On Friday morning we hosted a group of high school seniors from Enfield, some from an English class but most from a philosophy course taught by Kelly Mazzone (nee O’Connor), who took an M.A. from Trinity in History in 2007 (under direction of the late Jack Chatfield).

On Friday morning we hosted a group of high school seniors from Enfield, some from an English class but most from a philosophy course taught by Kelly Mazzone (nee O’Connor), who took an M.A. from Trinity in History in 2007 (under direction of the late Jack Chatfield).

The students have been studying excerpts from Genesis, the works of St. Anselm, St. Tomas Aquinas, William Paley and Blaise Pascal, as well as passages from Milton and Dante. They seemed pretty excited and engaged when I laid out for them our editions of Paradise Lost (in ten books, 1668, and in twelve books, 1678, including a copy formerly owned by John Eliot), and several edition s of the Inferno.

Also of interest to them were our original leaf (and newly acquired facsimile of) the Gutenberg Bible, the first volumes of two of the major polyglot Bibles–Paris (1645) and London (1657)–and the 1611 first edition of the “King James Version,” not to mention two of our beautiful books of hours, and (in answer to, “what is your oldest book”?), our cuneiform tablet.

I think a few bibliophiles were born that morning–or at least, definitley quickened!

Comments Off on God & Evil in the Watkinson

This week saw a rare happening in the Watkinson: two presentations using the exact same materials for separate classes at separate institutions!

On Monday night, profesor Scott Gac (Trinity) brough his HIST 354 class in to look at materials related to slavery in the Watkinson, which included a set of slave shackles recently donated to us, two manumission documents, and two bills of sale for slaves.

On Monday night, profesor Scott Gac (Trinity) brough his HIST 354 class in to look at materials related to slavery in the Watkinson, which included a set of slave shackles recently donated to us, two manumission documents, and two bills of sale for slaves.

On Tuesday night, professors Bryan Sinche and Sarah Senk (University of Hartford) brought the students in a Senior Capstone Course to look at the very same items, with the addition of published slave narratives and publications of the American Colonization Society–including our very fragile issues of The Liberia Herald.

On Tuesday night, professors Bryan Sinche and Sarah Senk (University of Hartford) brought the students in a Senior Capstone Course to look at the very same items, with the addition of published slave narratives and publications of the American Colonization Society–including our very fragile issues of The Liberia Herald.

Comments Off on A teaching two-fer

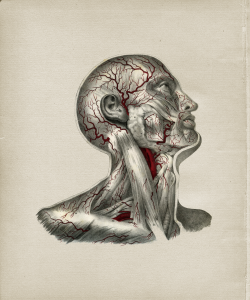

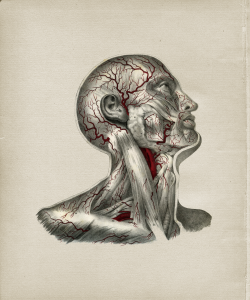

On Tuesday, a dozen first-year students participating in the Bantam Beginnings program came to the Watkinson Library to look at several rare books featuring anatomical illustrations from the 16th-19th centuries. Each student was to select a particular organ, system, etc. and compare how early anatomical illustrations compare to 21st century depictions. This was part of The Skill in Observation and Communication in Art and Medicine program, facilitated by Professor William Church.

On Tuesday, a dozen first-year students participating in the Bantam Beginnings program came to the Watkinson Library to look at several rare books featuring anatomical illustrations from the 16th-19th centuries. Each student was to select a particular organ, system, etc. and compare how early anatomical illustrations compare to 21st century depictions. This was part of The Skill in Observation and Communication in Art and Medicine program, facilitated by Professor William Church.

We had set out 9 books, all open to anatomy illustrations. The students were not only engaged with the material, but also asked many questions—both about content and the books themselves. In several cases, the students asked for dictionaries to look up terms that they didn’t understand instead of turning immediately to the internet for answers. The class was with us for about an hour with the students congregating around several of the texts, carrying on discussions about the content that ranged from questions about the images: “What is that?” “Is that a hip?” “What part of the brain is that?” “Are those lines veins coming out of the muscles?”

They were also curious about the way the images were depicted—questioning the artistic merit/content/liberties—and asking if the images were typical of anatomy books, or of iconography found in art of the period. One of the more interesting conversations that seemed to stem from the images was how the bodies for dissection were obtained. When one of the students realized that the bodies were often of the poor, lower classes, or prisoners, she took another look at the muscles that were depicted on the skeleton and said; “Then I guess he wasn’t the most muscular specimen that they could find!”

They were also curious about the way the images were depicted—questioning the artistic merit/content/liberties—and asking if the images were typical of anatomy books, or of iconography found in art of the period. One of the more interesting conversations that seemed to stem from the images was how the bodies for dissection were obtained. When one of the students realized that the bodies were often of the poor, lower classes, or prisoners, she took another look at the muscles that were depicted on the skeleton and said; “Then I guess he wasn’t the most muscular specimen that they could find!”

