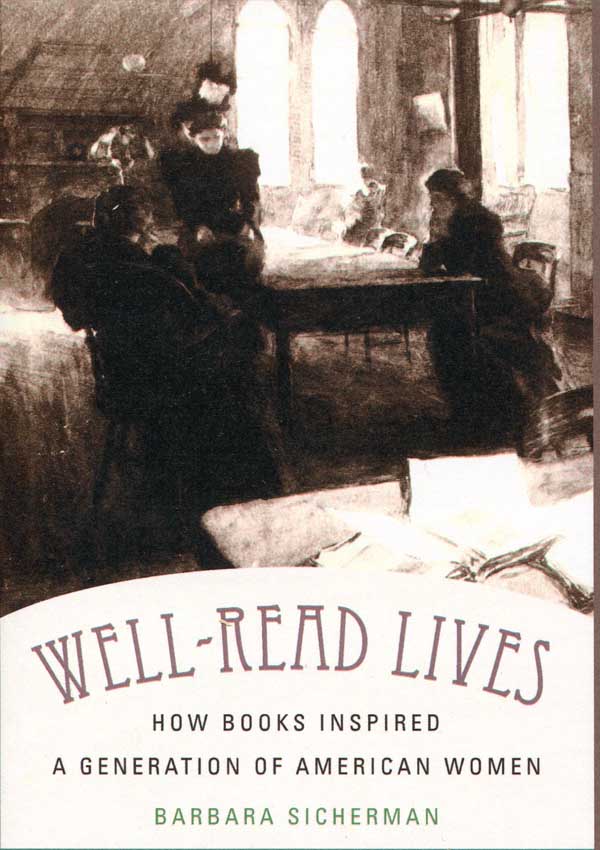

Last night we had a nice group of about 25-30 people at our event, sponsored by the Trinity College and Watkinson Library Associates: a talk and book signing with Professor Emerita, Barbara Sicherman, in celebration of her book, Well-Read Lives: How Books Inspired a Generation of American Women.

Last night we had a nice group of about 25-30 people at our event, sponsored by the Trinity College and Watkinson Library Associates: a talk and book signing with Professor Emerita, Barbara Sicherman, in celebration of her book, Well-Read Lives: How Books Inspired a Generation of American Women.

I put up a small display of books that Dr. Sicherman discussed in her book–all first editions. Here they are (with one exception, all quotes are from Sicherman’s book):

