From the Archivist’s Perspective: Feature Columns and Articles by Peter Knapp in the Trinity Reporter, 1976-2012

From the Archivist’s Perspective: Feature Columns and Articles by Peter Knapp in the Trinity Reporter, 1976-2012

The Watkinson Library and Trinity College plan to publish a volume honoring the retirement of College Archivist Peter Knapp, which will occur on August 29, 2014. Mr. Knapp is himself a Trinity institution. Graduating with the Class of 1965, he received his M.A. in History from the University of Rochester and a Master’s in Library Science from Columbia University. He was hired by the Trinity College Library in 1968 as Head of Reference.

In 1972 Mr. Knapp also took on the development of the College Archives, and soon began writing articles on Trinity’s history for the Reporter. He would ultimately collaborate with his wife, Anne H. Knapp, to produce Trinity College in the Twentieth Century: A History (2000), intended as a second volume to Glen Weaver’s 1967 History of Trinity College.

The prospective publication of 40 short essays concerning Trinity history that Mr. Knapp wrote for the Trinity Reporter, including a few excerpts from Peter’s book-length study, also includes one original contribution never before published, on Trinity men who served in the Civil War (on both sides!).

More information about this publication is forthcoming!

Theodore Roosevelt speaks at Commencement

Theodore Roosevelt speaks at Commencement

Building the Chapel

Comments Off on He Wrote the Book on Trinity

In 1792 the comparatively unsuccessful Shakespearean Joseph Ritson had launched a direct assault on Edmund Malone’s 1790 edition, claiming that he wished “to rescue the language and sense” of Shakespeare “from the barbarism and corruption they have acquired in passing through the hands of this incompetent and unworthy editor,” and caricatured Malone as a “Paddy from Cork” Irishman.

In 1792 the comparatively unsuccessful Shakespearean Joseph Ritson had launched a direct assault on Edmund Malone’s 1790 edition, claiming that he wished “to rescue the language and sense” of Shakespeare “from the barbarism and corruption they have acquired in passing through the hands of this incompetent and unworthy editor,” and caricatured Malone as a “Paddy from Cork” Irishman.

In 1792 Malone proposed “a new and splendid edition” in fifteen large volumes, but the publisher cancelled his contract due to slow sales.

Although we LACK the 1790 edition, we have the Malone-James Boswell edition of 1821, which was the final realization of Malone’s vision of 1792.

Andrew Murphy, Shakespeare in Print (Cambridge UP, 2003)

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (14): Edmund Malone’s edition

Literary historian George Churchill, writing in 1906, observed (with a typically imperialist tone) that a “people that is winning the soil out of the wilderness and defending itself against savages has no thought of literature, much less of stage-plays,” and further noted that “Massachusetts was a Puritan state, founded by the kin of those of those men who in England attacked so bitterly the stage of Shakespeare. Pennsylvania was a Quaker colony, and the serious views of the Quaker gave no more countenance to the drama than did the austere and ascetic Calvinism of the Puritan.”

Literary historian George Churchill, writing in 1906, observed (with a typically imperialist tone) that a “people that is winning the soil out of the wilderness and defending itself against savages has no thought of literature, much less of stage-plays,” and further noted that “Massachusetts was a Puritan state, founded by the kin of those of those men who in England attacked so bitterly the stage of Shakespeare. Pennsylvania was a Quaker colony, and the serious views of the Quaker gave no more countenance to the drama than did the austere and ascetic Calvinism of the Puritan.”

Records indicate that among the first copies of Shakespeare in America were ones bought by New England Courant Editor James Franklin (in 1722), Harvard (in 1723, which had purchased Rowe’s 1709 edition), Yale (which listed an edition in the 1743 library catalogue), and in 1746 by the Library Company of Philadelphia (the Hanmer edition).

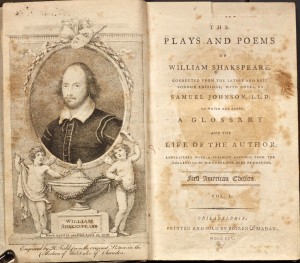

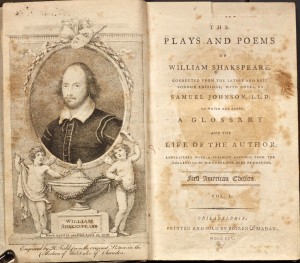

The 1795 Philadelphia complete works, which we have in the Watkinson, was the first edition of Shakespeare to be produced outside of Great Britain. Alfred Van Rensselaer Westfall has tentatively identified the editor as Joseph Hopkinson, a prominent Philadelphia lawyer, observing that his work on the edition “leaves little to his credit,” as he hardly did more than “hand the printer a glossary from one edition, the text from a second, and a few notes from a third.” Interestingly, the bulk of the preface is taken up with a defense of Shakespeare’s works against the charge of immorality.