Students were particularly fascinated by illustrations in A series of anatomical plates; with references and physiological comments by Jones Quain and W.J. E. Wilson, published in 1842. This work stimulated many questions about specific organs and systems. Also of great interest was the classic work Medici De humani corporis fabrica libri septem : Cum indice rerum & uerborum memorabilium locupletissimo, by Andreas Vesalius, published in 1568.

Students were particularly fascinated by illustrations in A series of anatomical plates; with references and physiological comments by Jones Quain and W.J. E. Wilson, published in 1842. This work stimulated many questions about specific organs and systems. Also of great interest was the classic work Medici De humani corporis fabrica libri septem : Cum indice rerum & uerborum memorabilium locupletissimo, by Andreas Vesalius, published in 1568.

[Posted by Watkinson staff Henry Arneth & Peter Rawson]

Comments Off on Name that body part!

We were thrilled yet again to have a steady stream of visitors on Saturday of Commencement Weekend, many of whom were urged to visit by President Jones, who has always been a staunch supporter of the Watkinson.

We were thrilled yet again to have a steady stream of visitors on Saturday of Commencement Weekend, many of whom were urged to visit by President Jones, who has always been a staunch supporter of the Watkinson.

In all we had 113 people, including students and their families, as well as random alumni, wander in between Noon and 3pm, who came to view our featured items:

Lucky 13!, a “baker’s dozen” of student exhibitions in the Watkinson Library including Native American education movements, explorations of Latino identity through artists’ books, 19th-century tourism in the Hudson Valley, the history of the Hartford Insane Asylum, and the works of Beatrix Potter.

Lucky 13!, a “baker’s dozen” of student exhibitions in the Watkinson Library including Native American education movements, explorations of Latino identity through artists’ books, 19th-century tourism in the Hudson Valley, the history of the Hartford Insane Asylum, and the works of Beatrix Potter.

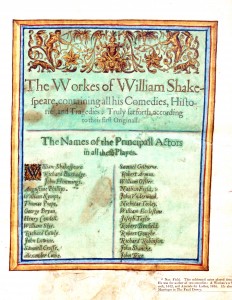

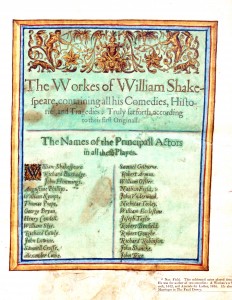

The so-called “2nd Folio” of Shakespeare’s plays, acquired in 2012, which was published in 1632, nine years after the landmark “First Folio” of 1623 (in which eighteen of Shakespeare’s plays were published for the first time). The 1632 edition bore over 1,200 corrections as well as the first published poem by John Milton.

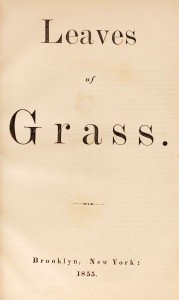

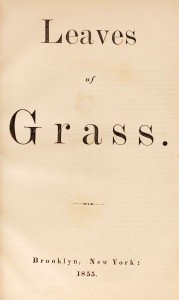

The first edition (Brooklyn, 1855) of Walt Whitman’s

Leaves of Grass, which the poet self-published (he also designed the binding and set some of the type). Just acquired, this literary landmark has been considered America’s

second Declaration of Independence, in terms of its radical break with European literary culture and distinctly American voice.

John James Audubon’s Birds of America (1826-39). Given in 1900, this is by far the most valuable book at Trinity. We began turning the page to a new bird every week in September 2011. We are halfway through Volume II, and will get through the entire 4-volume set sometime in 2019.

Comments Off on Commencement 2014

The Watkinson is a favorite stop for those touring the College Library, and we have given half a dozen tours this summer to kids from the magnet school across the street from Trinity. Most of these middle school kids shuffle through without asking questions, but I often hear later that they are really interested. Certainly the highpoint this year is our demonstration of a 1920’s victrola that we do–it is amazing for them to see a non-electronic device produce music fit to dance to! See the play in action on our previous post.

Comments Off on School tours

On Monday night, profesor Scott Gac (Trinity) brough his HIST 354 class in to look at materials related to slavery in the Watkinson, which included a set of slave shackles recently donated to us, two manumission documents, and two bills of sale for slaves.

On Monday night, profesor Scott Gac (Trinity) brough his HIST 354 class in to look at materials related to slavery in the Watkinson, which included a set of slave shackles recently donated to us, two manumission documents, and two bills of sale for slaves. On Tuesday night, professors Bryan Sinche and Sarah Senk (University of Hartford) brought the students in a Senior Capstone Course to look at the very same items, with the addition of published slave narratives and publications of the American Colonization Society–including our very fragile issues of The Liberia Herald.

On Tuesday night, professors Bryan Sinche and Sarah Senk (University of Hartford) brought the students in a Senior Capstone Course to look at the very same items, with the addition of published slave narratives and publications of the American Colonization Society–including our very fragile issues of The Liberia Herald.