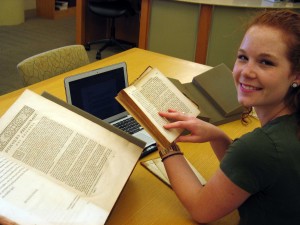

Julia Falkowski ’13, who was a Creative Fellow in the Watkinson in the Fall of 2012, and majored in English and American Studies, has won the New England American Studies Association‘s Lisa MacFarlane Prize for the year’s best undergraduate thesis. One of her faculty advisers cited her work with the Watkinson as being a key element in her approach to original sources.

Julia Falkowski ’13, who was a Creative Fellow in the Watkinson in the Fall of 2012, and majored in English and American Studies, has won the New England American Studies Association‘s Lisa MacFarlane Prize for the year’s best undergraduate thesis. One of her faculty advisers cited her work with the Watkinson as being a key element in her approach to original sources.Archive for September, 2013

We were swingin’

On September 20th we filled the Library atrium with music from the 1930s (played on a Victrola discovered in the Watkinson), cleared away the furniture and potted plants, and did a little swing dancing.

On September 20th we filled the Library atrium with music from the 1930s (played on a Victrola discovered in the Watkinson), cleared away the furniture and potted plants, and did a little swing dancing.

This was the official opening of our “Jump and Jive” exhibition, celebrating the gift of over 5,000 sound recordings constituting the Bennett “Bud” Rubenstein collection of jazz, pop, and big band music.

The event was attended by more than 40 people from the campus, Hartford, and New Britain, and included Barbara “Bert” Rubenstein (the donor, and widow of the collector), and one of her three daughters.

Mrs. Rubenstein shared reminiscences of the era and of her husband’s passion for the music–both in terms of collecting and playing it. They both went to many clubs in the 1940s where the likes of Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller were playing, so it was a special treat to have her here to see how the collection will be cared for and appreciated for generations to come.

Mrs. Rubenstein shared reminiscences of the era and of her husband’s passion for the music–both in terms of collecting and playing it. They both went to many clubs in the 1940s where the likes of Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller were playing, so it was a special treat to have her here to see how the collection will be cared for and appreciated for generations to come.

Members of the Hartford Underground (a local swing dance club) were on hand to show us some moves, and some of the students from Trinity’s own swing dance club (newly formed last year) joined in as well.

Members of the Hartford Underground (a local swing dance club) were on hand to show us some moves, and some of the students from Trinity’s own swing dance club (newly formed last year) joined in as well.

With the Rubenstein gift, the Watkinson now holds well over 10,000 sound recordings dating from the 1890s (wax cylinders) to the 1970s. The exhibition was curated by staffer Henry Arneth, who also serviced and repaired our Victrolas and gramophones so that we (and our patrons) can hear these recordings the way they were originally intended to be heard.

With the Rubenstein gift, the Watkinson now holds well over 10,000 sound recordings dating from the 1890s (wax cylinders) to the 1970s. The exhibition was curated by staffer Henry Arneth, who also serviced and repaired our Victrolas and gramophones so that we (and our patrons) can hear these recordings the way they were originally intended to be heard.

So the next time you pass our glass doors, don’t be surprised if you hear music and see us dancing!

Julia Falkowski ’13, who was a Creative Fellow in the Watkinson in the Fall of 2012, and majored in English and American Studies, has won the New England American Studies Association‘s Lisa MacFarlane Prize for the year’s best undergraduate thesis. One of her faculty advisers cited her work with the Watkinson as being a key element in her approach to original sources.

Julia Falkowski ’13, who was a Creative Fellow in the Watkinson in the Fall of 2012, and majored in English and American Studies, has won the New England American Studies Association‘s Lisa MacFarlane Prize for the year’s best undergraduate thesis. One of her faculty advisers cited her work with the Watkinson as being a key element in her approach to original sources.Early, scarce map of NYC

As a curator, keeping one eye on the rare book trade not only means that I see possible opportunities for acquisition–it also serves to focus attention on overlooked items. Here is my most recent “re-discovery.”