Andrew Murphy, Shakespeare in Print (Cambridge UP, 2003)

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (13): First American edition

One of the big gaps in our collection is the first edition of Samuel Johnson’s text of Shakespeare, published in London in 1765 (8 volumes), and followed immediately that same year with a second edition. The third edition was published in 1768 in London (10 volumes).

One of the big gaps in our collection is the first edition of Samuel Johnson’s text of Shakespeare, published in London in 1765 (8 volumes), and followed immediately that same year with a second edition. The third edition was published in 1768 in London (10 volumes).

We ALSO LACK the “Johnson-Steevens” edition published in London, 1773 (10 volumes), and the Johnson-Steevens-Reed editions of 1778 (London, 10 vols.) and 1785 (Dublin, 10 vols.).

We do, however, have the 1793 Johnson-Steevens-Reed edition, which is the earliest version of Johnson’s Shakespeare we have in the Watkinson. Perhaps some generous alum has a copy of the 1765 edition? We would love to own it!

In 1783, Steevens wrote to Reed, asking him to assume control of the next planned revision of the text, and provided Reed with “some 445 additions, revisions, and omissions in his own 1773 notes.” Johnson himself died in 1784, but his name continued to appear on the title-pages of the Steevens-Reed sequence. Though he had handed control of the text to Reed for the 1785 edition, Steevens resumed control for this edition of 1793, using it as a platform to attack fellow Shakespearean Edmond Malone through his proxy Joseph Ritson, who in 1792 launched a direct assault on Malone, claiming that he wished “to rescue the language and sense” of Shakespeare “from the barbarism and corruption they have acquired in passing through the hands of this incompetent and unworthy editor,” and caricatured Malone as a “Paddy form Cork” Irishman.

Andrew Murphy, Shakespeare in Print (Cambridge UP, 2003)

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (12): Johnson-Steevens-Reed edition

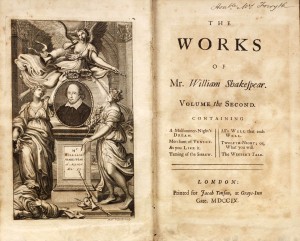

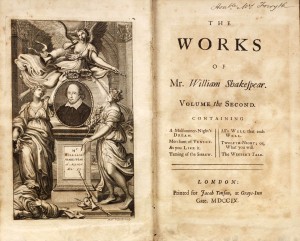

The edition of Shakespeare by Joseph Rann. This is an undistinguished publication from a scholarly point of view, but attractively printed. Joseph Rann (1733-1811), who was from Birmingham, was educated at Trinity College Oxford, and became vicar of Holy Trinity Coventry, a benefice he held for almost forty years.

The edition of Shakespeare by Joseph Rann. This is an undistinguished publication from a scholarly point of view, but attractively printed. Joseph Rann (1733-1811), who was from Birmingham, was educated at Trinity College Oxford, and became vicar of Holy Trinity Coventry, a benefice he held for almost forty years.

Andrew Murphy, Shakespeare in Print (Cambridge UP, 2003)

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (11): Joseph Rann edition (1786-91)

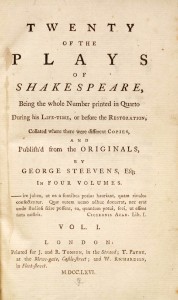

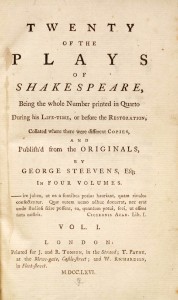

George Steevens (1736-1800) was born of wealthy parents, attended Eton and King’s College (Cambridge), and set about a career as an independent scholar, specializing mainly in Shakespeare.

George Steevens (1736-1800) was born of wealthy parents, attended Eton and King’s College (Cambridge), and set about a career as an independent scholar, specializing mainly in Shakespeare.

The edition shown here is a selection of “the whole number printed in quarto during his lifetime, or before the restoration,” the texts of which Steevens apparently obtained from David Garrick.

Andrew Murphy, Shakespeare in Print (Cambridge UP, 2003)

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (10): the Steevens “20 plays” edition of 1766

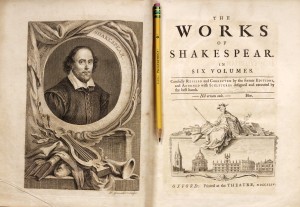

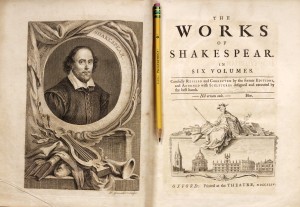

Sir Thomas Hanmer (1677-1746) was Speaker of the House of Commons from 1714-15, thought of himself as a serious editor, who probably had the idea of editing Shakespeare after Theobald’s edition came out (Hanmer’s annotated copy of Theobald is in the Folger Shakespeare Library).

