Remembering Fred Pfeil

Last night we had a very successful event in the Watkinson for the students of the “Fred.” This is how they describe themselves:

Last night we had a very successful event in the Watkinson for the students of the “Fred.” This is how they describe themselves:

“Begun at the start of the 2006-2007 academic year, the Fred Pfeil Community Project is a student-run campus living alternative named after beloved Professor of English, Fred Pfeil, who died of cancer in December 2005. The purpose of The Fred is to create a comfortable and vibrant space for all students to unite social, cultural, and intellectual interests, thereby enriching campus life. ”

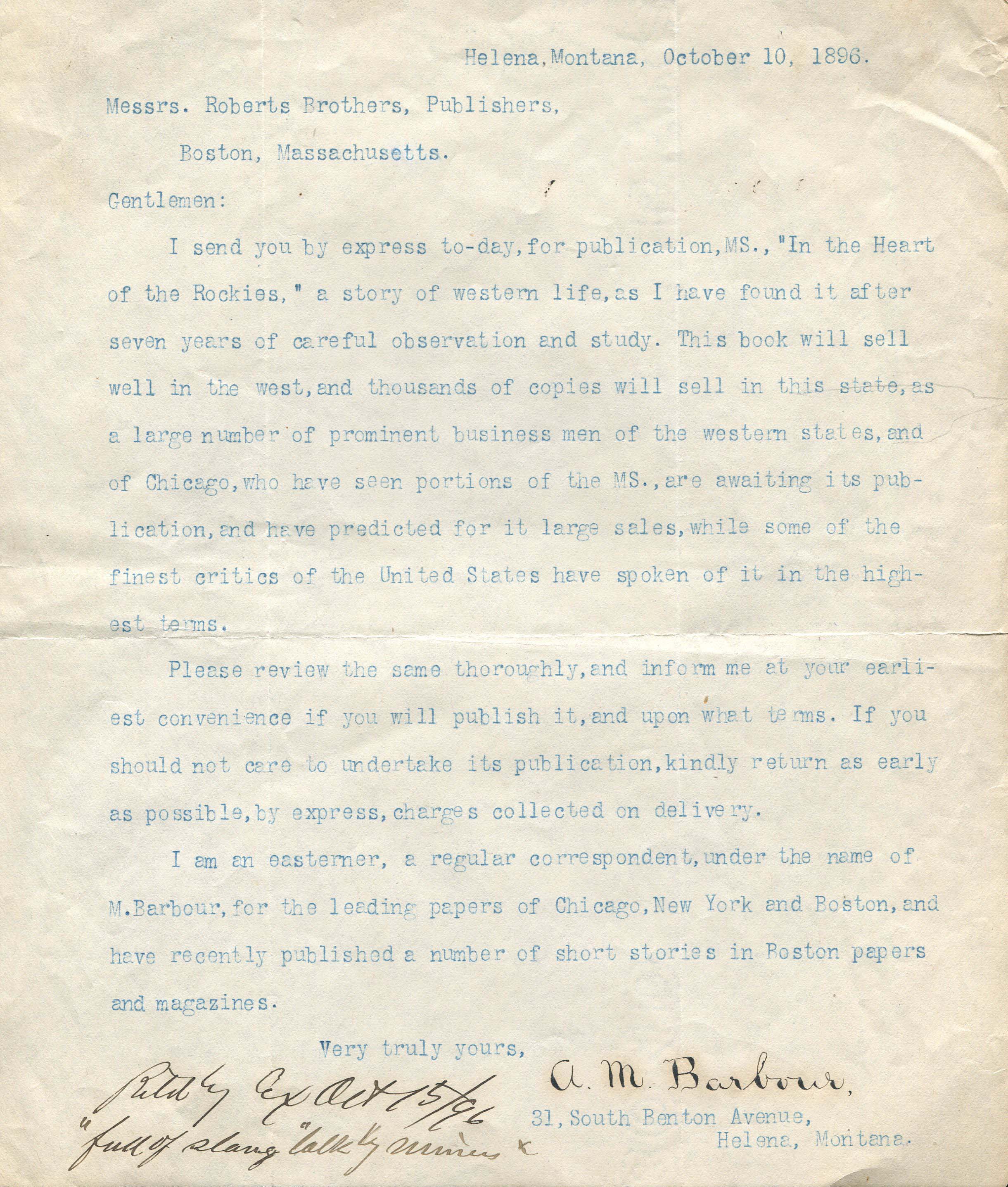

We invited these students, none of whom had ever met Fred Pfeil, to come and hear his colleagues and friends share memories and read a few poems, to give the students a sense of the man. We produced a keepsake with three of these memories, which I include below for those who could not attend. The pic shown is of all of the Fred students (past, present, future) around Elli Findly, Fred Pfeil’s widow. About 60 people attended all told, and we are planning to make this an annual event on social justice and/or activism, in partnership with the fred.

