Manchester, CT physician Dr. Tris Carta and Angelee Diana Carta ’77, P ’11, gave several nice 19th-century medical books to the Library, which will enhance our already nice array of items on the spectrum from quackery to the latest scientific works. Three of the books are detailed here:

Burney James Kendall (1845-1922) was an 1868 graduate of the University of Vermont’s Medical College. During the 1870s, he devised a “cure” for spavin (an equine joint ailment), and incorporated the Dr. B. J. Kendall Company in 1883 to manufacture his horse liniment. The company’s product line gradually expanded to include treatments for a wide variety of animal and human ailments, and the company’s wagons ranged far and wide selling the medicines and distributing booklets–such as A Treatise on the Horse and His Diseases (a copy of which is already in the Watkinson) and The Doctor at Home. Illustrated. Treating the Diseases of Man and the Horse (the copy shown here, published in 1884, was recently given to us by a physician in Manchester). According to the “publisher’s announcement,”we feel assured that we are supplying one of the greatest lacks in every household, by placing therein a work so plain and simple in its language that the most ignorant will have no difficulty in understanding it . . . if you cannot find all the information you desire by carefully studying this book, your case is probably one which should have the attention of some intelligent physician.”

Burney James Kendall (1845-1922) was an 1868 graduate of the University of Vermont’s Medical College. During the 1870s, he devised a “cure” for spavin (an equine joint ailment), and incorporated the Dr. B. J. Kendall Company in 1883 to manufacture his horse liniment. The company’s product line gradually expanded to include treatments for a wide variety of animal and human ailments, and the company’s wagons ranged far and wide selling the medicines and distributing booklets–such as A Treatise on the Horse and His Diseases (a copy of which is already in the Watkinson) and The Doctor at Home. Illustrated. Treating the Diseases of Man and the Horse (the copy shown here, published in 1884, was recently given to us by a physician in Manchester). According to the “publisher’s announcement,”we feel assured that we are supplying one of the greatest lacks in every household, by placing therein a work so plain and simple in its language that the most ignorant will have no difficulty in understanding it . . . if you cannot find all the information you desire by carefully studying this book, your case is probably one which should have the attention of some intelligent physician.”

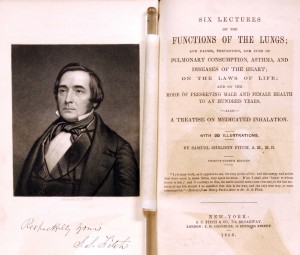

Signed by the author, American physician and founder of a patent medicine company, Dr. Samuel Sheldon Fitch (1801-1876) received his medical degree from Jefferson Medical College of Philadelphia in 1828. He began trading under the name “Dr. S. S. Fitch,” and about 1851 he began issuing almanacs, Dr. S.S. Fitch’s Almanac and Guide to Invalids, which promoted his patent medicines and medical devices, and prescribes health regimens and cures for consumption, asthma, heart diseases, bronchitis, head-aches, dyspepsia, ague and fever, liver complaint, diarrhoea, baldness and hair loss, and whatever else ailed you. An advertisement in the 1854 Boston Herald annouced that a local doctor was the “Agency for Dr. S.S. Fitch’s Celebrated Medicines and Mechanical Remedies for cure of Consumption, Asthma, Female Diseases, etc.”. Included are testimonial letters from former patients, advice to “Invalid Ladies” & “Invalid Gentlemen,” and discussions of such topics as the function of the lungs & causes of consumption, cure of throat diseases, cold bathing, diet, spinal diseases, diseases of the heart, asthma, the effects of dancing, the use of inhaling tubes, the effect of journeys, sea voyages, and warm climate, among many others.

Signed by the author, American physician and founder of a patent medicine company, Dr. Samuel Sheldon Fitch (1801-1876) received his medical degree from Jefferson Medical College of Philadelphia in 1828. He began trading under the name “Dr. S. S. Fitch,” and about 1851 he began issuing almanacs, Dr. S.S. Fitch’s Almanac and Guide to Invalids, which promoted his patent medicines and medical devices, and prescribes health regimens and cures for consumption, asthma, heart diseases, bronchitis, head-aches, dyspepsia, ague and fever, liver complaint, diarrhoea, baldness and hair loss, and whatever else ailed you. An advertisement in the 1854 Boston Herald annouced that a local doctor was the “Agency for Dr. S.S. Fitch’s Celebrated Medicines and Mechanical Remedies for cure of Consumption, Asthma, Female Diseases, etc.”. Included are testimonial letters from former patients, advice to “Invalid Ladies” & “Invalid Gentlemen,” and discussions of such topics as the function of the lungs & causes of consumption, cure of throat diseases, cold bathing, diet, spinal diseases, diseases of the heart, asthma, the effects of dancing, the use of inhaling tubes, the effect of journeys, sea voyages, and warm climate, among many others.

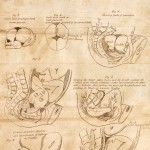

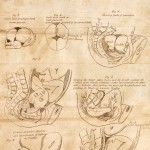

Thomas Ewell (1785-1826) was a Virginia-born physician who studied under (among others) Dr. Benjamin Rush at the University of Pennsylvania, and served as a naval surgeon in Washington from 1808-1813. He is said to have invented and used a method of making gunpowder by rolling, instead of the (more dangerous) pounding method. The Letters to Ladies (1817), shown here, included a project for establishing a large lying-in hospital in Washington through a nation-wide fundraising effort. The obstetrical engraving (right) is particularly interesting.

Thomas Ewell (1785-1826) was a Virginia-born physician who studied under (among others) Dr. Benjamin Rush at the University of Pennsylvania, and served as a naval surgeon in Washington from 1808-1813. He is said to have invented and used a method of making gunpowder by rolling, instead of the (more dangerous) pounding method. The Letters to Ladies (1817), shown here, included a project for establishing a large lying-in hospital in Washington through a nation-wide fundraising effort. The obstetrical engraving (right) is particularly interesting.

Ewell was (according to the Dictionary of American Biography) “a man of distinguished professional attainments and marked talent for research and invention, with a turn for ridicule, however, and convivial habits which weakened his health.”

“The Blue-green Warbler has a peculiar cunning manner of leaning downwards to view a person, or while searching for an insect, and which is very different from that of any other bird, although I am unable to describe it. While thus leaning, it moves its head sideways so very slowly that the motion is hardly perceptible, unless much attention is paid to it. After this, it either starts off and flies to some distance from the observer, or darts towards the prey that had attracted its notice. While catching an insect on the wing, it produces a slight clicking sound with its bill, and in this respect approaches the Vireos. Like some of them also, it descends from the highest tops of the trees to low bushes, and eats small berries, particularly towards autumn, when insects begin to fail . . .

“The Blue-green Warbler has a peculiar cunning manner of leaning downwards to view a person, or while searching for an insect, and which is very different from that of any other bird, although I am unable to describe it. While thus leaning, it moves its head sideways so very slowly that the motion is hardly perceptible, unless much attention is paid to it. After this, it either starts off and flies to some distance from the observer, or darts towards the prey that had attracted its notice. While catching an insect on the wing, it produces a slight clicking sound with its bill, and in this respect approaches the Vireos. Like some of them also, it descends from the highest tops of the trees to low bushes, and eats small berries, particularly towards autumn, when insects begin to fail . . .