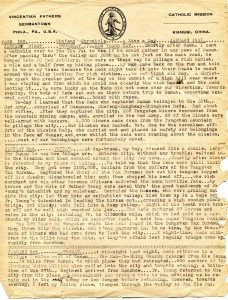

We recently received a gift from a resident of Cromwell, CT a series of typed daily accounts which amount to a diary by William J. McClimont, a Catholic missionary in China in 1931. Entries are often addressed to his “aunt Sadie” (F. Sadie Briggs, of Philadelphia). It is 417 typed, single-spaced pages, and starts on page 159 (see the entry for January 4, shown here, where he explains that a part of the diary was burned. The surviving pages begin with January 1, 1931, and it is complete for every day of the year to December 31, ending on Page 576. There are often manuscript additions on the pages, or on the versos–mostly polite inquiries into the health of family members, but often other notes as well. He also seems to be excerpting from other sources as well as adding his own bits.

We recently received a gift from a resident of Cromwell, CT a series of typed daily accounts which amount to a diary by William J. McClimont, a Catholic missionary in China in 1931. Entries are often addressed to his “aunt Sadie” (F. Sadie Briggs, of Philadelphia). It is 417 typed, single-spaced pages, and starts on page 159 (see the entry for January 4, shown here, where he explains that a part of the diary was burned. The surviving pages begin with January 1, 1931, and it is complete for every day of the year to December 31, ending on Page 576. There are often manuscript additions on the pages, or on the versos–mostly polite inquiries into the health of family members, but often other notes as well. He also seems to be excerpting from other sources as well as adding his own bits.

According to A Dictionary of Asian Christianity (2001), in the article on “China,” p. 144: “…The chaotic situation [of the Anti-Christian movement, begun in the early 1920s] was brought under control when the Northern Expedition was concluded and the government, under the leadership of the Nationalist Party, expelled the Communists from its camp. Social order was restored and religious freedom was re-ensured. Missionaries were able to return to their stations, but the number was reduced due to severe budget cuts for mission work owing to the Great Depression beginning in 1929. After Jiang Jiashi (Chiang Kai-shek) became a Christian [he was baptized Methodist in 1929], the church-state relationship warmed up significantly. Christians were invited to play a role in the social and cultural reconstruction programs conducted by the Nationalist Government (“New Life Movement”) in the 1930s.”

There are at least two archival collections that relate to this diary, a major collection at DePaul University and a few records at the New York State Library.

There is also a 1951 MA thesis (Catholic U.) by Julius Schick, Diplomatic Correspondence concerning the Chinese missions of the American Vincentians, 1929-1934.

Comments Off on Letters home from a Catholic missionary in China, 1931

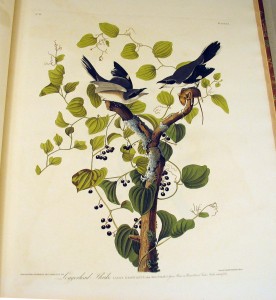

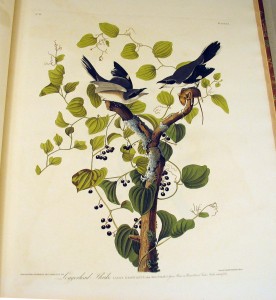

In Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas, “it is seen along the fences and bushes about the rice plantations, at all seasons, and is of some service to the planter, as it destroys the field-mice in great numbers, as well as many of the larger kinds of grubs and insects, upon which it pounces in the manner of a hawk.

In Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas, “it is seen along the fences and bushes about the rice plantations, at all seasons, and is of some service to the planter, as it destroys the field-mice in great numbers, as well as many of the larger kinds of grubs and insects, upon which it pounces in the manner of a hawk.

The Loggerhead has no song, but utters a shrill clear creaking prolonged note, resembling the grating of a rusty hinge slowly moved to and fro . . . The male courts the female without much regard, and she, in return, appears to receive his haughty attentions with merely just as much condescension as enables her to become the mother of a family, whose feelings are destined to be of the same cold nature.”