Sir Thomas Hanmer (1677-1746) was Speaker of the House of Commons from 1714-15, thought of himself as a serious editor, who probably had the idea of editing Shakespeare after Theobald’s edition came out (Hanmer’s annotated copy of Theobald is in the Folger Shakespeare Library).

Generally disregarded as an editorial effort, it is also hailed as a beautifully produced and illustrated book, and was a commercial success.

Shown here is a later edition (1751) in smaller format–the same pencil is scanned with both to show relative size.

Shown here is a later edition (1751) in smaller format–the same pencil is scanned with both to show relative size.

Andrew Murphy, Shakespeare in Print (Cambridge UP, 2003)

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (9): the Hanmer edition of 1743-44

Lewis Theobald (1688-1744), a lawyer who enjoyed a limited success in the commercial theater, published a 194-page attack on Pope’s edition of Shakespeare in 1726.

Lewis Theobald (1688-1744), a lawyer who enjoyed a limited success in the commercial theater, published a 194-page attack on Pope’s edition of Shakespeare in 1726.

Like Pope, Theobald set out his editorial program in the Preface to his edition of Shakespeare, first published in 1733.

“Rowe had presented his readers with a clean page, containing his version of Shakespeare’s plays, formatted according to the conventions of the early eighteenth century and–in common with the seventeenth-century folios–lacking in annotation. Pope’s text was elegantly printed on the wider expanse of a quarto page, with generous margins . . . Theobald made a break with this general convention. In his edition, annotation became both more frequent and more intrusive on the page.”

Andrew Murphy, Shakespeare in Print (Cambridge UP, 2003)

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (8): Theobald’s 2nd edition of 1740

Unfortunately our copy of the Rowe edition is incomplete, and has been damaged by water.

Unfortunately our copy of the Rowe edition is incomplete, and has been damaged by water.

Nicholas Rowe (1674-1718) was a lawyer, playwright, and minor politician. In his editing of Shakespeare, Rowe essentially followed the Fourth Folio edition of 1685, although he claimed to have arrived at the text by comparing “the several editions.” He did, however, restore some passages in Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, Henry V, and King Lear from early texts.

In addition to being the first illustrated edition of Shakespeare’s collected works, this set marks the first octavo edition, the first to contain a biography of Shakespeare, and the first edition to bear an editor’s name. The seventh volume, produced by Edward Curll, contains poems. Rowe worked mainly from Fourth Folio. His contributions included lists of dramatis personae, act and scene divisions, and characters’ entrances and exits. His “Some Account of the Life, &c., of Mr. William Shakespear” served as the standard Shakespeare biography for the eighteenth century.

Andrew Murphy, Shakespeare in Print (Cambridge UP, 2003)

Andrew Murphy, Shakespeare in Print (Cambridge UP, 2003)

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (7): Rowe edition (1709)

Finally we come to our facsimile of the Fourth Folio, which was originally issued in 1685, when ownership of the plays had again changed hands:

Finally we come to our facsimile of the Fourth Folio, which was originally issued in 1685, when ownership of the plays had again changed hands:

“Eleanor Cotes’ rights passed to John Martin and Henry Herringman in August of 1674. Martin died in 1674 and his widow, Sarah, assigned his rights to Robert Scott (about whom little is known) in 1683. While Eleanor Cotes is known to have owned half the rights to the texts originally registered by Jaggard and Blount, it seems that Martin and Herringman believed that they had acquired these plays outright . . . In any event, by 1685 Henry Herringman was clearly the dominant rights-holder and his name appears as publisher on all of the title-pages of the Fourth Folio” [there are at least three states of the t.p.] . . .

“The Fourth Folio differs from the Second and Third in that it is not a page-for-page reprint of the 1623 original. The volume falls into three divisions, each with separate signatures and pagination: the Comedies; the Histories plus the Tragedies up to and including Romeo and Juliet; and the remainder of the Tragedies, together with the apocryphal plays added in 1664. The three sections are clearly the work of three distinct printshops.”

From Andrew Murphy, Shakespeare in Print (2003)

Comments Off on The Bard in the Watkinson (6): The Fourth Folio

In 1792 the comparatively unsuccessful Shakespearean Joseph Ritson had launched a direct assault on Edmund Malone’s 1790 edition, claiming that he wished “to rescue the language and sense” of Shakespeare “from the barbarism and corruption they have acquired in passing through the hands of this incompetent and unworthy editor,” and caricatured Malone as a “Paddy from Cork” Irishman.

In 1792 the comparatively unsuccessful Shakespearean Joseph Ritson had launched a direct assault on Edmund Malone’s 1790 edition, claiming that he wished “to rescue the language and sense” of Shakespeare “from the barbarism and corruption they have acquired in passing through the hands of this incompetent and unworthy editor,” and caricatured Malone as a “Paddy from Cork” Irishman.