John Randel, The City of New York as laid out by the Commissioners with the Surrounding Countryside (New York, 1821).

A copy of this map recently came up for auction in New York, and although the one for sale was printed on satin (and is therefore much more valuable on the collector’s market), ours is still a scarce and important copy (one of only two or three known). We have contracted with a conservator to address some condition issues, to ensure this map can be used and displayed. Here are “before and after” pics–our conservator, Sarah Dove, worked miracles!

Here is excerpted text from the lot description (Swann Auction Galleries):

As New York City entered the 19th century, It became clear that plans for its expansion northward were in order. The narrow streets from the early Dutch and English settlers could no longer handle the increasing population. This was coupled with an increase in disease spawned by the close quarters of the city at that date.

In 1807 the Common Council of the city petitioned the State Legislature to create a Board of Commissioners to oversee the laying out of a future street system. The board was created and mandated to finalize its plans within a four year period. Governor Morris, Simeon de Witt, and John Rutherford became the commissioners. Simeon de Witt had been the Surveyor General for the state and had become impressed with the work of one of the surveyors under his charge, namely John Randel.

Randel was hired as chief engineer and surveyor for city. He began his work soon after. Though Manhattan Island was hardly a wilderness, it contained 60 miles of running streams, around 20 ponds and lakes, as well as hills, valleys and plateaus. With some surveying instruments of his own devise, Randel set to work. The difficulties of topography were not the only obstacles he was to encounter. Free-holders and lease-holders on the land being surveyed were fearful of losing their land and their rights. Randel was arrested a number of times for trespassing, and just as many times released on the order of the City Council.

Randel finished his project a bit ahead of schedule. The survey overlaid with the now famous grid street plan was ordered to be prepared for publication under the direction of William Bridges. Peter Maverick, the well known engraver, was chosen to engrave the map. The map map appeared in 1811 (Haskell 651) and is based almost entirely on the survey conducted by Randel, with some additions by Bridges. Randel’s name did not appear on the map. Thus began a long and acrimonious relationship between Randel and Bridges. Randel claimed that Bridges had not copied his survey faithfully and that it was full of errors. Randel took charge of the survey and embellished it further. He was set to have it published in 1814 but decided against it -the British had recently burned Washington and Randel feared his map would be too great an aid to the enemy should they decide to attack the city. The manuscript copy of the Randel embellishment is currently under the protection of the New York Historical Society.

In 1821 the finalized version of the map appeared under Randel’s name (his name appears 3 times on the map). The grid system begins with 1st street and runs northward to 155th street with the streets running from east to west. It is intersected by 12 avenues running from south to north. It is the grid which modern day inhabitants and the city’s many visitors have come to count on for easy navigation of the metropolis.

The Randel map was printed on paper and a very few seem to have been printed on satin. The only other existing copy on satin that we can locate is held by the New York Public Library, gifted by the well-known New York iconographer I. N. Phelps Stokes, who had acquired it from Randel’s nephew. Two paper copies are known.

In addition to the great importance this map bears in its relationship to the mapping of the city, it is a beautiful map to behold. In addition to the grid plan for New York City, there are incorporated maps of parts of Connecticut and Rhode Island as well as an inset of the city of Philadelphia. These are neatly overlaid on one another and with a trompe l’oeil effect they appear to roll in upon themselves.

For the fullest and most succinct history of the evolution of the map, Augustyn and Cohen’s Manhattan in Maps should be consulted.

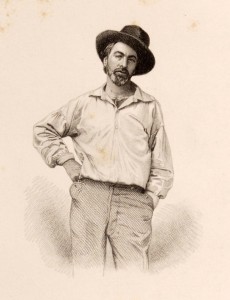

The Watkinson Library is seeking help from its friends and the alumni of Trinity College to acquire one of the great rarities of American literature–a first edition (1855) of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass.