–J. J. Audubon, Ornithological Biography, I (1831), 300 [excerpted].

Comments Off on The Loggerhead Shrike (Audubon “bird of the week”)

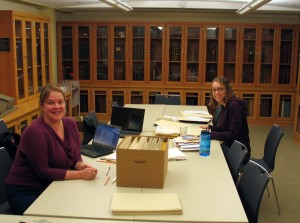

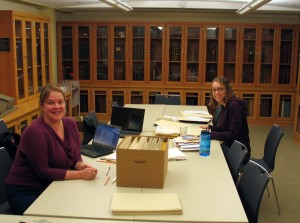

This is the sort of use we aim for in the Watkinson!

Today in the Enders seminar room, graduate student Meg Campbell is processing the Cinestudio archives, and contract archivist Rachel Hoff is processing a small collection of records related to Trinity’s development of the Learning Corridor.

Today in the Enders seminar room, graduate student Meg Campbell is processing the Cinestudio archives, and contract archivist Rachel Hoff is processing a small collection of records related to Trinity’s development of the Learning Corridor.

Occupying one half of the Reading Room, 1/2 of Kathleen Curran’s Art History class (19thC architecture) is examining books from our collection of the professional library of architect J. Cleveland Cady (1837-1919).

Occupying one half of the Reading Room, 1/2 of Kathleen Curran’s Art History class (19thC architecture) is examining books from our collection of the professional library of architect J. Cleveland Cady (1837-1919).

And in our exhibition area, archivist Peter Knapp holds forth to the OTHER 1/2 of the class on the concept drawings done by William Burges for the Long Walk done in the 1870s.

After half an hour, the class switches, and so they get two presentations for the price of one!

Comments Off on Yep–we’re busy!

“The interior of woods seems, as I have said, the fittest haunts for the Red-shouldered Hawk. He sails through them a few yards above the ground, and suddenly alights on the low branch of a tree, or the top of a dead stump, from which he silently watches, in an erect posture, for the appearance of squirrels, upon which he pounces directly and kills them in an instant, afterwards devouring them on the ground. If accidentally discovered, he essays to remove the squirrel, but finding this difficult, he drags it partly through the air and partly along the ground, to some short distance, until he conceives himself out of sight of the intruder, when he again commences feeding. The eating of a whole squirrel, which this bird often devours at one meal, so gorges it, that I have seen it in this state almost unable to fly, and with such an extraordinary protuberance on its breast as seemed very unnatural, and very injurious to the beauty of form which the bird usually displays.”

“The interior of woods seems, as I have said, the fittest haunts for the Red-shouldered Hawk. He sails through them a few yards above the ground, and suddenly alights on the low branch of a tree, or the top of a dead stump, from which he silently watches, in an erect posture, for the appearance of squirrels, upon which he pounces directly and kills them in an instant, afterwards devouring them on the ground. If accidentally discovered, he essays to remove the squirrel, but finding this difficult, he drags it partly through the air and partly along the ground, to some short distance, until he conceives himself out of sight of the intruder, when he again commences feeding. The eating of a whole squirrel, which this bird often devours at one meal, so gorges it, that I have seen it in this state almost unable to fly, and with such an extraordinary protuberance on its breast as seemed very unnatural, and very injurious to the beauty of form which the bird usually displays.”

–J. J. Audubon, Ornithological Biography, I (1831), 297 [excerpted].

Comments Off on Red-shouldered Hawk (Audubon “bird of the week”)

“I have named this pretty and rare species after Baron Cuvier, not merely by way of acknowledgement for the kind attentions which I have received at the hands of that deservedly celebrated naturalist, but more as a homage due by every student of nature to one at present unrivalled in the knowledge of General Zoology.

