I saw the following description of a book for sale in the trade and discovered to my relief that we

had a copy!

Francis Douce (1757-1834) was the youngest son of a lawyer, who (much to his father’s dismay) was only interested in literary and antiquarian research, not a profession in law. According to the

DNB, “He succeeded to a smaller share of his father’s property than he had anticipated, and attributed his disappointment to the ‘misrepresentation’ of his elder brother, ‘who used to say it was no use to leave me money, for I should waste it on books.'”

Illustrations of Shakespeare, and of ancient manners: With dissertations of the clowns and fools of Shakspeare; on the collection of popular tales entitled Gesta romanorum; and on the English morris dance. London, 1807.

This is Douce’s commentary on obscure points of Shakespeare’s plays, examining possible source materials and often focusing on the anachronisms present in the plots and settings. Includes the legalities of different types of marriage contracts, the nature of period music (offering as examples tunes for the “Scotish brawl” and “Canary”), and the fine details of such activities as quail fighting, crow keeping, wassail drinking, wearing chopines, furnishing funeral tables, etc., as well as longer researches on the subjects described in the title. The work was generally well-received at the time of its publication, and a later 19th-century critic praised Douce for his “delicate and sympathetic apprehension of the peculiar beauties of Shakespeare,” but Jeffrey rather famously severely critiqued the work in the Edinburgh Review, and Stapfer described it as “bristling with erudition but devoid of talent, and very foolish and irreverent towards Shakespeare.”

Two examples of his topics follow:

O beat away the busy meddling fiend / That lays strong siege unto this wretch’s soul.

[King Henry VI, part 2, Act III, scene 3]

“It was the belief of our pious ancestors, that when a man was on his death-bed the devil or his agents attended in the hope of getting possession of the soul, if it should happen that the party died without receiving the sacrament of the Eucharist, or without confessing his sins. Accordingly in the ancient representations of this subject, and more particularly in those which occur in such printed services of the church as contain the vigils or office of the dead, these busy, meddling fiends appear, and with great anxiety besiege the dying man; but on the approach of the priest and his attendants, they betray symptoms of horrible despair at their impending discomfiture. In an ancient manuscript book of devotions, written in the reign of Henry the Sixth, there is a prayer addressed to Saint George, with the following very singular passage: ‘Judge for me whan the moste hedyous and damnable dragons of helle shall be redy to take my poore soule and engloute it in to theyr infernall belyes.'”

In his section “On the clowns and fools of Shakespeare,” Douce creates a classification of nine (9) types, including:

I. The general domestic fool, often, but as it should seem improperly, termed a clown. He was 1. a mere natural, or idiot. 2. Silly by nature, yet cunning and sarcastical. 3. Artificial

II. The clown, who was 1. a mere country booby. 2. A witty rustic. 3. Any servant of a shrewd and witty disposition.

III. The female fool, who was generally an idiot.

IV. The city or corporation fool, whose office was to assist at public entertainments and pageants.

V. Tavern fools. These seem to have been retained to amuse the customers.

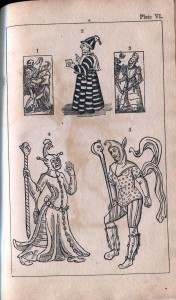

“Plate VI: Fig. 1 and 3 are from A booke of Christian prayers, &c., 1590, being figures belonging to a dance of Death. Fig. 2, is from the frontispiece to Heywood’s comedy of The fair maid of the exchange. Similar figures of the costume of fools in the time of James I., or Charles I., may be seen in the Life of Will Summers, compiled long after his time. Fig. 4 and 5 are from La grant danse Macabre, printed at Troyes without a date, but about the year 1500, in folio, a book of uncommon rarity and curiosity.”

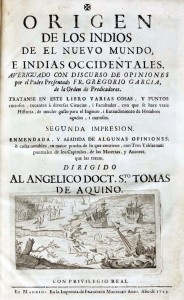

García, Gregorio. Origen de los Indios de el Nueuo Mundo, e Indias Occidentales. (Madrid, 1729).

García, Gregorio. Origen de los Indios de el Nueuo Mundo, e Indias Occidentales. (Madrid, 1729).