On December 7th we hosted a History Day seminar for eighteen 8th-graders from Renzulli Academy in Hartford. The theme this year for History Day in Connecticut is “Revolution, Reaction, Reform in History.” In the first part of the workshop I brought out one (1) primary resource held by the Watkinson related to the following revolutions in history:

On December 7th we hosted a History Day seminar for eighteen 8th-graders from Renzulli Academy in Hartford. The theme this year for History Day in Connecticut is “Revolution, Reaction, Reform in History.” In the first part of the workshop I brought out one (1) primary resource held by the Watkinson related to the following revolutions in history:

The Glorious Revolution (1688)

A 1689 pamphlet attributed to Daniel Defoe titled Reflections upon the late great revolution, about the Glorious Revolution (1688), when James II of England was overthrown by William of Orange (backed by a Dutch fleet), who becomes William II of England; James was tolerant of Catholics (which was unpopular) and had just had a son, which disrupted the line of succession (William’s wife Mary, a Protestant, had been the heir presumptive). The new heir threatened England with a Catholic dynasty. Members of the opposition in Parliament invited William to invade, and with that support the revolution was won with only a few minor battles and little bloodshed.

Issue 2 of Thomas Paine’s The American Crisis (1776), one of a series of pamphlets published from 1776 to 1783 during the American Revolution. The first part was written during Washington’s retreat across the Delaware and by his order was read to his dispirited and suffering soldiers. The opening sentence was adopted as the watchword of the movement to Trenton: “These are the times that try men’s souls: The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it NOW, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.”

(French Revolution, 1789)

Historical and critical memoirs of the general revolution in France by an Irish nobleman (Sir John Talbot Dillon), published in 1790, is interesting not only as a collection of original documents, but as giving the views of a contemporary while the revolution was yet in its first stage. Dillon was an ardent advocate of religious liberty, and an uncompromising enemy of intolerance in every shape. He was a firm believer in the moderation of the revolution. With all his enthusiasm for liberty, however, he was not disposed to extend it to African slaves in the West Indies. ‘God forbid,’ he says, ‘I should be an advocate for slavery as a system;’ but in their particular case he regarded it as a necessary evil, and believed that upon the whole they were far better off as slaves than they would be if set free.

Historical and critical memoirs of the general revolution in France by an Irish nobleman (Sir John Talbot Dillon), published in 1790, is interesting not only as a collection of original documents, but as giving the views of a contemporary while the revolution was yet in its first stage. Dillon was an ardent advocate of religious liberty, and an uncompromising enemy of intolerance in every shape. He was a firm believer in the moderation of the revolution. With all his enthusiasm for liberty, however, he was not disposed to extend it to African slaves in the West Indies. ‘God forbid,’ he says, ‘I should be an advocate for slavery as a system;’ but in their particular case he regarded it as a necessary evil, and believed that upon the whole they were far better off as slaves than they would be if set free.

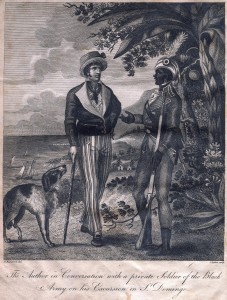

For this I showed Marcus Rainsford’s 1805 An historical account of the black empire of Hayti, a famous source. The slaves in the French colony of St. Domingue (now known as Haiti) staged a revolt and declared independence from France. Other than the American Revolution, this was the only rebellion that successfully created a new government in the Western Hemisphere during the eighteenth-century. In 1789 St. Domingue produced 60 percent of the world’s coffee and 40 percent of the world’s sugar imported by France and Britain. The colony was the most profitable possession of the French Empire, but enslaved blacks outnumbered whites and free people of color ten to one.

(The Mexican War of Independence, 1810-21)

What started as an idealistic peasants’ rebellion against their colonial masters ended as an unlikely alliance between Mexican ex-royalists and Mexican guerrilla insurgents. The source for this was William David Robinson’s very popular Memoirs of the Mexican Revolution (1820).

(The Easter Rising, Ireland, 1916)

(The Easter Rising, Ireland, 1916)

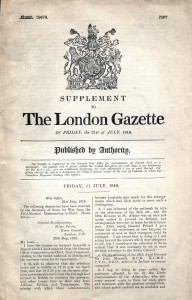

For this I showed a 1916 “extra” issue of the London Times, detailing the British response. An insurrection staged in Ireland during Easter Week, 1916, the Rising was mounted by Irish republicans with the aims of ending British rule in Ireland and establishing the Irish Republic at a time when the British Empire was heavily engaged in the First World War. It was the most significant uprising in Ireland since the rebellion of 1798, and led to the Irish War of Independence, and the formation of the Irish Republic in 1921.

In the second part of the workshop I had the students look at scans from an 1811 textbook on geography, a book which students their age would have used in school 200 years ago in Connecticut. The sections on meteorology and science were particularly interesting to the kids.