[Posted by Emily Leonard for AMST 851: The World of Rare Books (Instructor: Richard Ring)]

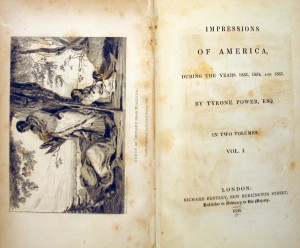

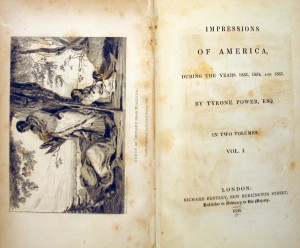

Film buffs think of “Tyrone Power ” as the breathtakingly handsome actor who was 20th Century Fox’s top male attraction from the mid-1930s to early 1950s, starring in such classics as The Mark of Zorro or Witness for the Prosecution. Theatrical cognoscenti know that the real star in the family was the film idol’s great grandfather, the first Tyrone Power, an Irish comedian who packed theaters all over the Continent before his triumphal tour of the United States in 1833, ’34 and ’35. Impressions of America is the record of these travels.

Film buffs think of “Tyrone Power ” as the breathtakingly handsome actor who was 20th Century Fox’s top male attraction from the mid-1930s to early 1950s, starring in such classics as The Mark of Zorro or Witness for the Prosecution. Theatrical cognoscenti know that the real star in the family was the film idol’s great grandfather, the first Tyrone Power, an Irish comedian who packed theaters all over the Continent before his triumphal tour of the United States in 1833, ’34 and ’35. Impressions of America is the record of these travels.

My master’s thesis concerns the early Republic and, among other things, how foreign visitors viewed it. Power’s book is particularly important because, unlike the negative reports of his fellow Britons who traveled in the United States in the 1830s, it provides an appealing picture of an ambitious young nation, a bit bumptious but always sure that its destiny lay west and that any enterprising person could find success if only he looked far enough. Since Frances Trollope, Fanny Kemble, and the great Charles Dickens, among others, could find little to admire and much to condemn in American society, Power’s Impressions of America is essential to the development of my thesis. But there was not a single copy to be found on the Internet, Amazon or in local bookstores. It has never been reprinted and, surprisingly, Project Gutenberg has digitized only the second volume. A search of the Trinity College catalog turned up the first edition, in 2 volumes, at the Watkinson. I could now provide the balance I need for my review of the early Republic. Power’s Impressions of America provides the perfect response to the sharp criticism of observers like Dickens and Captain Frederick Maryatt, whose disdain for all things American so incensed the citizens of Detroit that they hung him in effigy.

Power found the citizens of the young Republic “clear-headed, energetic, frank and hospitable…” (x) His assertion that a “working man at the dinner table was as courteous and well-mannered as the elegant lady who sat next to him” (92) refutes other European travelers’ complaints about “… spitting-boxes, tobacco, two pronged forks…”(346). He had, from the outset, been determined to ignore these minor irritants, while focusing on “the great labors” that were rapidly transforming the nation as it moved west.

The energy and ambition exhibited by the average American made a strong impression on Power. He described “… a community suited to and laboring for their country and its advancement rather than for their own present generation,”(x) noting the many voluntary philanthropic societies devoted to improving community life and, with some amusement, the American predilection for playing soldier as manifest by the ubiquitous musters of militia in towns and villages during the summer months. These glimpses of democracy in action provided a strong contrast to the conditions in Great Britain and Ireland where powerless workers were in virtual bondage to their employers. Indeed, it may well have been the contrast between his down-trodden, near-to-starving Irish compatriots, suffering under the Penal Laws, and the apparently well-fed, decently dressed house slaves Power encountered in his travels in America’s south that made him so tolerant of that ‘peculiar institution.’

“My days were passed at the hospitable house of

Mr. G——n, where I encountered many pleasant

people; and was attended by the sleekest, merriest

set of Negroes imaginable, most of whom had grown

old or were born in their master’s house: his own

good-humoured, active benevolence of spirit was

reflected in the faces of his servants.” (110)

Power’s comments on New Englanders offer some support for this explanation of his failure to condemn slavery. Although he has only praise for Boston’s “…houses of the largest class, well built and kept with the right English spirit as far as regards the scrupulous cleanliness of the entrance areas and windows,” (102) he is not so flattering about the New England character.