Memories:

For ten years I knew Fred and marveled at his genuine love for improving himself by helping others. I spent many weekends with Fred at Enfield Correctional Facility where we ran workshops on Alternatives to Violence. It was there that I saw how fulfilling and inspiring it could be to work selflessly helping others. I engaged in this work when I could; Fred made this his life’s work. And it was through such work that Fred’s life intersected with so many others, and through his example others like me became involved as well.

What would strike anyone who came to know Fred was his great joy about every day and about interacting with whomever he was with in a very personal and joyful manner. Fred was fun. He had a lot of fun and he was great fun to be around. It was great fun just to ruminate about life with him because he was so thoughtful and insightful about so many things. He made social activism fun, and he was a living example of how fulfilling life could be when lived with a greater purpose in mind. I have known very few people personally who could inspire me to live a better life, and Fred remains the greatest example for me in this regard.

He was a great friend to so many people, and everyone one of them I think thought of themselves as a special friend to him. Fred had the unique ability to make a very great number of people feel that they had a special relationship and friendship with him. I remain amazed at the number of people whose lives Fred touched and who he inspired through friendship and example.

Fred’s death left a great hole in the lives of his many friends and colleagues. All of us who knew Fred are poorer for his absence. But in important ways I always feel Fred’s presence, mainly because it’s so hard to believe that someone who was so alive and so present in my life is now gone. And so on occasion I find myself having silent conversations with him despite his absence. I can easily hear his voice and I know what’d he say about certain things that I’d ask him. And I can only hope that I remain inspired by Fred to live that better and fuller life that he sought not just for himself but for everyone around him.

—Brian Waddell

Of all my memories of Fred, and particularly of those that focus on his social activism and concern for human rights and welfare, the one that stands out is the most personal. In 2004, my son Luke was in the throes of a teenage rebellion that manifested primarily as narcissism and hostility against me, his single parent. At first I found it strange that of all my friends and colleagues, Fred was the easiest person to talk to about my dilemma—after all, he had no children of his own and could never be a mother. But it was Fred’s wont to listen with his whole attention and then to search for how he might help with any situation. Not for him was the idle sympathy of “How hard that must be for you.” He was a person of empathy and action.

Fred and I took a long drive to the Berkshires that spring, to meet with other members of the writing group that Fred had assembled, at Dori Katz’s house in Stockbridge. On the way back to Hartford, I was speaking with him about Luke and he held up a finger. “I have an idea,” he said. He told me about a group of young men he was mentoring—I no longer remember the name of the organization—in downtown Hartford. These were hardened young guys who had been in juvie or were on probation and who were gathering in a circle to come to honest grips with their lives over an intense weekend.

At first I misunderstood Fred. I thought he was suggesting that Luke join this group of guys who’d been in trouble with the law, and I foresaw the outrage of my bratty teenager when he found himself labeled a juvenile delinquent. But as I started to object, Fred clarified his idea. He wanted Luke to come down to Wethersfield Avenue and help. He wanted him to be a peer mentor for the group. Luke would have to commit to the whole weekend. But Fred would help train him so that he could engage with the troubled young men in an effective way.

“But you don’t even know Luke,” I objected. Wasn’t it enough that Fred was giving of his own time and energies to help these guys? Did he really want to put his therapeutic structure at risk by bringing in my kid, who wasn’t exactly a model of stability, to “mentor” anyone?

Not to worry, Fred said, smiling. Just so long as Luke was willing to commit to the whole weekend. He was sure Luke could be very helpful. And maybe it would help Luke.

To be blunt, I thought it was a crazy idea. But I agreed to propose it to my teenaged rebel. Luke had met Fred once, I think, at Fred and Elli’s housewarming, and had respect for him. “Just call him,” I said to Luke when I got home from the Berkshires. “He’ll explain.”

Luke called Fred. He met with him. That weekend, for the first time in months, Luke was up before 8:00 a.m., and pestering me to get him down to Wethersfield Avenue on time, because he needed to help Fred, and Fred was counting on him.

I don’t know what went on in those counseling sessions. I know that Luke came home a little wide-eyed at the stories he had heard. But he also came home walking a little taller, with a sense of purpose that I had not seen in him before. He was less quick to flare up, more aware of others around him.

It was not, Fred insisted, a big deal. No, it wasn’t. And it wasn’t as if a weekend on Wethersfield Avenue solved my son’s issues. But what remains remarkable to me, after all these years, is how Fred knew, instinctively, exactly what he could offer that would be truly useful. He wasted no words, or time, on making himself feel generous, nor did he change his original goal with the young men downtown. He simply, on faith, picked Luke up and brought him along on the mission, knowing that the healthiest way to be in the world is to be engaged with others in the world, especially others who need you. That you find your strength, as you find your generosity, in using it. That’s a lesson Luke learned from Fred, and I—since, after all, the favor was for me—will keep dear to my heart.