The Watkinson Library is seeking help from its friends and the alumni of Trinity College to acquire one of the great rarities of American literature–a first edition (1855) of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass.

All donors who give $50.00 or more before December 31, 2013 will receive a letterpress printed broadside “honor roll” with his/her name under the following levels:

Versifier ($50-$99)

Rhymer ($100-$249)

Balladeer ($250-$499)

Poet ($500-$999)

Laureate ($1,000-$4,999)

Patron of Letters ($5,000+)

If you would like to contribute to this purchase, please contact Richard Ring, Head Curator & Librarian (richard.ring@trincoll.edu).

“Whitman paid out of his own pocket for the production of the first edition of his book and had only 795 copies printed, which he bound at various times as his finances permitted. Though critics and biographers have often speculated that the book appeared on the Fourth of July, thus serving as an appropriate marker of America’s literary independence, advertisements in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle make it clear that Leaves was actually issued in late June. His joy at getting the book published was quickly diminished by the death of his father a few weeks after the appearance of Leaves. Walter Sr. had been ill for several years, and though he and Walt had never been particularly close, they had only recently traveled together to West Hills, Long Island, to the old Whitman homestead where Walt was born. Now his father’s death along with his older brother Jesse’s absence as a merchant marine (and later Jesse’s growing violence and mental instability) meant that Walt would become the father-substitute for the family, the person his mother and siblings would turn to for help and guidance. He had already had some experience enacting that role even while Walter Sr. was alive; perhaps because of Walter Sr.’s drinking habits and growing general depression, young Walt had taken on a number of adult responsibilities—buying boots for his brothers, for instance, and holding the title to the family house as early as 1847. Now, however, he became the only person his mother and siblings could turn to.

But even given these growing family burdens, he managed to concentrate on his new book, and, just as he oversaw all the details of its composition and printing, so now did he supervise its distribution and try to control its reception. Even though Whitman claimed that the first edition sold out, the book in fact had very poor sales. He sent copies to a number of well-known writers (including John Greenleaf Whittier, who, legend has it, threw his copy in the fire), but only one responded, and that, fittingly, was Emerson, who recognized in Whitman’s work the very spirit and tone and style he had called for. “I greet you at the beginning of a great career,” Emerson wrote in his private letter to Whitman, noting that Leaves of Grass “meets the demand I am always making of what seemed the sterile and stingy nature, as if too much handiwork, or too much lymph in the temperament, were making our western wits fat and mean.” Whitman’s was poetry that would literally get the country in shape, Emerson believed, give it shape, and help work off its excess of aristocratic fat.

Whitman’s book was an extraordinary accomplishment: after trying for over a decade to address in journalism and fiction the social issues (such as education, temperance, slavery, prostitution, immigration, democratic representation) that challenged the new nation, Whitman now turned to an unprecedented form, a kind of experimental verse cast in unrhymed long lines with no identifiable meter, the voice an uncanny combination of oratory, journalism, and the Bible—haranguing, mundane, and prophetic—all in the service of identifying a new American democratic attitude, an absorptive and accepting voice that would catalog the diversity of the country and manage to hold it all in a vast, single, unified identity. “Do I contradict myself?” Whitman asked confidently toward the end of the long poem he would come to call “Song of Myself”: “Very well then . . . . I contradict myself; / I am large . . . . I contain multitudes.” This new voice spoke confidently of union at a time of incredible division and tension in the culture, and it spoke with the assurance of one for whom everything, no matter how degraded, could be celebrated as part of itself: ” What is commonest and cheapest and nearest and easiest is Me.” His work echoed with the lingo of the American urban working class and reached deep into the various corners of the roiling nineteenth-century culture, reverberating with the nation’s stormy politics, its motley music, its new technologies, its fascination with science, and its evolving pride in an American language that was forming as a tongue distinct from British English.

