“In the spring of 1815, I for the first time saw a few individuals of this species at Henderson, on the banks of the Ohio, a hundred and twenty miles below the Falls of that river. It was an excessively cold morning, and nearly all were killed by the severity of the weather. I drew up a description at the time, naming the species Hirundo republicans, the Republican Swallow, in allusion to the mode in which the individuals belonging to it associate, for the purpose of forming their nests and rearing their young. Unfortunately, through the carelessness of my assistant, the specimens were lost, and I despaired for years of meeting with others.

“In the spring of 1815, I for the first time saw a few individuals of this species at Henderson, on the banks of the Ohio, a hundred and twenty miles below the Falls of that river. It was an excessively cold morning, and nearly all were killed by the severity of the weather. I drew up a description at the time, naming the species Hirundo republicans, the Republican Swallow, in allusion to the mode in which the individuals belonging to it associate, for the purpose of forming their nests and rearing their young. Unfortunately, through the carelessness of my assistant, the specimens were lost, and I despaired for years of meeting with others.

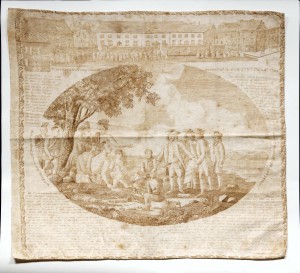

In the year 1819, my hopes were revived by Mr. ROBERT BEST, curator of the Western Museum at Cincinnati, who informed me that a strange species of bird had made its appearance in the neighbourhood, building nests in clusters, affixed to the walls. In consequence of this information, I immediately crossed the Ohio to Newport, in Kentucky, where he had seen many nests the preceding season; and no sooner were we landed than the chirruping of my long-lost little strangers saluted my ear. Numbers of them were busily engaged in repairing the damage done to their nests by the storms of the preceding winter.

Major OLDHAM of the United States Army, then commandant of the garrison, politely offered us the means of examining the settlement of these birds, attached to the walls of the building under his charge. He informed us, that, in 1815, he first saw a few of them working against the wall of the house, immediately under the eaves and cornice; that their work was carried on rapidly and peaceably, and that as soon as the young were able to travel, they all departed. Since that period, they had returned every spring, and then amounted to several hundreds. They usually appeared about the 10th of April, and immediately began their work, which was at that moment, it being then the 20th of that month, going on in a regular manner, against the walls of the arsenal. They had about fifty nests quite finished, and others in progress.”

–J. J. Audubon, Ornithological Biography, I (1831), 353 [excerpted].