“I have named this pretty and rare species after Baron Cuvier, not merely by way of acknowledgement for the kind attentions which I have received at the hands of that deservedly celebrated naturalist, but more as a homage due by every student of nature to one at present unrivalled in the knowledge of General Zoology.

I shot the bird represented in the Plate, on my father-in-law’s plantation of Flatland Ford, on the Skuylkill River in Pennsylvania, on the 8th June, 1812, while on a visit to my honored relative Mr. William Bakewell . . . I have not seen another since, nor have I been able to learn that this species has been observed by any other individual.”

–J. J. Audubon, Ornithological Biography, I (1831), 288 [excerpted].

Comments Off on Cuvier’s Regulus (Audubon “Bird of the Week”)

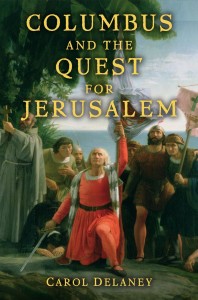

A public talk and book signing by the author

Wednesday, November 7, 3:00pm

The Watkinson Library

By situating Columbus in the cultural context of his times, my talk discusses the little known reasons behind his voyages. He did not set out to prove the earth was round (most of his contemporaries already knew that), nor did he expect to discover a new world. In a number of extant writings, he clearly stated the ultimate purpose of his voyages: to sail to Asia to obtain gold through trade with the Grand Khan of Cathay in order to finance a crusade to wrest Jerusalem from the Muslims. This was a necessary precondition for Christ’s return before the end of the world. Columbus, like many of his contemporaries, keenly felt that the end was imminent, and he was prepared to play his part in the unfolding apocalyptic drama. Because the religious ideas that motivated Columbus have resurfaced in a very different and more dangerous world, I believe his story can be read as a parable for our times.

Dr. Carol Delaney is Emerita Professor, Cultural and Social Anthropology at Stanford University & an Invited Scholar at the John Carter Brown Library, Brown University.

Comments Off on The Holy Quest of Columbus

“[In Louisiana] they pass under the name of Meadow Birds. In Pennsylvania they are called Reed Birds, in Carolina Rice Buntings, and in the Sate of New York Boblinks. The latter appellation is given to them as far eastward as they are known to proceed for the purpose of breeding . . .

“[In Louisiana] they pass under the name of Meadow Birds. In Pennsylvania they are called Reed Birds, in Carolina Rice Buntings, and in the Sate of New York Boblinks. The latter appellation is given to them as far eastward as they are known to proceed for the purpose of breeding . . .

About the middle of May . . . they have become so plentiful, and have so dispersed all over the country, that it is impossible to see a meadow or a field of corn, which does not contain several pairs of them. The beauty, or, perhaps more properly, the variety of their plumage, as well as of their song, attracts the attention of the bird-catchers. Great numbers are captured and exposed for sale in the markets, particularly in those of the city of New York. They are caught in trap-cages, and feed and sing almost immediately after. Many are carried to Europe, where the shipper is often disappointed in his profits, as by the time they reach there, the birds havbe changed their colours and seem all females . . .

No sooner have the young left the nest, than they and their parents associate with other families, so that by the end of July large flocks begin to appear . . . Now begin their devastations. They plunder every field, but are shot in immense numbers”

–J. J. Audubon, Ornithological Biography, I (1831), 283-285 [excerpted].

Comments Off on The Rice Bird (Audubon “bird of the week”)

In Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas, “it is seen along the fences and bushes about the rice plantations, at all seasons, and is of some service to the planter, as it destroys the field-mice in great numbers, as well as many of the larger kinds of grubs and insects, upon which it pounces in the manner of a hawk.

In Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas, “it is seen along the fences and bushes about the rice plantations, at all seasons, and is of some service to the planter, as it destroys the field-mice in great numbers, as well as many of the larger kinds of grubs and insects, upon which it pounces in the manner of a hawk.