“It is generally agreeable to be in the company of individuals who are naturally animated and pleasant. For this reason, nothing can be more gratifying than the society of Woodpeckers in the forests . . .

“It is generally agreeable to be in the company of individuals who are naturally animated and pleasant. For this reason, nothing can be more gratifying than the society of Woodpeckers in the forests . . .

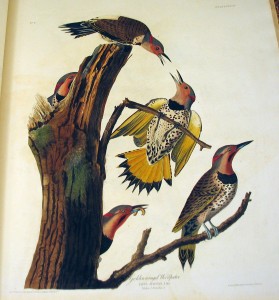

No sooner has spring called them to the pleasant duty of making love, as it is called, than their voice . . . is heard from the tops of high decayed trees, proclaiming with delight the opening of the welcome season. Their note at this period is merriment itself, as it imitates a prolonged and jovial laugh, heard at a considerable distance. Several males pursue a female, reach her, and, to prove the force and truth of their love, bow their heads, spread their tail[s], and move sideways, backwards and forwards, performing such antics, as might induce anyone witnessing them, if not of a most morose temper, to join his laugh to theirs. The female flies to another tree, where she is closely followed by one, two, or even half a dozen of these gay suitors, and where again the same ceremonies are gone through. No fightings occur, no jealousies seem to exist among these beaux, until a marked preference is shewn to some individual, when the rejected proceed in search of another female. In this manner all Golden-winged Woodpeckers are soon happily mated. Each pair immediately proceed to excavate the trunk of a tree, and finish a hole in it sufficient to contain themselves and their young. They both work with great industry and apparent pleasure. Should the male, for instance, be employed, the female is close to him, and congratulates him on the removal of every chip which his bill sends through the air. While he rests, he appears to be speaking to her on the most tender subjects, and when fatigued, is at once assisted by her. In this manner, by the alternate exertions of each, the hole is dug and finished. They caress each other on the branches, chase all their cousins the Red-heads, defy the Purple Grackles to enter their nest, feed plentifully on ants, beetles and larvae, cackling at intervals, and ere two weeks have elapsed, the female lays either four or six eggs, the whiteness and transparency of which are doubtless the delight of her heart . . .

Racoons and Black Snakes are dangerous enemies to this bird. The former frequently put one of their fore legs into the hole where it has nestled or retired to rest, and if the hole be not too deep, draw out the eggs and suck them, and frequently by the same means secure the bird itself. The Black Snake contents itself with the eggs or young. Several species of Hawk attack them on the wing, and as the Woodpeckers generally escape by making for a hole in the nearest tree, it is pleasing to see the disappointment of the Hawk, when, as it has just been on the point of seizing the terrified bird, the latter dives, as it were, into the hole.”

–J. J. Audubon, Ornithological Biography, I (1831), 191-194 [excerpted].