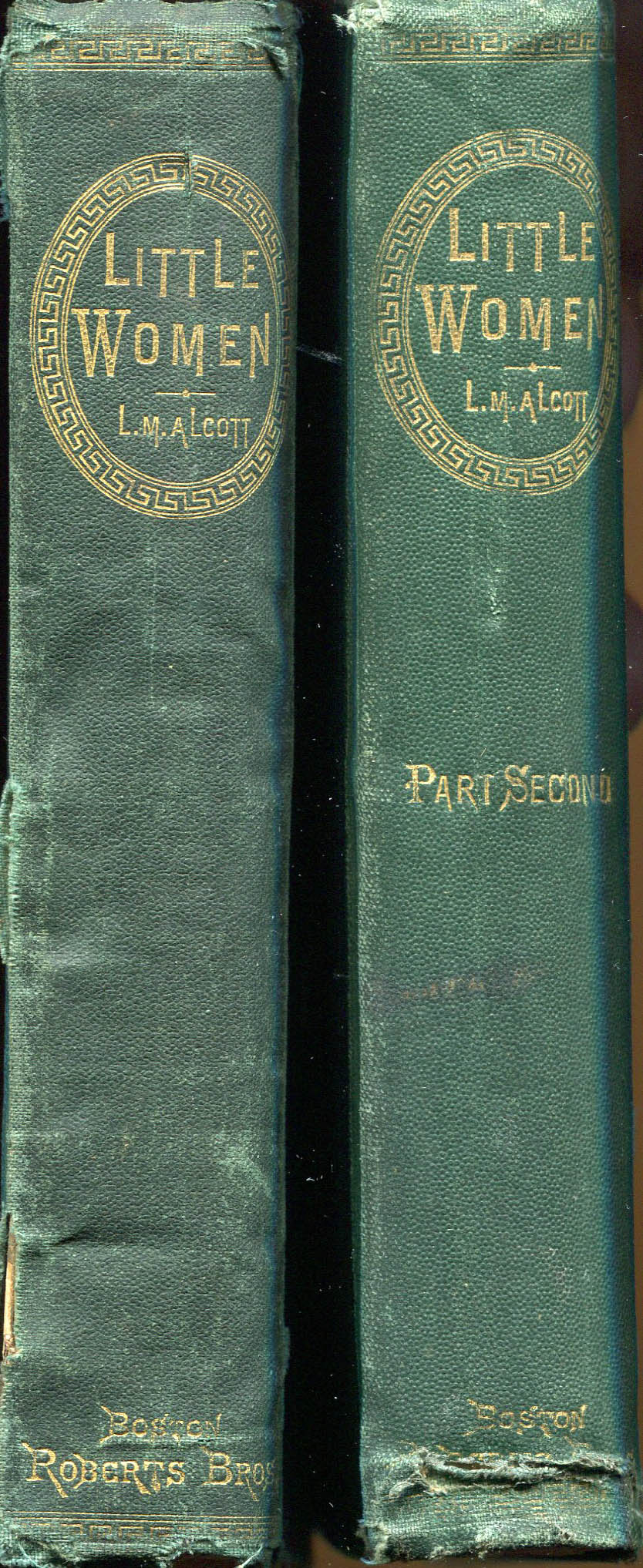

Little Women, by Louisa May Alcott. (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1868 (part I) and 1869 (part II)).

I read Little Women a thousand times. Ten thousand. I am no longer incognito, not even to myself. I am Jo in her ‘vortex;’ not Jo exactly, but some Jo-of-the-future. I am under an enchantment: Who I truly am must be deferred, waited for and waited for. —Cynthia Ozick (1982)

I read Little Women a thousand times. Ten thousand. I am no longer incognito, not even to myself. I am Jo in her ‘vortex;’ not Jo exactly, but some Jo-of-the-future. I am under an enchantment: Who I truly am must be deferred, waited for and waited for. —Cynthia Ozick (1982)

“As a character readers imagined becoming, Jo promoted self-discovery, revealing hidden potentialities to those in the liminal state between childhood and adulthood.” [15]

The Wide, Wide World, by Susan Bogert Warner [writing as Elizabeth Wetherell] (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1851). AND Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Life Among the Lowly, by Harriet Beecher Stowe. (Boston: John P. Jewett & Co., 1852).

The Wide, Wide World, by Susan Bogert Warner [writing as Elizabeth Wetherell] (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1851). AND Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Life Among the Lowly, by Harriet Beecher Stowe. (Boston: John P. Jewett & Co., 1852).

“[I]t was as fiction writers that women attained their greatest success. They not only wrote almost three quarters of the novels published in the United States by 1872, but were among the best-selling authors of the era. Beginning with Susan Warner’s The Wide, Wide World (1851), many “women’s novels” sold more than 100,000 copies. Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), the best-selling novel of the century, sold an estimated 300,000 copies within the first year and half a million in the United States alone by the end of the fifth. Hawthorne’s dig at the “damned mob of scribbling women” was not just a manner of speaking, but a pained recognition of women’s astonishing popularity—and financial success—in the field of literature.” [39]