Though it was no secret who the author of Leaves of Grass was, the fact that Whitman did not put his name on the title page was an unconventional and suggestive act (his name would in fact not appear on a title page of Leaves until the 1876 “Author’s Edition” of the book, and then only when Whitman signed his name on the title page as each book was sold). The absence of a name indicated, perhaps, that the author of this book believed he spoke not for himself so much as for America. But opposite the title page was a portrait of Whitman, an engraving made from a daguerreotype that the photographer Gabriel Harrison had made during the summer of 1854. It has become the most famous frontispiece in literary history, showing Walt in workman’s clothes, shirt open, hat on and cocked to the side, standing insouciantly and fixing the reader with a challenging stare. It is a full-body pose that indicates Whitman’s re-calibration of the role of poet as the democratic spokesperson who no longer speaks only from the intellect and with the formality of tradition and education: the new poet pictured in Whitman’s book is a poet who speaks from and with the whole body and who writes outside, in Nature, not in the library. It was what Whitman called “al fresco” poetry, poetry written outside the walls, the bounds, of convention and tradition.”

From “Walt Whitman” by Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price

The Walt Whitman Archive http://whitmanarchive.org/biography/walt_whitman/index.html

ANNOUNCING OUR FALL 2013 CREATIVE FELLOWS!!

Christina Claxton ’16 was so excited to begin that she was working on her project even before classes started. Initially planning to do something with the French exploration of Canada (having spent 6 weeks at McGill University over the summer doing just that), she was distracted into another project focused on our fabulous first edition of Diderot’s L’Encyclopédie.

Christina Claxton ’16 was so excited to begin that she was working on her project even before classes started. Initially planning to do something with the French exploration of Canada (having spent 6 weeks at McGill University over the summer doing just that), she was distracted into another project focused on our fabulous first edition of Diderot’s L’Encyclopédie.

Christina has started recording her impressions on a blog titled Philologie de L’Encyclopédie, and says, “over the course of the semester, I will work with its volumes as well as related sources to understand both its impact on the time of its publication and how it has influenced present day knowledge and thinking.”

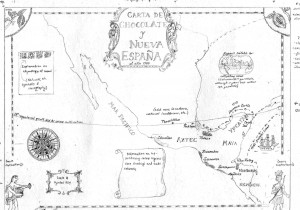

Maia Madison ’15 intrigued the committee by her desire to create hand-drawn maps tracing the spread of the use if cacao throughout the colonial Spanish Empire. Here is a further description of her ideas:

Maia Madison ’15 intrigued the committee by her desire to create hand-drawn maps tracing the spread of the use if cacao throughout the colonial Spanish Empire. Here is a further description of her ideas:

For those who wonder if she can pull this off, take a look at her “draft” sketch (her words) which I caught a look at in passing! If this is a quick sketch, imagine what the finished products will look like. Here is her plan, viz. the maps:

If this is a quick sketch, imagine what the finished products will look like. Here is her plan, viz. the maps:

Two 1-1/2’ x 2-1/2’ maps (one overall of New Spain, another zoomed in detail of Central America with inset on the layout of cacao orchards) with information on primary and secondary production regions, areas where flavoring agents were cultivated, trading routes, voyages, Spanish settlements, etc.

We look forward to seeing their projects unfold, and to announcing our Spring Fellows in December!

EXHIBITION OPENING of “Jump & Jive: Music from the 1920s, 30s, and 40s” on Friday, September 20th, 4:30-6:30pm!

EXHIBITION OPENING of “Jump & Jive: Music from the 1920s, 30s, and 40s” on Friday, September 20th, 4:30-6:30pm!

Come to the main library atrium and to the Watkinson to hear jazz and big band music playing on period Victrolas–just as it would have been heard in the Roaring 20s!

Between 5:30 and 6:30, swing dance instructor Javier Johnson and his partner My Janixia (from the Hartford Underground) will put on a dance display and teach a swing dance lesson to anyone brave enough to try!

We’ll have light refreshments in the Watkinson, and another Victrola playing music that will make your toes tap and your fingers snap!

Let’s make the library echo with rhythm and swing!