position in the homes of the majority of intelligent Americans. For bath, toilet, and fine laundry purposes, it has no equal” (4). “Intelligent Americans?” Was this supposed to compliment her readers and make them feel good about themselves? Was this an elitist brand of soap? Is that why she mentions that Ivory Soap is to be used for “fine laundry” purposes? What would be the opposite of “fine laundry,” I wonder?

Scovil mentions that children need nourishing food for their school lunches and may have “a piece of cake but no pastry” (18). Heaven forbid that a child would eat a pastry! She doesn’t elaborate on this advice as the merits of cake versus pastry, but she does allow the children a slice of cake.

“The most exquisite cleanliness is necessary in the care of bottles and everything used in the preparation of the food. The baby’s life depends on this” (15). This emphasis reminds me of the first page. Scovil makes clear the very high stakes involved in raising a child and how essential Ivory Soap is to that undertaking.

When speaking of wet weather, Scovil advises that, “The feet should be well shod in thick boots and rubbers. Rubber boots may be worn if circumstances permit of their being removed” (22). I really can’t explain her emphasis here. Aren’t shoes always removed eventually?

When speaking of wet weather, Scovil advises that, “The feet should be well shod in thick boots and rubbers. Rubber boots may be worn if circumstances permit of their being removed” (22). I really can’t explain her emphasis here. Aren’t shoes always removed eventually?

“Never box a child’s ears” (33). This makes sense; do not physically abuse your child (obviously). I don’t know if the emphasis was because this was a common problem at the time, or if this was something she considered to be highly detrimental to the proper growth of children. Both seem like good reasons to me.

“When a child swallows any small body, as a pin, or a cent, give soft food—potatoes, oatmeal, or bread and milk. Use no medicine. The substance will probably become imbedded in the soft mass and pass safely away” (39). Here, I think Scovil assumes that mothers will panic and quickly resort to any type of stomach medicine available. She further advises that, if the object does not naturally remove itself from the child, a doctor be consulted.

Though Scovil’s booklet is an instructional text for mothers, it is also a long and illustrated advertisement for Ivory Soap. I don’t know how much Procter and Gamble paid her to promote their product, but she certainly does so with great frequency—to the point of it being amusing. They had no qualms about inserting promotional material within book. For example (one among many), Scovil insists, “A cake of Ivory Soap is within the reach of every mother, and with this she can keep the skin of her children in perfect condition” (26). “Perfect” condition is quite a promise. The amount of promotional material in the text actually made me not take Scovil’s advice as seriously. Though she had her nursing degree and gave seemingly wise advice, the consistent ads within her work made me skeptical. I’m not sure this would have had the same effect on women back in 1906.

Though Scovil’s booklet is an instructional text for mothers, it is also a long and illustrated advertisement for Ivory Soap. I don’t know how much Procter and Gamble paid her to promote their product, but she certainly does so with great frequency—to the point of it being amusing. They had no qualms about inserting promotional material within book. For example (one among many), Scovil insists, “A cake of Ivory Soap is within the reach of every mother, and with this she can keep the skin of her children in perfect condition” (26). “Perfect” condition is quite a promise. The amount of promotional material in the text actually made me not take Scovil’s advice as seriously. Though she had her nursing degree and gave seemingly wise advice, the consistent ads within her work made me skeptical. I’m not sure this would have had the same effect on women back in 1906.

Scovil’s book and Procter and Gamble’s lengthy ad ends very unceremoniously: When referring to the treatment of bites and stings, Scovil advises, “Cover the part affected with a paste made by moistening baking soda with water, or bathe with a teaspoonful of ammonia in a cup of water” (40). The book ends there, leaving the reader to contemplate Scovil’s advice and when she can make her next Ivory Soap purchase.