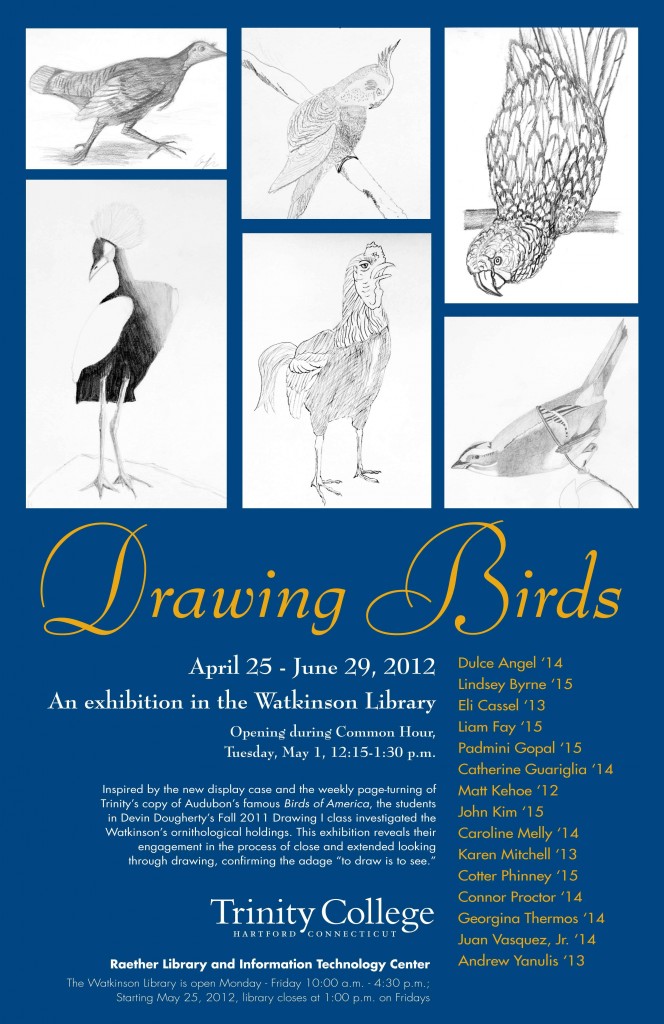

“This little bird so much resembles the young of that called, I know not why, the Blue-eyed Yellow Warbler, that I was at first inclined to think it the same; but, recollecting that the latter acquires the full colouring of its plumage, in both sexes, before the return of spring, and finding some material differences in their habits, I have not hesitated in presenting it to you, kind reader, not only as a new species, but as one extremely rare in the United States.

“This little bird so much resembles the young of that called, I know not why, the Blue-eyed Yellow Warbler, that I was at first inclined to think it the same; but, recollecting that the latter acquires the full colouring of its plumage, in both sexes, before the return of spring, and finding some material differences in their habits, I have not hesitated in presenting it to you, kind reader, not only as a new species, but as one extremely rare in the United States.

I shot two of these birds in May 1821, near the town of Jackson, in the state of Louisiana. They were sitting amongst the stalks of the plant, on which they are represented . . . I shot both the parents, and took the young under my care, but they would not receive any food, and died towards the end of the second day after their removal. I have never seen another of these birds since.

. . . The plant is known by the name of the Wild Spanish Coffee. It grows very abundantly in almost every field in the Uplands of Lower Louisiana. The smell of its flowers, as well as of its leaves, is extremely disagreeable, if not nauseous.”

–J. J. Audubon, Ornithological Biography, I (1831), 180 [excerpted].