“From both the creed and the sumptuary regulations

of the rigid moral censors from which they were spring,

they have inherited a practice of close self-observation

and a strict attention to conventional form which gives a

rigid restraint to their air.” (125)

Or, in the more generous spirit of gentle teasing which is his usual approach to the foibles of Americans in general, he describes a Boston theater audience:

“[it] ‘…is in the character ascribed to New Englanders that

they should coolly and thoroughly examine and understand

the novelty presented for their judgment and, that, being

satisfied and pleased, they should no longer set limits to the

demonstration of their feelings.” (124)

In one area, Power does echo the negative reaction of his fellow travelers. He depletes the way in which new immigrants, especially the Irish, are treated by the native-born. Noting that the Boston’s Tremont Hotel is entirely staffed by Irish lads, he makes a plea for their acceptance into Yankee society, which he characterizes as one with “…many prejudices inseparable from a system of education even to this day sufficiently narrow and sectarian.” (126)

But his major emphasis is on the rapid expansion of the nation, and the people who are accomplishing it:

“…these frontier tamers of the swamp and of the forest:

they are hardy, indefatigable, and enterprising to a degree;

despising and contemning luxury and refinement, courting

labour, and even making a pride of the privations which they,

without any necessity, continue to endure with their families.

They are prudent without being at all mean or penurious, and

are fond of money without having a tittle of avarice. This may

at first sight appear stated from a love of paradox, yet nothing

can be more strictly and simply true; this is, in fact, a singular

race, and they seem especially endowed by Providence to

forward the great work in which they are engaged—to clear the

the wilderness and lay bare the wealth of this rich country with

herculean force and restless perseverance, spurred by a spirit of

acquisition no extent of possession can satiate.” [216]

The paradox here is why the other British travelers’ generally negative reports on America’s citizens in the early Republic which aroused such ire in both the parlor and the press have been reprinted many, many times, while the work of one who saw us as we like to think we were has been so nearly forgotten? Thanks to the Watkinson library and the seventeen other rare book repositories holding copies, Tyrone Power’s Impressions of America will continue to be available for scholars to study the young nation as it was creating the myths and the legends that form our modern understanding of America’s history.

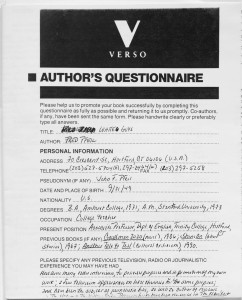

Born and raised in Hartford, Dr. Evald L. Skau (Norwegian, pronounced “sk-ow”), was no stranger to winning prizes. As a child, he won the Sunday Globe’s freehand drawing prize, and he also took home the boy’s story prize for his “My Dream About My Kite.”

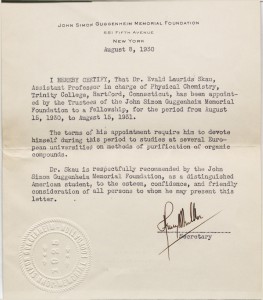

Born and raised in Hartford, Dr. Evald L. Skau (Norwegian, pronounced “sk-ow”), was no stranger to winning prizes. As a child, he won the Sunday Globe’s freehand drawing prize, and he also took home the boy’s story prize for his “My Dream About My Kite.” He then went on to win many awards at Trinity, Yale, and the United States Department of Agriculture. By far his most prestigious award, however, was his 1930 Guggenheim Fellowship, which enabled him to spend two years in Europe studying the purification of organic compounds and made him the first professor in Trinity history to be so honored.

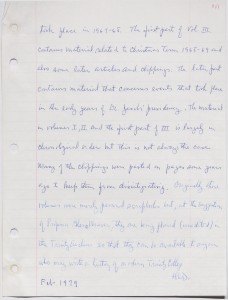

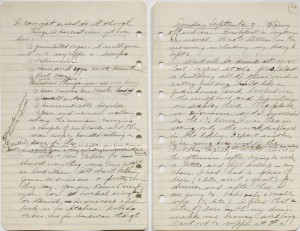

He then went on to win many awards at Trinity, Yale, and the United States Department of Agriculture. By far his most prestigious award, however, was his 1930 Guggenheim Fellowship, which enabled him to spend two years in Europe studying the purification of organic compounds and made him the first professor in Trinity history to be so honored. “Things I haven’t seen yet over here: 1. granulated sugar- it is always given out with [unclear] coffee in lumps, 2. Watermelon, 3. Ham and eggs as we know them, 4. Root beer, 5. Good movies

“Things I haven’t seen yet over here: 1. granulated sugar- it is always given out with [unclear] coffee in lumps, 2. Watermelon, 3. Ham and eggs as we know them, 4. Root beer, 5. Good movies