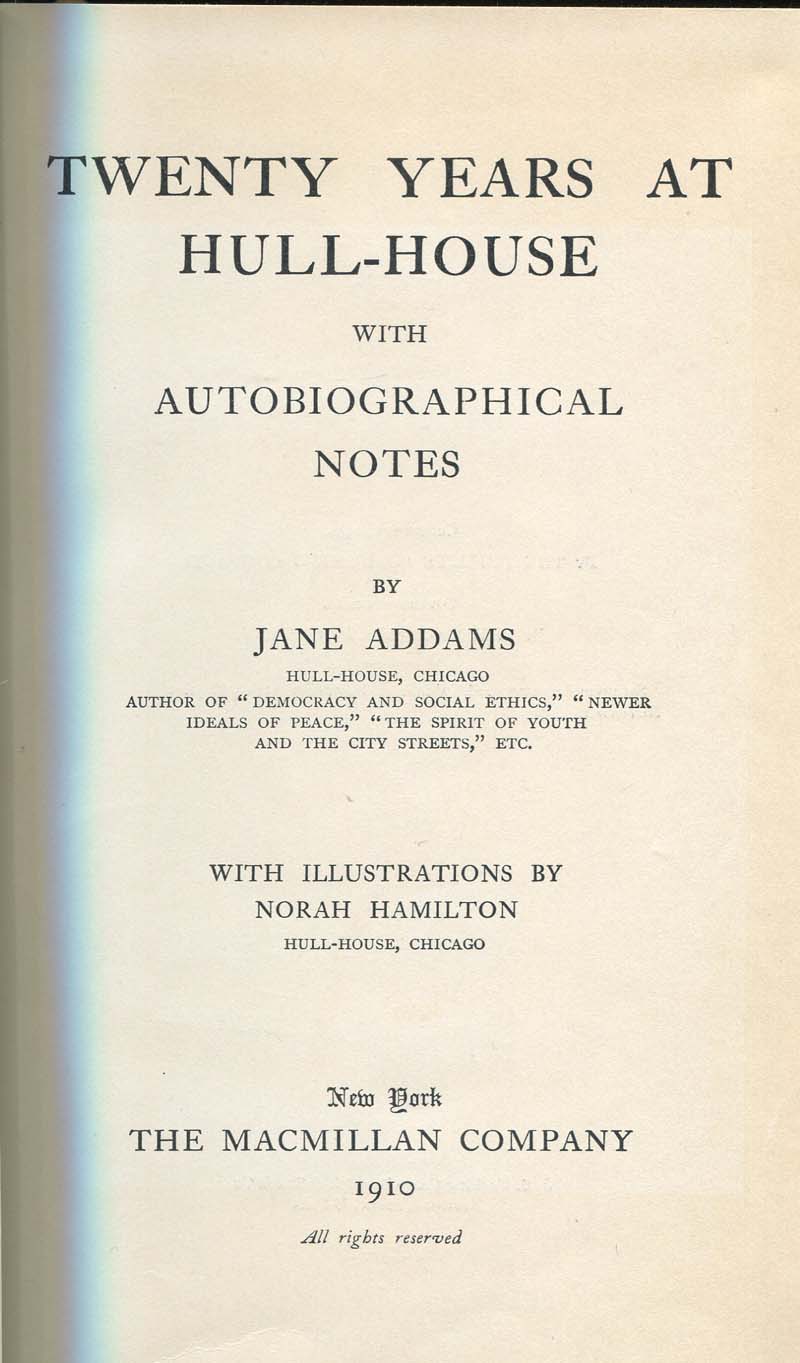

Twenty Years at Hull-House, with Autobiographical Notes, by Jane Addams. (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1910).

“When Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr took up residence at 335 Halstead Street in Chicago in September 1889, they hoped that by sharing their lives with their mainly immigrant neighbors they would find ways to help bridge the gulf between the city’s haves and have-nots . . . The women’s initiative in founding one of the first settlement houses proved to be a harbinger of one of the great social movements of the age: by 1900, there were more than 100 settlements in the United States.” [165]

“When Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr took up residence at 335 Halstead Street in Chicago in September 1889, they hoped that by sharing their lives with their mainly immigrant neighbors they would find ways to help bridge the gulf between the city’s haves and have-nots . . . The women’s initiative in founding one of the first settlement houses proved to be a harbinger of one of the great social movements of the age: by 1900, there were more than 100 settlements in the United States.” [165]

“Like other institutions with a mission to improve the lives of the underprivileged, Hull-House became a sponsor of culture, a term used here to include educational and cultural ventures designed to extend the intellectual and social horizons of local inhabitants. The expansion of the original mansion to thirteen buildings occupying a full city block gave visual testimony to the settlement’s cultural reach. At its peak it encompassed three formal theater groups, art and music schools, a women’s symphony orchestra, a chorus of 500 ‘working people,’ and clubs of every description, not to mention girls’ and boys’ basketball teams.” [166]

The Second Twenty Years at Hull-House, September 1909 to September 1929, with a Record of a Growing World Consciousness, by Jane Addams. (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1930).

The Second Twenty Years at Hull-House, September 1909 to September 1929, with a Record of a Growing World Consciousness, by Jane Addams. (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1930).

“In The Second Twenty Years at Hull-House (1930), Jane Addams expressed puzzlement at the ‘contrasts in a post-war generation,’ including younger women’s lack of interest in the social ideals that animated her contemporaries and the new emphasis on sex as the most important avenue for fulfillment. While it is true that young women no longer had the same sense of gender consciousness—in its dual connotation of privilege and obligation—that motivated many women of Addams’s generation, they did not simply opt for exclusively private lives. But most were unwilling to make the choice between career and marriage that their predecessors took for granted. Fortified by the vote, and not much interested in female bonding, successive generations of women learned firsthand what the Progressive generation had assumed: that without institutional supports, career and motherhood were difficult to combine.” [253]

Tags: Events