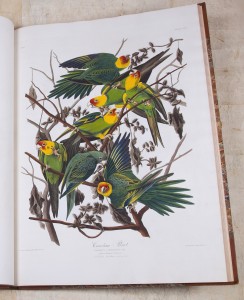

“This, reader, is one of the scarce birds that visit the United States from the south, and I have much pleasure in being able to give you an account of it, as hitherto little or nothing has been known of its history.

“This, reader, is one of the scarce birds that visit the United States from the south, and I have much pleasure in being able to give you an account of it, as hitherto little or nothing has been known of its history.

It is an inhabitant of Louisiana during the spring and summer months, when it resorts to the thick cane-breaks of the alluvial lands near the Mississippi, and the borders of the numberless swamps that lie in a direction parallel to that river . . . In the month of May 1809, I killed a male and a female of this species, near the mouth of the Ohio, while on a shooting expedition after young swans. The following spring, I killed a female near Henderson in Kentucky. In 1821, I again procured a pair, with their nest and eggs, near the mouth of the Bayou La Fourche, on the Mississippi, and since that period have killed eight or ten pairs . . .

The manners of this bird are not those of the Titmouse, Fly-catcher, or Warbler, but partake of those of all three. It has the want of shyness exhibited in the Red-eyed and Yellow-throated Fly-catchers. It hangs to bunches of small berries, feeding upon them as a Titmouse does on buds of trees; and again searches among the leaves and along the twigs of low bushes, like most of the Warblers. On the other hand, it differs from all these in their principal habits. Thus, it never snaps at insects on the wing, although it pursues them; it never attacks small birds and kills them by breaking in their skulls, as the Titmouse does; nor does it hold its prey under its foot in the way of the Yellow-throated Fly-catcher or Vireo, a habit which allies the latter to the Shrikes . . . I have never heard it utter a note beyond that of a querulous low murmuring sound, when chasing another bird from the vicinity of its nest.”

–J. J. Audubon, Ornithological Biography, I (1831), 147-148 [excerpted].