—Lucy Ferriss

As one who was privileged to chair both the Department and the Committee that hired Fred Pfeil, I have stories that go back to that moment when Fred agreed to trade his beloved Oregon for Connecticut. I could, then, talk about the way he balanced literary criticism and theory with writing novels, a delicate juggling act; or how he managed to merge an extraordinary commitment to political activism not only with his own intensely private meditative life but also with mentoring and teaching meditative mantras, moving between protest-peopled streets and Buddhist hermit cells, with a full life in between. Indeed, he was scheduled to teach a meditation class on the night he died.

I could reflect on the ways in which he engaged students in his own activism – on behalf of Trinity’s food staff in their drive for equality or working for urgent causes further from home. Or on his inimitable style, commemorated in the annual “Fred Pfeil proletariat dress award” that, with tongues in cheek, we in the English Department used to give a graduating senior each year. Or marvel at how Fred sustained his proletariat sympathies while retaining the admiration, respect, and affection not only of his students, colleagues and friends, but even of the administration whose policies he sometimes called into question. Around us, the voices that rise in protest against the kinds of injustices that plagued Fred have often, in the terms of the poet W. B. Yeats, “grown shrill.” But though he protested fiercely, often taking students to march with him, and even organizing a few on the Trinity campus, Fred’s voice was never shrill. He reveled in life, and never lost either his sense of joy or his courtesy, even as he fought for those who had been dealt the lesser hands in the game he so loved. And he was, in turn, respected and revered often by those he criticized! A rare achievement.

Speaking of administrators he did not alienate, Fred started Film Studies at Trinity with one of those administrators, a former English Department colleague, interim President of Trinity, and now President of the University of Puget Sound, Ron Thomas, and an equally good friend Professor Arthur Feinsod, now director of Theater at Indiana State University. Knowing how important film was to Fred, I could, then, focus on my own commitment to sustaining and developing Film Studies at Trinity, my perpetual gift to Fred.

There are many stories from the too few years we shared with him. But I have chosen to focus on the last few days of Fred’s life, when his friends and colleagues held our vigil in the hospice care wing of Hartford Hospital. For five long days, we waited and watched: laughing, mourning, celebrating, sometimes sharing food while Fred held court in his room, meeting us one at a time for an audience fit for the regal presence he brought to those special, final days. The Pope himself could not have offered a more gracious presence. With each of us he talked – about literature, about life, with an eye for planning for the future that he, as well as we, knew would not be his. When reading poetry together with me – the poem of Gwendolyn Brooks that I would ultimately read at his Memorial service – he told me with a fond sense of expectation that he hoped he would be able to meet Brooks (who survived him by a mere five years) again in his lifetime, and he meant it. When I told him admiringly that he had read more than anyone else I had ever met, he thoughtfully replied: “Well, there is always David Rosen,” a tribute from one unbelievable reader to another that I have often shared with David himself.

Most of all perhaps, I remember the birthday party he threw in his hospice room for Elli, whom he called his “sweetie,” on her birthday, November 26, the last Saturday of his life. Having managed to hang on through Thanksgiving, he had one more important date to keep, and he put an entire lifetime of reserved energy into making the last birthday Elli would share with him into a momentous occasion. As he arranged for food to be brought in and to surprise her with a cake, friends, and presents, he told all who would listen how special it was to have shared his life with the woman who was his love, his partner, his fellow in meditation, and in the most basic sense, his soulmate, the most beautiful woman he had ever met. Once that party was over – and it was the only time I recall that there was more than one of us at a time allowed into his room – Fred had made his peace. He was ready to let go, and he did. He had told Elli that he had reached the querencia, the place in the bullring where facing his inevitable death the bull feels most comfortable. Fred was there, in that protected magical circle – alive, vital, reaching out, but instead of attacking or defending himself, he spent his last days trying to make US comfortable, to help us share that space of recognition and acceptance with him.

I last saw him, just about an hour before he died on Tuesday afternoon, November 29, 2005, with Nick Davis, our first fulltime Film Studies professor, hired to replace Fred who was to take a two year stint in the Tutorial College, who was there to replace him as he moved into his more permanent leave. As Nick and I stood beside our friend, it was obvious to both of us that without words, or even apparent recognition, Fred imperceptibly acknowledged us. And so, instead of saying good-by, Nick told him about the film he would be screening that night, and I too shared stories of things to come, not things gone by.

Fred’s voice has now been added to the Song of the Universe that he so loved. I believe he is present with us today as he will always be in the spirit of The Fred, in Film Studies, in the heart of his “Sweetie,” and in the broader universal kinship that he shared with all he knew, and that he still shares with us.

So may I once more say simply: “Good night, Sweet Prince.”

—Milla Cozart Riggio

Tags: Events